No 67

The Grave Side of Fengshui

Given the popularity of fengshui nowadays, it is easy for most of us to assume that its sole purpose is to help create a harmonious house, office or garden by bringing positive energy to a space. The term literally translates as ‘wind-and-water’ and has entered our common vocabulary to denote the general qualities of an environment. It was actually coined in the Song Dynasty (960 - 1279) to describe an important form of divination rooted in China’s long tradition of geomancy, which also dealt with the location of gravesites and the orientation of tombs. A manuscript in the British Library’s Stein Collection, produced during the late ninth and early tenth centuries, offers fascinating insights into the development of these practices.

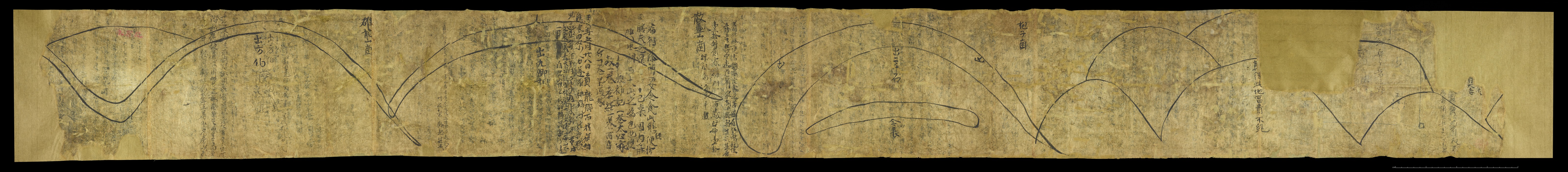

Manuscript Or.8210/S.3877 is a horizontal scroll made of eight sheets of very thin yellow paper (fig.1). Discovered in the so-called Library Cave (Cave 17) near Dunhuang, it was brought to England by the explorer Marc Aurel Stein following his second mission to Central Asia, from 1906 to 1908. Now at the British Library, the scroll was recently conserved so it could be digitised. To a certain extent, age explains why it is fragmented, but its vulnerable condition is also due to the fact it was extensively used before being placed in the cave. Judging by the quality of the paper, almost see-through, and the mediocre hands in which the texts were written, it most probably served a practical function. The manuscript was also ‘recycled’ several times during its lifetime.

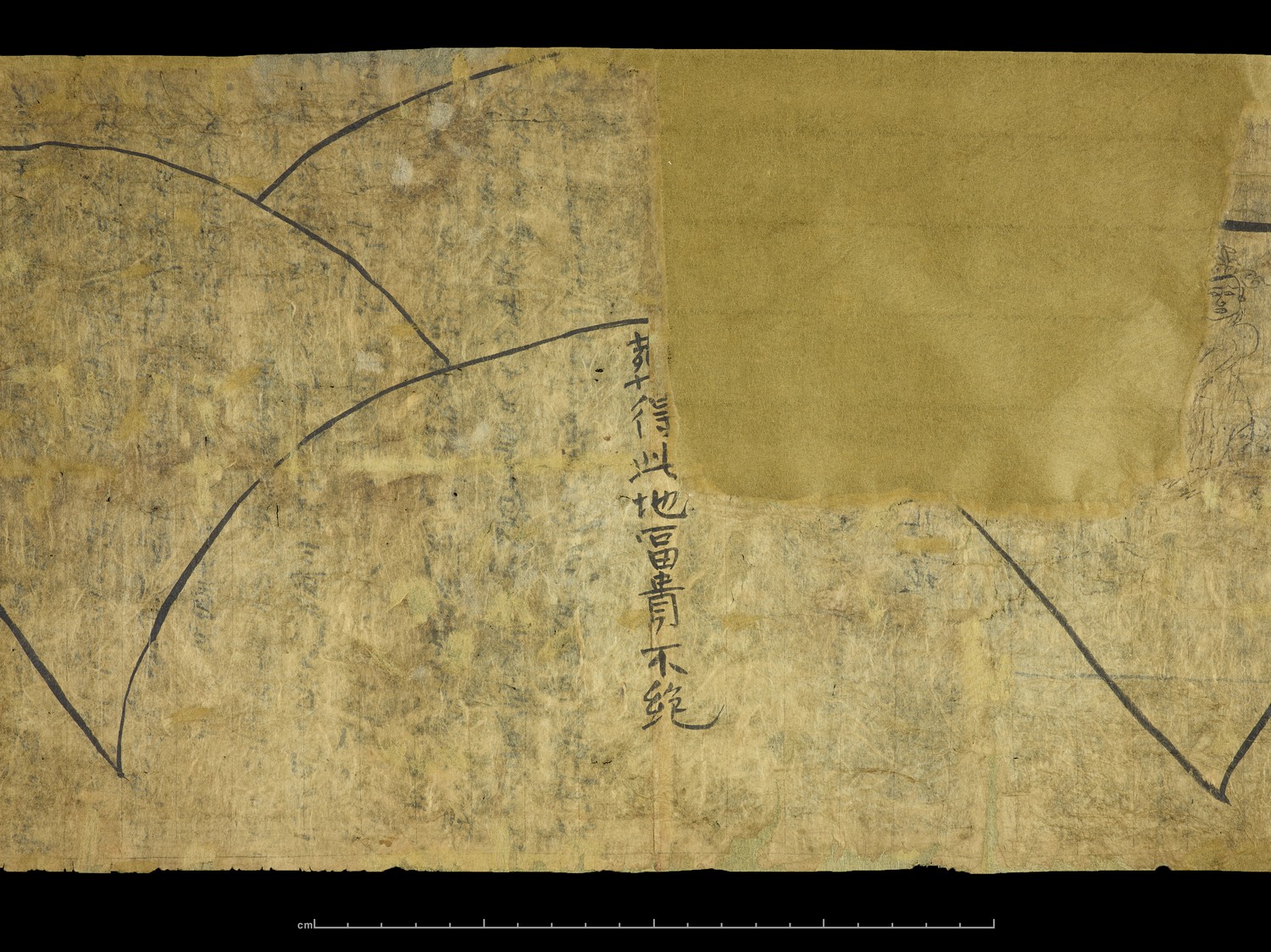

One side of Or.8210/S.3877 has an intriguing series of large drawings spanning its surface. Their even distribution across the two-meter long scroll suggests that they may have been the first elements to appear on it, although faintly visible guidelines and margins indicate that this side had originally been prepared for text. The drawings are related to geomancy, an ancient Chinese form of divination that led to practices better known now as fengshui. They offer guidance on where best to position a grave in relation to the surrounding landscape. Four different landforms are depicted, each accompanied by comments designating which locations to choose or to avoid for a family tomb. For instance, a caption in the middle of a mountainous landform indicates: ‘burying one’s parent here will bring unending riches and honour’ (zang de cidi fu gui bu jue) (fig. 2). Several other captions allude to the various official ranks that can be attained by descendants depending on the spot selected for their forebears. Likewise, bad sites, considered a potential source of misfortune, are singled out with the character xiong, meaning 'ominous' or 'inauspicious'.

At a time when paper was an expensive commodity (even the lower quality paper used for this scroll), the fact that the sketch spreads over the entire length of the manuscript also reflects the significance of such a document, designed to help local people wanting to bury their forebears. While the first topographical configuration is incomplete, the names of the following three landforms can be discerned in the manuscript’s extant sections: Baozi gang 抱子崗, Sangai shangang 散盖山崗, and Xionglong shangang 雄龍山崗. These could have corresponded to actual places from the Dunhuang region, but could equally refer to particular shapes of hills. If this were the case, the scroll would be something like a map of ideal types, displaying the range of land formations that one may encounter.

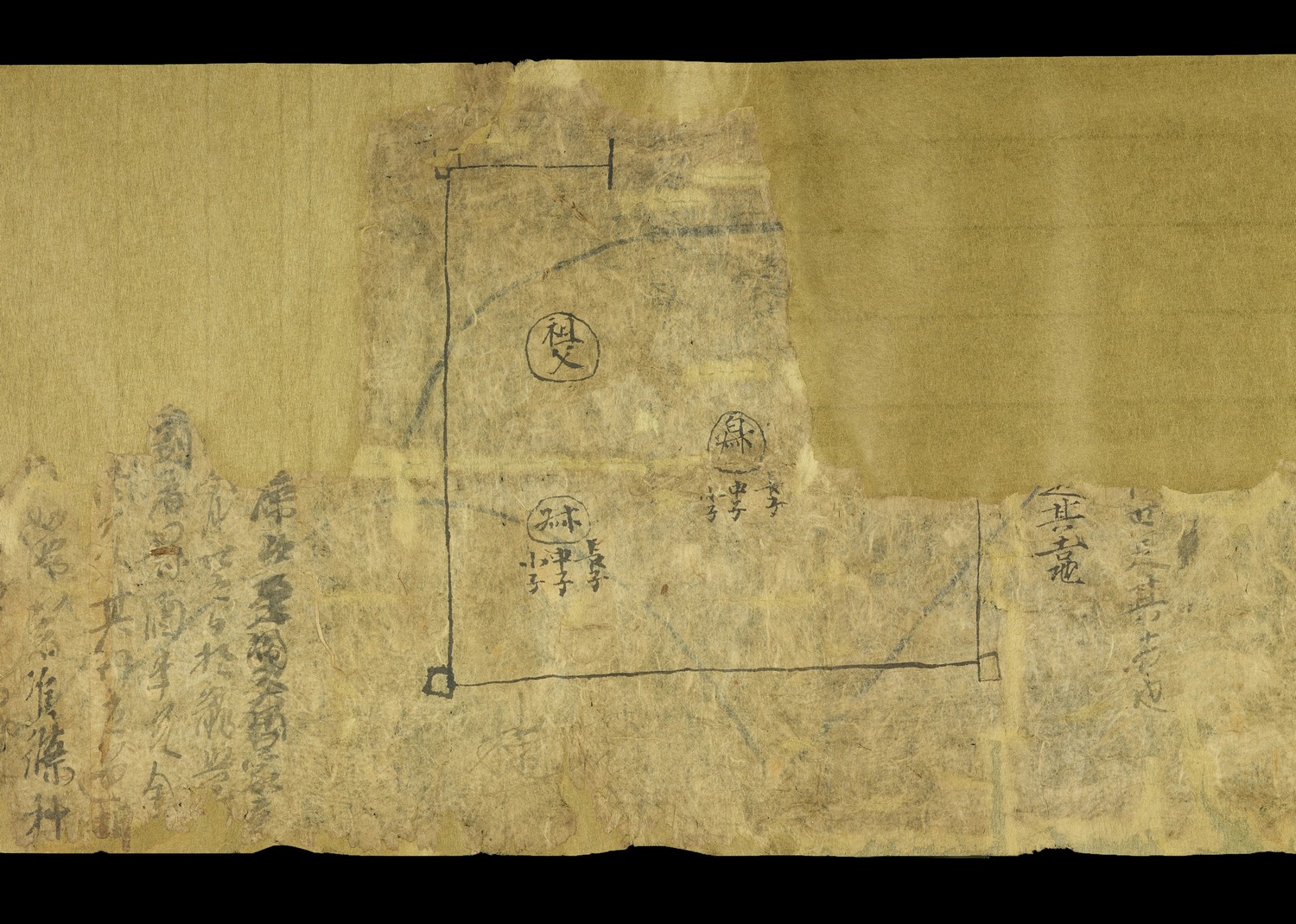

Probably at a later stage, a diagram of a similar nature was added to the verso of the scroll. Drawn by another hand, it shows how the tombs of three successive generations ought to be distributed and oriented within the same auspicious family burial site (fig. 3). With circles representing burial mounds, the diagram depicts the grave of a ‘grandfather’ (zufu) and those of two of his sons, placed diagonally across from him. The latter two are to be buried with their offspring, and are referred to as the father’s brothers.

A fourth grave, dedicated to the ‘father’ (fu), might have been drawn on the now missing upper right side of the diagram. This is quite possible considering that another scroll in the British Library's Stein Collection, Or.8210/S.2263, also bears a similar representation. The latter document is thought to have belonged to a teacher at the Prefectural School of Dunhuang by the name of Zhang Zhongxian張忠賢 because it contains a draft of his preface, dated 896, to a treatise on funerary geomancy entitled Zanglu (Records of burials). Zhang may not be the author of any of the sketches on our manuscript, but this information tells us that the local administration attached importance to divination and that geomancers themselves were active in official institutions. Individuals working in the same circles, whether students or experienced diviners, could have created the geomantic drawings on Or.8210/S.3877.

Our manuscript seems to have eventually fallen into disuse and came to be utilised as scrap paper, a phenomenon not so uncommon among manuscripts from Dunhuang. It could be that lay students, who were practising their literacy skills, gradually added various scribbled notes, characters and texts over the original drawings. One thus finds Chinese book titles, one lay society circular, two doodles and contracts on the recto of the scroll. Upside down on the verso, there is a poem as well as several contracts, dated to 897, 902 and 909, which imply that the scroll was reused for different purposes over the course of the 9th to 10th centuries.

To conclude, the scroll suggests that finding the right location for graves was an important concern in medieval China. Because where one was buried was seen to influence the fate of both the resident of a tomb and that of succeeding generations, we can see how geomancy came to be perceived as a way to influence the future by ensuring good fortune to one’s descendants. In addition, it appears that local people from the Dunhuang area resorted to the services of trained geomancers who were able to make siting recommendations. Yet, many questions remain unanswered. Who did the scroll originally belong to? Who was it for? How did the manuscript end up in the hands of lay students? And why was it eventually deposited inside the Library Cave alongside Buddhist texts and paintings?

References

- GALAMBOS, Imre (2016): “Scribbles on the verso of manuscripts Written by Lay Students in Dunhuang”. Tonkō shahon kenkyū nenpō 敦煌寫本研究年報, 10: 497-522.

- GILES, Lionel (ed.) (1957): Descriptive Catalogue of the Chinese Manuscripts from Tunhuang in the British Museum. London: British Museum.

- JIN Shenjia 金身佳 (2006): “Dunhuang xieben zangshu zhong de gudai Dunhuang sangzang minsu 敦煌寫本葬書中的古代敦煌喪葬民俗”. Journal of Hunan University of Science and Technology (Social Science edition) 湖南科技大學學報(社會科學版), 9, 96-100.

- KALINOWSKI, Marc (ed.) (2003): Divination et société dans la Chine médiévale. Étude des manuscrits de Dunhuang de la Bibliothèque nationale de France et de la British Library. Paris: Bibliothèque nationale de France.

- MAIR, Victor H. (1981): “Lay Students and the Making of Written Vernacular Narrative: an Inventory of Tun-huang Manuscripts”. Chinoperl Papers, 10, 5-96.

- WHITFIELD, Susan and SIMS-WILLIAMS, Ursula (eds.) (2004): The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War and Faith. London: The British Library.

Description

British Library, Stein Collection, London

Shelf-mark: Or.8210/S.3877

Material: ink on paper, 8 sheets

Size: 23.8 cm x 228.6 cm

Provenance: 9th-10th centuries, Dunhuang, Chinese Central Asia

Reference note

Mélodie Doumy, “The Grave Side of Fengshui”

In: Wiebke Beyer, Zhenzhen Lu (Eds.): Manuscript of the Month 2017.07, SFB 950: Hamburg,

http://www.csmc.uni-hamburg.de/publications/mom/67-en.html

Text by Mélodie Doumy

© for all pictures: British Library Board, London