No 70

A Friend of a Lifetime:

On Yu Boya smashes his zither to mourn a dear friend, a youth book

What is friendship at its depths, and who is a true friend? When one has found the friend of a lifetime, how is one to confront the inevitable parting which comes at the end of the mortal life? These are questions which a young man from early 19th century Beijing, inspired by a tale of two friends from Chinese antiquity, came to ruminate on in a special copy he made of a book he bought, Yu Boya smashes his zither to mourn a dear friend. What was the story he read, and how did it come to touch his heart? What can the manuscript, sprinkled with his notes and commentaries, tell us today about his world as a reader?

The manuscript, held at the Capital Library of China, belonged formerly to Wu Xiaoling (1914-1995), a major scholar and collector of Chinese vernacular literature, who had acquired it from his middle school teacher Zheng Qian. The slim volume of 43 folios, measuring 12.6 cm by 26.9 cm, has lost its original cover and binding; later preservation has given it its present appearance, with four-hole thread binding and backing applied to the folios. The manuscript contains the earliest dated handwritten text of zidishu (interpreted variously as “youth book,” “scions’ tale,” or “bannermen tale”). This was a genre of verse narrative which once flourished in north China as a form of performing art between the mid-18th and the end of the 19th centuries, with verse in seven-syllable lines sung to the accompaniment of the three-stringed lute. Our manuscript reveals that zidishu were once also the object of serious reading, and provides important clues into their early community of readers.

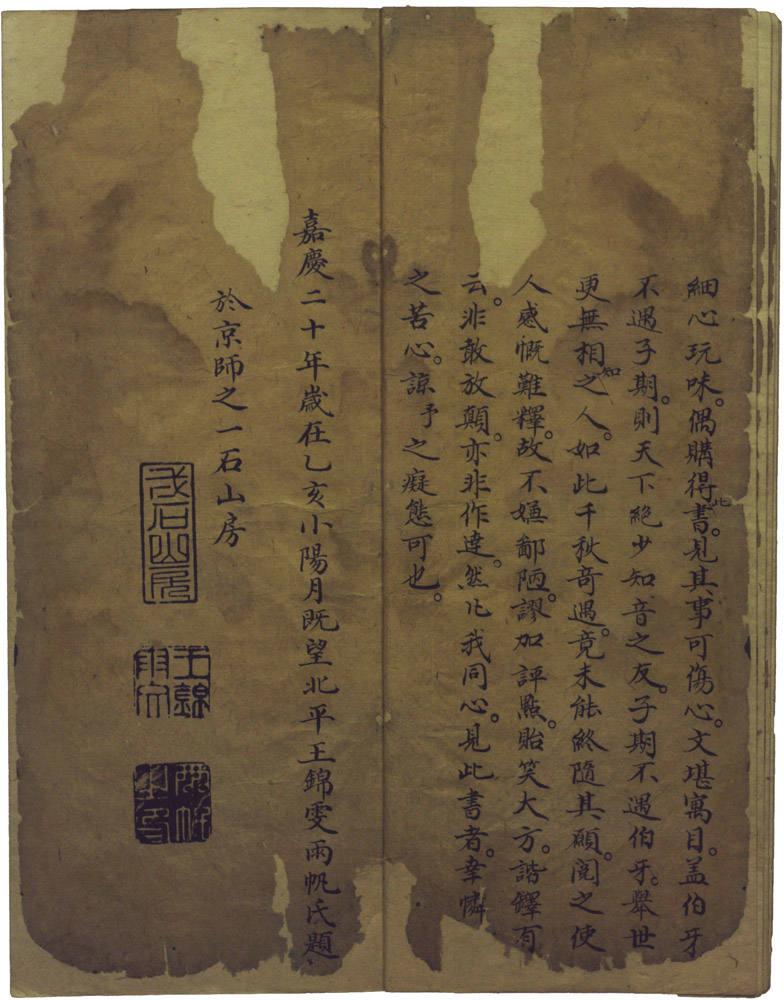

The neatly prepared manuscript presents a fully guided reading of the youth book. We know the name of our guide because the elaborate preface, with many ruminations on the nature of friendship, is signed “Wang Jinwen of Beiping,” dated to the sixteenth day of the tenth month of 1815 at his studio in the capital, and stamped with his seals (fig. 1). In the preface Wang tells that, being fond of the minor genres of literature, he had “chanced to buy” a copy of the book; being deeply moved by the story, he decided to make an annotated version of it. In the ensuing pages, each of the five scenes of the story is followed by a commentary by Wang, whose notes also appear in smaller characters in the spacious top margins of pages. Given that the entire manuscript is written in the same hand, we have reason to believe that the text was personally copied by Wang, although we can’t be completely sure. What we can be sure of is that it was not a first draft; rather, the orderly appearance of the writing suggests a book intended for perusal.

Varying from philosophical contemplation to sympathizing with the fate of the story’s protagonists, to still more personal reflections, the notes and commentaries reveal Wang to be a learned and avid reader, versed in the Classics while being keenly interested in the vernacular genres of drama and fiction. An appendix entitled Shenjiao geyan (“Axioms on making friends”), comprised of quotes and passages gleaned from various classical texts, concludes the book respectably with wisdom from the world of Confucian learning.

The story from which the manuscript takes its title, Yu Boya smashes his zither to mourn a dear friend, centers on the friendship between Zhong Ziqi and Yu Boya, a legendary master of the qin (a zither-like instrument) from the Spring and Autumn period (770-476 BCE). The youth book appears to have taken its plot from a version of the well-known tale featured in the 17th century short story collection Jingshi tongyan (“Words to admonish the world”) edited by Feng Menglong (1574-1646). As told by the youth book, Boya was a minister and Ziqi a rustic woodcutter, who encountered each other one autumn night while Boya was traveling by boat through the countryside. To the minister’s astonishment, Ziqi was wonderfully versed in the art of the qin, and was able to read from Boya’s music what he had on his mind – first the towering mountains, then the flowing river. Barring worldly formalities, the two became the best of friends. While they made a vow to meet again at the same place a year later, Boya would return to find his friend no longer in the mortal world. In the final scene, a devastated Boya visits the grave of Ziqi, and, after playing his qin one last time, smashes it against the stone terrace – but for his friend, he would never play again.

The Chinese word for the best of friends, zhiyin (“one who understands the music”), comes from the tale of Boya and Ziqi; the prized, intuitive understanding of another’s mind has been extended to the experience of reading in Chinese literary criticism, where many a commentator has sought to authorize his own readings of a text with the claim of true understanding. Wang’s “edition” of the youth book thus appealed to a larger commentarial tradition whose influence was felt not only in the prestigious classical genres of poetry and prose but also in vernacular fiction and drama. In applying commentary to a youth book, Wang demonstrates his confidence in the minor genre of verse narrative as worthy of literary attention.

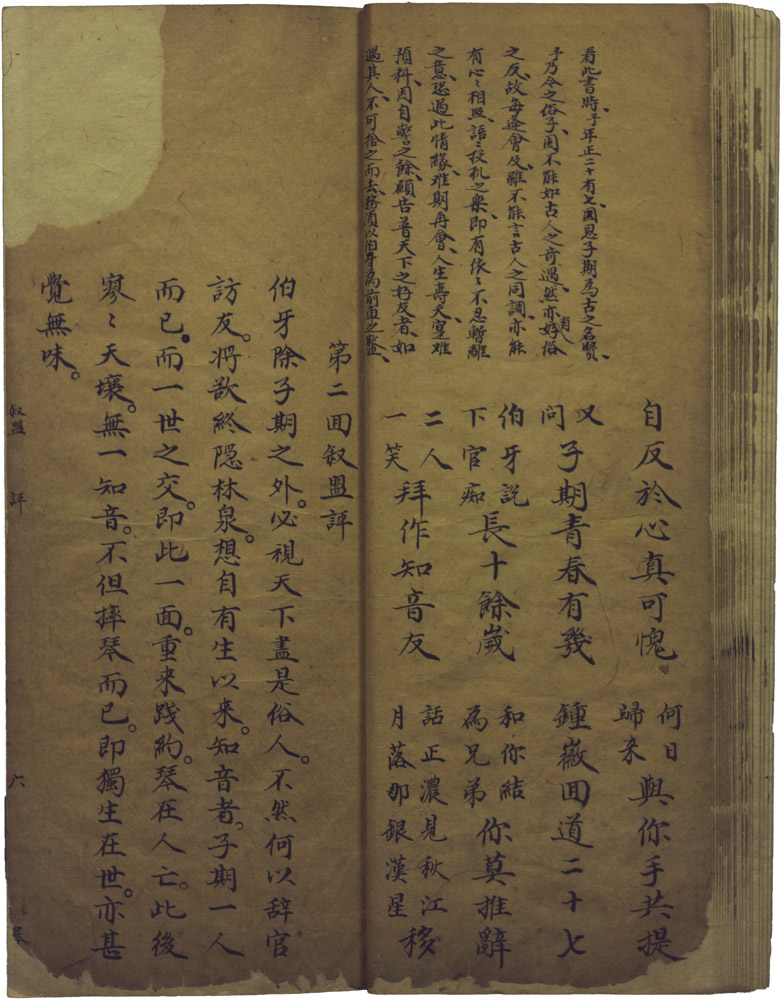

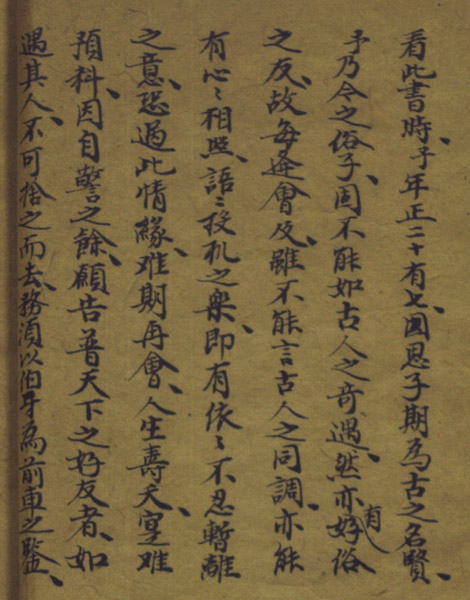

Wang’s commentaries are charmingly personal while attentive to potential readers. In the scene “The bond,” just before Boya and Ziqi seal their friendship, Boya asks Ziqi his age and Ziqi tells that he is twenty-seven. Wang divulges in his marginal commentary above the main text (fig. 2):

“Reading this book, I am just now age twenty-seven. I’ve been thinking, Ziqi was a man of virtue famed in antiquity, while I am merely a crude man of the present, so naturally I can’t have the marvelous encounters of the ancients. But I, too, have friends who are fond of my crudeness, so that every time we meet, though we can’t speak of having the same sentiments as the ancients, we can still share the joys of heartfelt understanding and the happy meeting of words. It follows that there arises the feeling of not bearing to part, for fear that when the present gathering is dispersed, it shall be hard to meet again. Life and death are truly hard to predict. And so, besides cautioning myself, here is to all who are fond of friends: if one encounters the person, do not leave him behind; one must take Boya’s case to be a lesson.”

In his preface, Wang divulges that he had dropped out of school early in his youth, and playfully professes in a couplet: “An outsider to the world of letters / I’m an insider of the markets.” One might ponder the deeper meaning of these lines. Given his apparent familiarity with commentarial conventions and his many allusions to his own “worldliness,” he may perhaps have been acquainted with the book trade. We have nevertheless no direct information on his livelihood, the book he had bought and copied from, or his exact intentions for the finely prepared manuscript. But surely was he aware of a community of readers who, like himself, enjoyed reading, writing, and pondering, who sought sympathetic company in reading as in life, and who were “fond of friends.”

References

- CHEN Jinzhao 陳錦釗 (1977): Zidishu zhi ticai laiyuan ji qi zonghe yanjiu 子弟書之題材来源及其綜合硏究. Unpublished PhD thesis. National Chengchi University, Taipei.

- CHIU, Elena (2018): Bannermen Tales (Zidishu): Manchu Storytelling and Cultural Hybridity in the Qing Dynasty. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center.

- CUI Yunhua 崔蕴华 (2005): Shuzhai yu shufang zhijian: Qing dai zidishu yanjiu 書斋与書坊之間: 清代子弟書研究. Beijing: Beijing daxue.

- ELLIOT, Mark C. (2001): “The ‘Eating Crabs’ Youth Book”. In: Susan Mann and Yu-yin Cheng (eds.): Under Confucian Eyes: Writings on Gender in Chinese History. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 262-81.

- FENG Menglong 馮夢龍 (1624): Jingshi tongyan 警世通言 [Words to admonish the world], juan 1. Collection of the Tōyō Bunka Kenkyūjo, call number 仁井田-集-N4038. http://shanben.ioc.u-tokyo.ac.jp/main_p.php?nu=D8621501&order=rn_no&no=04436 (accessed on 09/12/2018).

- GOLDMAN, Andrea (2001): “The Nun Who Wouldn’t Be: Representations of Female Desire in Two Performance Genres of ‘Si Fan’”. In: Late Imperial China, 22.1, 71-138.

- HUANG, Martin W. (1994): “Author(ity) and Reader in Traditional Xiaoshuo Commentary”. In: Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, and Reviews, 16, 41-67.

- WU Xiaoling (1982): “Suizhong Wu shi Shuanghun Shuwu suocang zidishu mulu” 綏中吳氏雙棔書屋所藏子弟書目錄 [Catalog of youthbooks collected by Mr. Wu of Suizhong in his Studio of the Two Silk Trees]. In: Wenxue yichan 文學遺產, 4, 150-56.

Description

Yu Boya shuaiqin xie zhiyin zidishu 俞伯牙摔琴謝知音子弟書

Depository: Capital Library of China

Shelfmark: yi (已) 401

Material: Paper, 43 folios, thread-bound (rebound)

Dimensions: 12.6 cm x 26.9 cm

Provenance: 1815, Beijing

Reference note

Zhenzhen Lu, “A Friend of a Lifetime: On Yu Boya smashes his zither to mourn a dear friend, a youth book”

In: Wiebke Beyer, Zhenzhen Lu (Eds.): Manuscript of the Month 2017.10, SFB 950: Hamburg,

http://www.csmc.uni-hamburg.de/publications/mom/70-en.html

Text by Zhenzhen Lu

© for all pictures: Capital Library of China