No 60

The Light of the World in the Form of a Manuscript

In most people’s minds – in the European cultural sphere, at least – Christmas is associated with light and shimmering radiance. In the depths of the cold season, rays of light from burning candles and festive lights pierce the darkness. For Christians, this is the symbolic expression of their God made flesh in the person of Jesus Christ, whose birth is celebrated at Christmas time and who referred to Himself as ‘the light of the world’. This refulgence is made visible in the early-mediaeval Drogo Sacramentary.

In 823, Drogo, the twenty-two-year-old abbot of the Benedictine monastery at Luxeuil and illegitimate son of Charlemagne, became head of the bishopric of Metz. During his tenure, art production blossomed in this city in Lorraine, testified, above all, by the magnificent manuscripts that have survived. The Drogo Sacramentary, a work of this period dating from between 845 and 855, was produced for the Cathedral of Metz. In 1802 – during the French Revolution – it was relocated to the Bibliothèque nationale in Paris. The manuscript is structured in a remarkable manner and also exhibits unique pictorial invention.

Like all Gospel Books, the Drogo Sacramentary contains the four chronological accounts of the life of Jesus Christ. Such manuscripts, however, comprised far more than just a ‘fourfold biography’ of Jesus; from early Christianity onwards, they were used in religious services. Appropriate passages of text (‘pericopes’) were read aloud as part of the ritual surrounding the feasts of the liturgical calendar from the early mediaeval period (Christmas, Easter, saints’ days and so on). A list at the end of the codex enlists the respective festivals and the corresponding passages to be read aloud. A Gospel Book was considered to be the embodiment of Jesus Christ – after all, it contained the story of his life and also quoted the words that He had spoken, which were felt to be particularly holy. It was for these reasons that such manuscripts were venerated as if they were Christ Himself: during religious services, manuscripts were kissed, incensed, carried by covered hands only and ceremoniously enthroned. The high esteem in which manuscripts were held is reflected in the sumptuous cover of the Drogo Sacramentary. The surviving Carolingian front cover of the codex, which measures 32.5 × 24.5 cm, bears a central ivory plate with scenes from the Passion of Jesus Christ (figure 1). Encompassing the relief is an ornamented frame also in ivory, which, in turn, is surrounded by a wide decorative border comprising gold filigree rosettes set with gemstones. Mediaeval Gospel Books were frequently bound in such magnificent covers.

The Drogo Sacramentary actually contains much more than the texts of the four Gospels between its superb covers; it also features prologues to the history of the translation and to the canon formation, tabular overviews, lists of contents, and prefaces with information about the four Evangelists. When one leafs through the manuscript, one is particularly struck by the careful regularity of the lettering and the splendour expressed in its coloration and multitude of forms, not to mention the interspersed miniatures it contains.

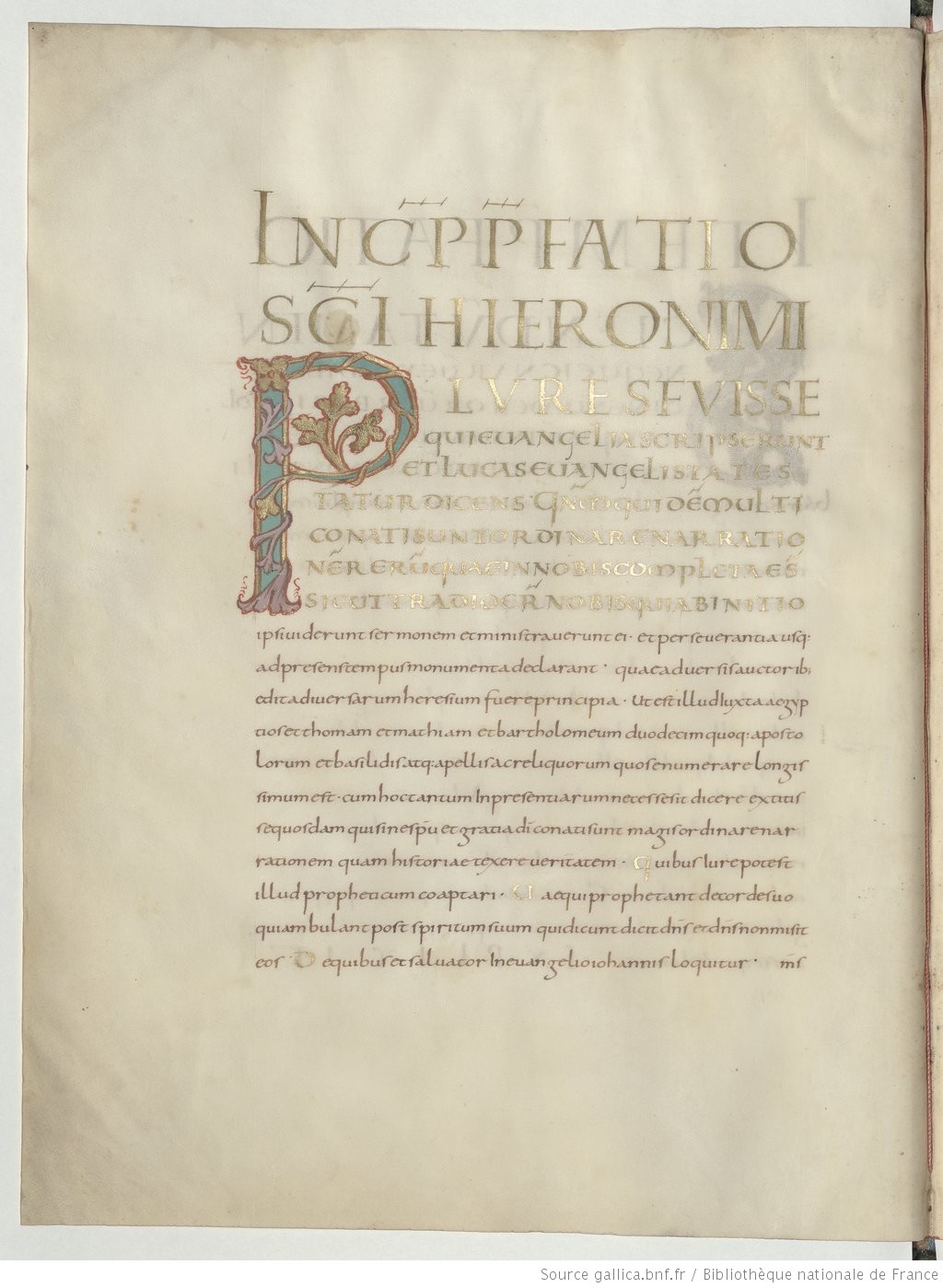

However, these varying decorative emphases are not merely employed to increase the value of the codex. Their primary purpose is to give expression to the visual hierarchies of the texts, the majority of which are written in dark-brown lettering known as Carolingian miniscule, a very simple, clear script. This uniform lettering is punctuated in a deliberate, regular manner, however. Varying types of lettering are used at the start of each respective text. The titles (incipit lines) are picked out in a very elegant gilt, reminiscent of the capital lettering seen on ancient inscriptions, known as capitalis. On the next level down in the textual composition, the initial letters of each sentence and section of text are also written in gold, albeit in a more rounded, simpler script. This highlighting of the script is accompanied by magnificent initials, which immediately draw the eye to the start of a new text or section of text (figure 2).

To arrive at the true start of the ‘Holy Scripture’, the respective gospels, the reader is required to leaf through quite a number of introductory pages first. Following on from the elaborate opening pages, or ‘incipit lines’, the beginning of each of the four gospels is laid out in a double-sided style; in each case, a large initial, representing the iconography of the Evangelist concerned and the first letter of the text, occupies a considerable proportion of the left-hand page. When one looks at the initial letters of St Luke’s Gospel (figure 3), for instance, one can see that the letter ‘Q’ is made up in part of the body of a winged bull, the symbol for St Luke. Its splayed hind hoof forms the downstroke of the letter. In the case of the other three Evangelists, the bodies of their respective symbolic beasts (in Matthew’s case an angel, in Mark’s a lion and in John’s an eagle) are artfully transformed into the shape of the initial letters. After this opening with its oscillation between script and image, the text continues over the entire double page in large, gilt capitalis letters, followed again by dark-brown miniscule once one turns the page.

Thanks to these decorative elements, the codex as a whole is composed in an entirely regular style. However, a further special means of accentuation is employed in a few places within the manuscript; sections of text are opened here with large initials entwined with tendrils, reaching down for several lines of text (figure 4). Within the interior space of some of the initials, small narrative scenes from the childhood of Jesus are depicted and relate to the following text. It is possible, for instance, to make out the Annunciation to the sleeping St Joseph, Jesus’s foster father; the birth of Jesus; and scenes from the life of St John the Baptist, who was considered to be the forerunner of Christ. The text following the initials also contrasts clearly with the more general script, since – unlike the rest of the text – it is not written uniformly in dark-brown miniscule, but in gleaming uncials. What, then, is the reason for emphasising these few sections of text?

It is helpful in this respect to cast a glance at the Capitulare evangeliorum, the list at the end of the Gospel, in which the pericopes to be read aloud during the various liturgical services are recorded in minute detail along with their opening and closing words. This list demonstrates that the highlighting of these few passages was not arbitrary, but was done with great precision. Nonetheless, one still needs to distinguish between the initials and the following sections of text in gilt uncial. On the one hand, there are passages in the manuscript that are opened with a purely ornamental initial (without any biblical scenes), and on the other, some pericopes start with what are known as ‘historiated’ initials, which depict images from the Gospels. The initials entwined with tendrils open the pericopes for the religious services for the feasts of St Stephen and the Apostles, Peter and Paul. These saints were of particular importance for the place where this manuscript was used: St Stephen was the patron saint of Bishop Drogo’s cathedral, and the church housed a very special relic – the staff of St Peter. Conversely, the ‘historiated’ initials, enclosing narrative biblical scenes, and the following passages of text, picked out in gilt, precisely mark the sections of text to be read aloud during particular festivities over the Christmas period. Thus, alongside readings for festivals of intimate importance to the Cathedral of Metz, textual passages relating to the Christmas liturgy are emphasised in the Drogo Sacramentary.

The particular emphasising of these sections of text allows one to conclude that the sumptuous Drogo Sacramentary was used for religious services on the days for which the corresponding pericopes were highlighted within it. Even today, one can imagine the overwhelming effect the gilt lettering must have had on the faithful. Once the gospel had been read aloud, the open codex would be lifted up and shown to the congregation in such a way as to ensure that the candlelight in the cathedral would bounce off the gilt lettering, thus making it appear to gleam. In St John’s Gospel, Jesus Christ described himself as ‘the light of the world’ (John 8:12). Therefore, it can be deduced that it was precisely at Christmas time, the festival of the incarnation of God becoming flesh in Jesus Christ, that this self-revelation would also be expressed in artistic form and the ‘divine’ light would be allowed to radiate out from the manuscript towards the faithful in the congregation.

References

- JAKOBI-MIRWALD, Christine (1998): Text – Buchstabe – Bild. Studien zur historisierten Initiale im 8. und 9. Jahrhundert. Berlin: Reimer, esp. pp. 53–58.

- LAFFITTE, Marie-Pierre / DENOËL, Charlotte (eds.) (2007): Trésors carolingiens. Livres manuscrits de Charlemagne à Charles le Chauve. Paris: Bibliothèque Nationale de France, esp. pp. 189–205.

- KOEHLER, Wilhelm (ed.) (1960): Die karolingischen Miniaturen, vol. 3, pt. 2: Metzer Handschriften, Berlin 1960, pp. 134–142.

- PALAZZO, Eric (1989): “L’enluminure à Metz au Haut Moyen Age (VIIIe–XIe siècles)“. In: François Avril et al.: Metz enluminée. Autour de la Bible de Charles le Chauve. Trésors Manuscrits des Églises Messines. Metz: Editions Serpenoise, pp. 23–43.

Description

Bibliothèque nationale de France

Shelf mark: Ms. lat. 9388

Material: vellum, 130 leaves

Dimensions: 265 x 210 mm

Date: Metz, AD 845–855

Content: the four Gospels and associated texts and indices.

Reference note

Jochen Hermann Vennebusch, “The Light of the World in the Form of a Manuscript”

In: Wiebke Beyer, Zhenzhen Lu (Eds.): Manuscript of the Month 2016.12, SFB 950: Hamburg,

http://www.csmc.uni-hamburg.de/publications/mom/60-en.html

Text by Jochen Hermann Vennebusch

© for all pictures: Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF)