No 63

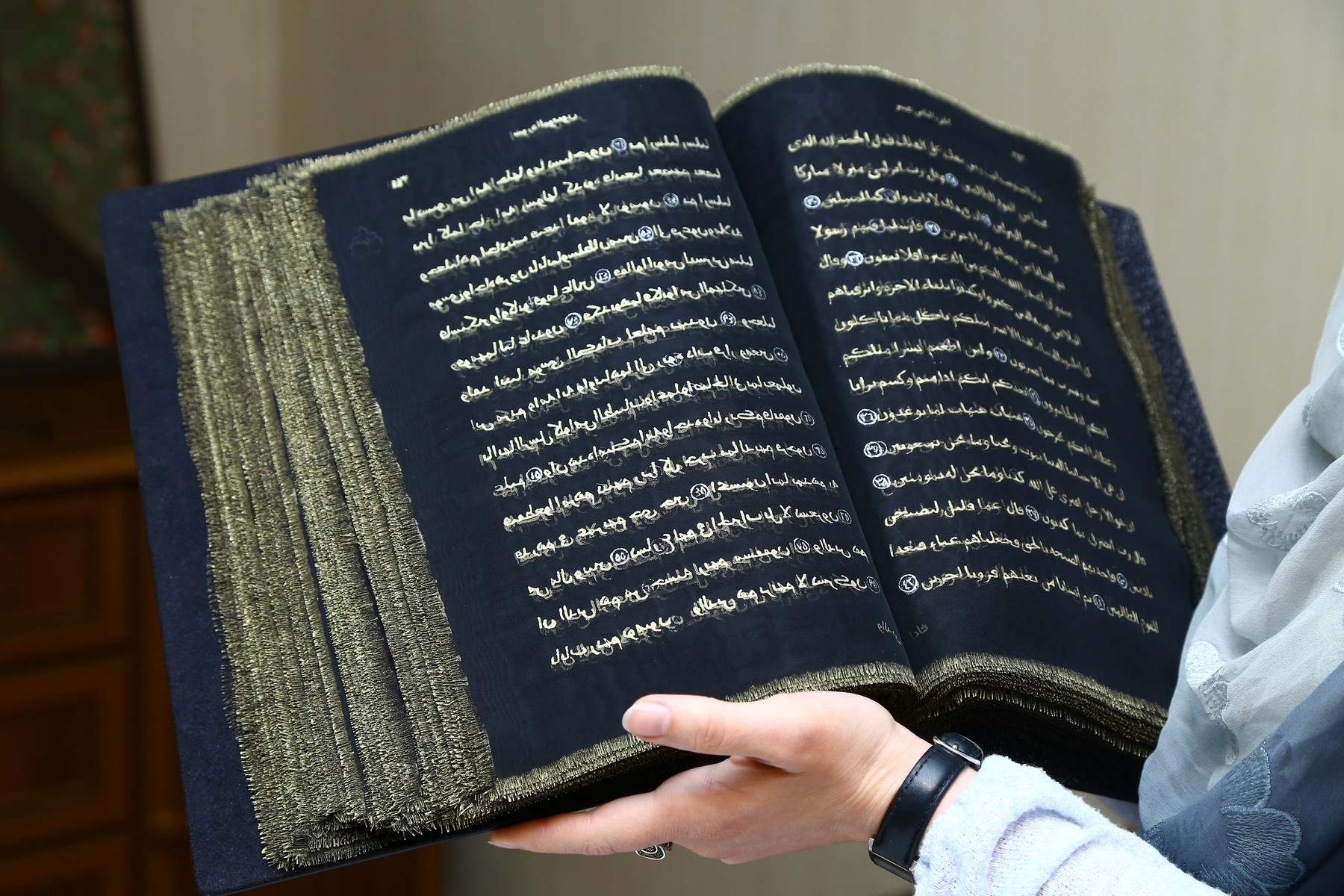

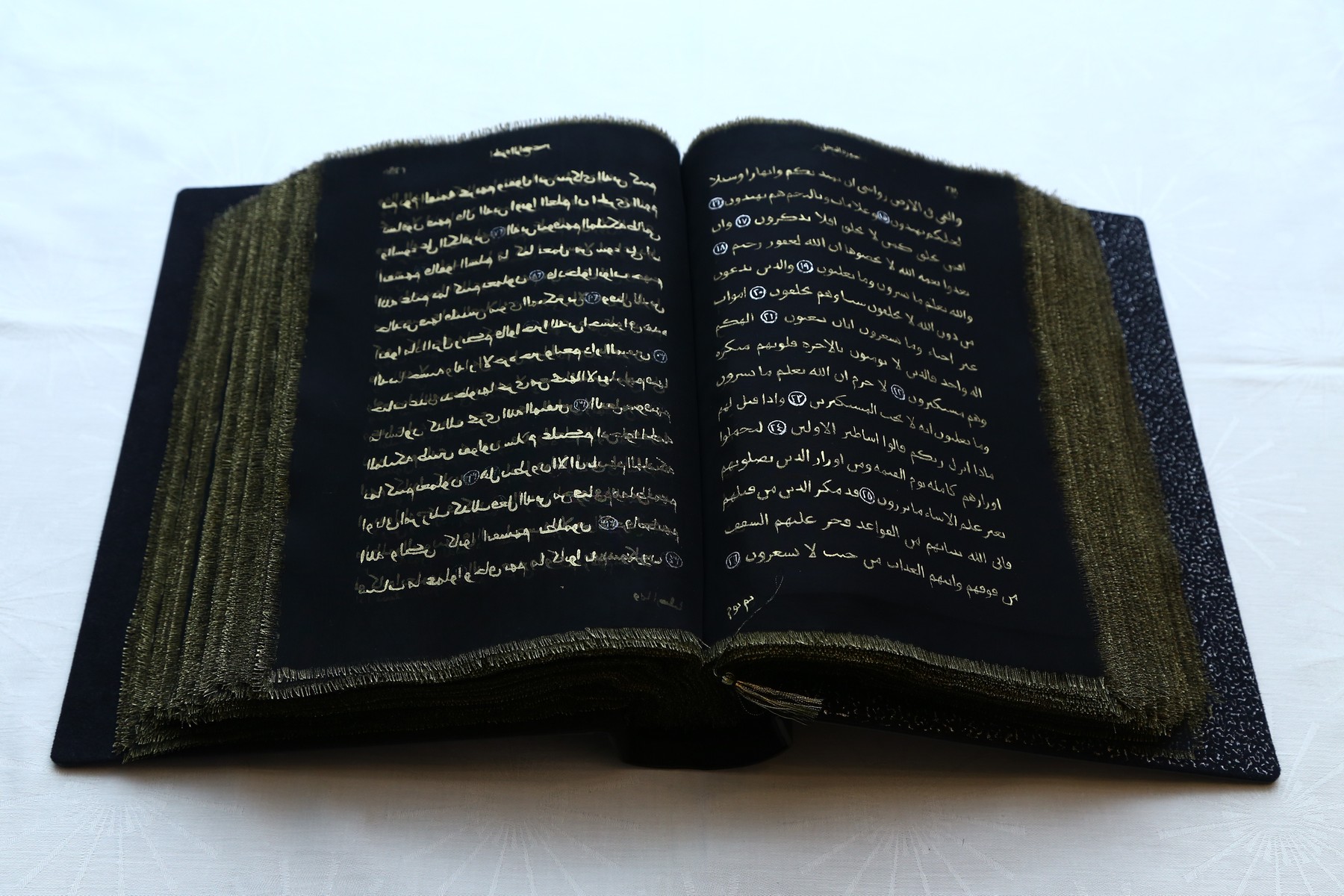

The Silk Qur’an

The word ‘manuscript’ usually makes people in Europe and the Middle East think of writing on parchment or paper. Writing texts on silk is rare here (or even unique). The Azerbaijani artist Tünzale Memmedzade did just that, however, and wrote the whole Qur’an – the holy scripture of Islam – on black silk. Two members of CSMC asked her a number of questions they had always wanted to ask a scribe of this kind. Here is their interview with the artist, Tünzale Memmedzade.

The artist

Tünzale Memmedzade studied Art History at Marmara University in Istanbul and is currently working on her PhD there. She has been painting for 20 years. Designing works of art on transparent silk was a decision she made at an early point in her career, she says:

‘While I was an undergraduate at university, we often worked on academic paintings. I found it a bit dull to use the same techniques that painters had already been employing for centuries, so I started painting on silk instead – I wanted to create a style that was new and my own. My work was well received, and since I enjoyed doing it, I just carried on.’

Since she wanted to produce a book made of silk one day, she decided to work on the Qur’an, which no-one had ever written on silk before. That was actually one of the main reasons she chose it:

‘I wouldn’t have wanted to do the same thing again if someone had already done it’.

It took her three whole years to produce a silk copy of the holy book by hand, as it wasn’t the only work she had to do at the time.

‘The Qur’an project was the most important thing for me at the time, but even so, I didn’t neglect my education, of course; I worked on architectural projects as well.’

The writing process and the work itself

Before the Qur’an can be copied, certain rules and rituals have to be respected.

‘If a woman wishes to make a copy of the Qur’an herself, then she usually has to cover her head first. I also covered mine this way as it’s customary here. Apart from that, you need to wash yourself in a specific religious ritual.’

The Qur’an is written in Arabic using Arabic script. The artist acquired both of these skills at school. Nowadays, she particularly uses the Arabic alphabet in her artwork.

‘I didn’t have to learn it again as I use it in my pictures. I can read Arabic, but I don’t understand what the words actually mean’.

Tünzale based her silk version of the holy book on a facsimile edition of the Qur’an, which was issued by Diyanet, the Turkish Directorate of Religious Affairs. She copied the text word for word and adopted the style of writing, page layout and design used in the original work.

She used around 50 metres of black, transparent silk for the manuscript and cut it to a size of 29 × 33 cm to make each sheet.

‘Obtaining all the material I needed turned out to be very costly, so I decided to make a smaller version of it instead.’

To write the actual text, she used a total of 1.5 litres of gold and silver ink.

‘When I started producing pictures on silk, I discovered that gold and silver look perfect on a black silk background. I wrote the text in golden letters and used silver to number the suras and draw the ornamental elements on each page. The colours I use are special ones designed especially for fabric. Since I’ve been using these paints in my pictures for a long time now, I know they won’t cause any problems or damage to the material.’

Since Tünzale has been working with silk for many years, she is very experienced in handling it.

‘The silk is stretched in a frame, and the lettering or pictures are then applied with brushes made of natural materials. Sometimes the text is sketched lightly on the silk first, but not always. To make the Qur’an, the pages were each cut to size by hand and then the edges of them were unravelled carefully, painted and ornamented. Once that was done, I wrote the suras on the silk sheets, but without stretching them in a frame this time.’

The writing on the sheets is smooth and regular and doesn’t contain any mistakes at all. That’s not to say copying the verses was all plain sailing, though...

‘I made mistakes on three pages, so I had to write those again. I didn’t have any other slip-ups apart from that, though. If you make a mistake as you write, you have to do the whole thing again on a new page because you can’t just wipe paint off silk. It’s the same with all my pictures on silk, too. Silk isn’t very forgiving when it comes to writing and drawing on it.’

Although the typeface and page layout Tünzale used were adopted from her template, you can see one or two small differences here and there. The vocalisation and recitation signs, which are usually included in the Qur’an nowadays, are missing, for example.

‘In Diyanet’s edition, all the marks are there, but I decided not to copy them because I wanted to rule out the possibility of getting the vowel characters mixed up in the very small handwriting. I didn’t think there was any issue there as the very first Qur’ans we know of didn’t use any marks or dots either.’

Parts of the text are also decorated in places.

‘I decorated the titles of the suras and the numbers of the ǧuzʾ, which are the thirty equally long sections into which the Qur’an is divided. I didn’t just copy all the decorative elements completely, but made some changes to some of them.’

Use and reception

‘[The silk Qur’an] can be read, of course, and it has actually been read a number of times already. After being read and approved by Diyanet in Azerbaijan, I was given official permission to show it to the general public. First of all, it was exhibited in Azerbaijan, which is my home country. But we also received requests to display the manuscript in other countries as well.’

The silk Qur’an – a real work of art – has largely been well received, but it has also been subject to a certain amount of criticism. Tünzale Memmedzade has not only been criticised personally, but the work itself has, too, one bone of contention being her choice of such an unusual writing material.

‘Of course I get criticised. You can’t please everyone, can you? It’s perfectly normal to be criticised. But silk is a material that’s actually mentioned in the Qur’an. Once I found that out, I didn’t have any reservations about doing the project.’

Description

Book in private collection

Material: Silk, 119 folios, gold and silver ink

Dimensions: 29 x 33 cm

Provenance: Turkey, 21th century

Reference note

Wiebke Beyer, Janina Karolewski and Tünzale Memmedzade, “The Silk Qur’an”

In: Wiebke Beyer, Zhenzhen Lu (Eds.): Manuscript of the Month 2017.03, SFB 950: Hamburg,

http://www.csmc.uni-hamburg.de/publications/mom/63-en.html

© for all pictures: Tünzale Memmedzade