No 59

A Gift from a Medicine Man

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the German missionary doctor Johannes Winkler (1874-1958) travelled to Sumatra to work on the western coast of Lake Toba. In two decades spent on the island, he contributed considerably to the establishment of the local healthcare system, while he also took great interest in the traditions of the indigenous Batak peoples. A local datu (medicine man), Ama Batuholing Lumbangaol, who had come to the missionary himself as a patient seeking treatment, became his friend. When Winkler left Sumatra for Hamburg, the datu equipped him generously with objects, masks, calendars, and two manuscripts on the subject of magic. One will be introduced below.

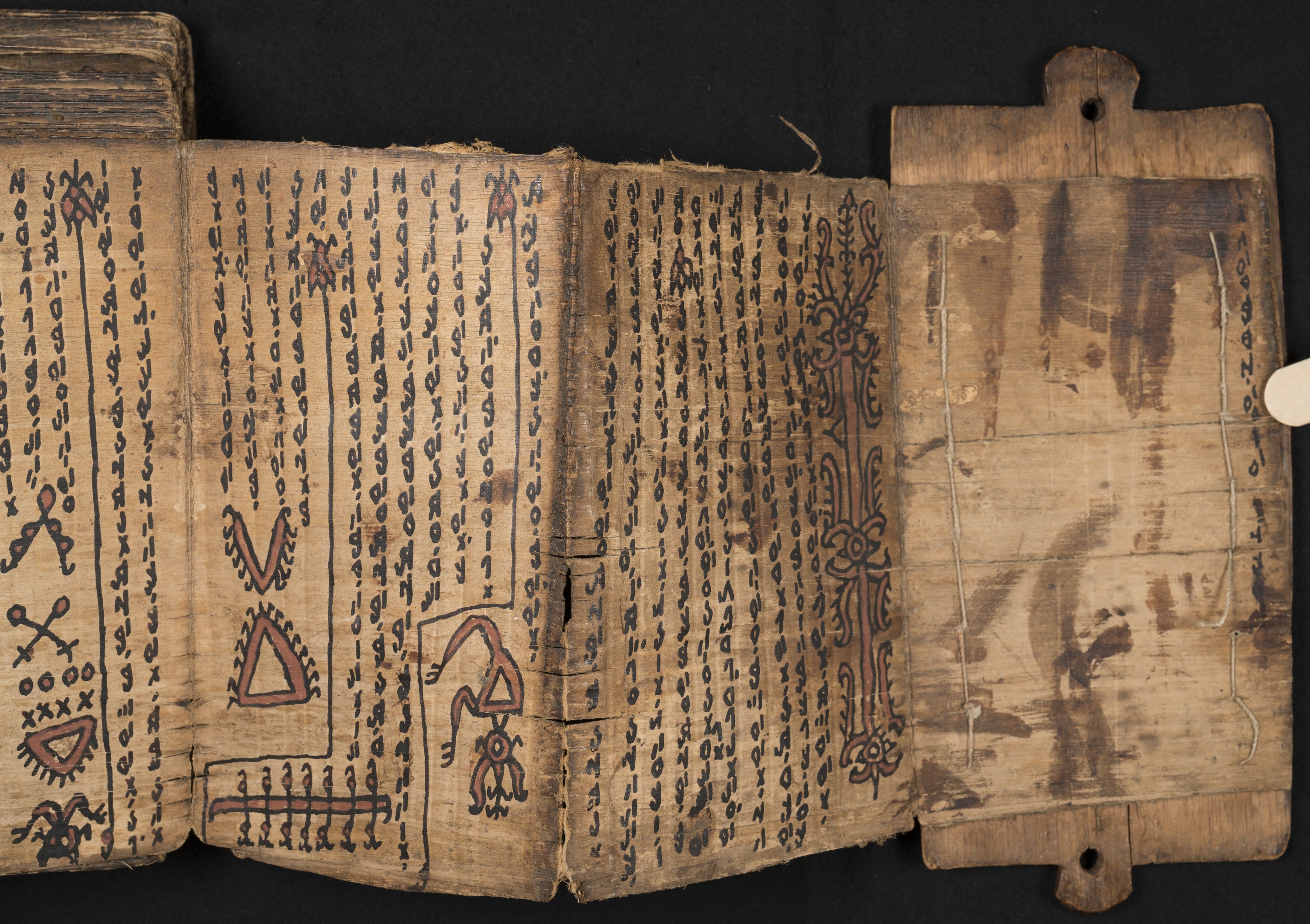

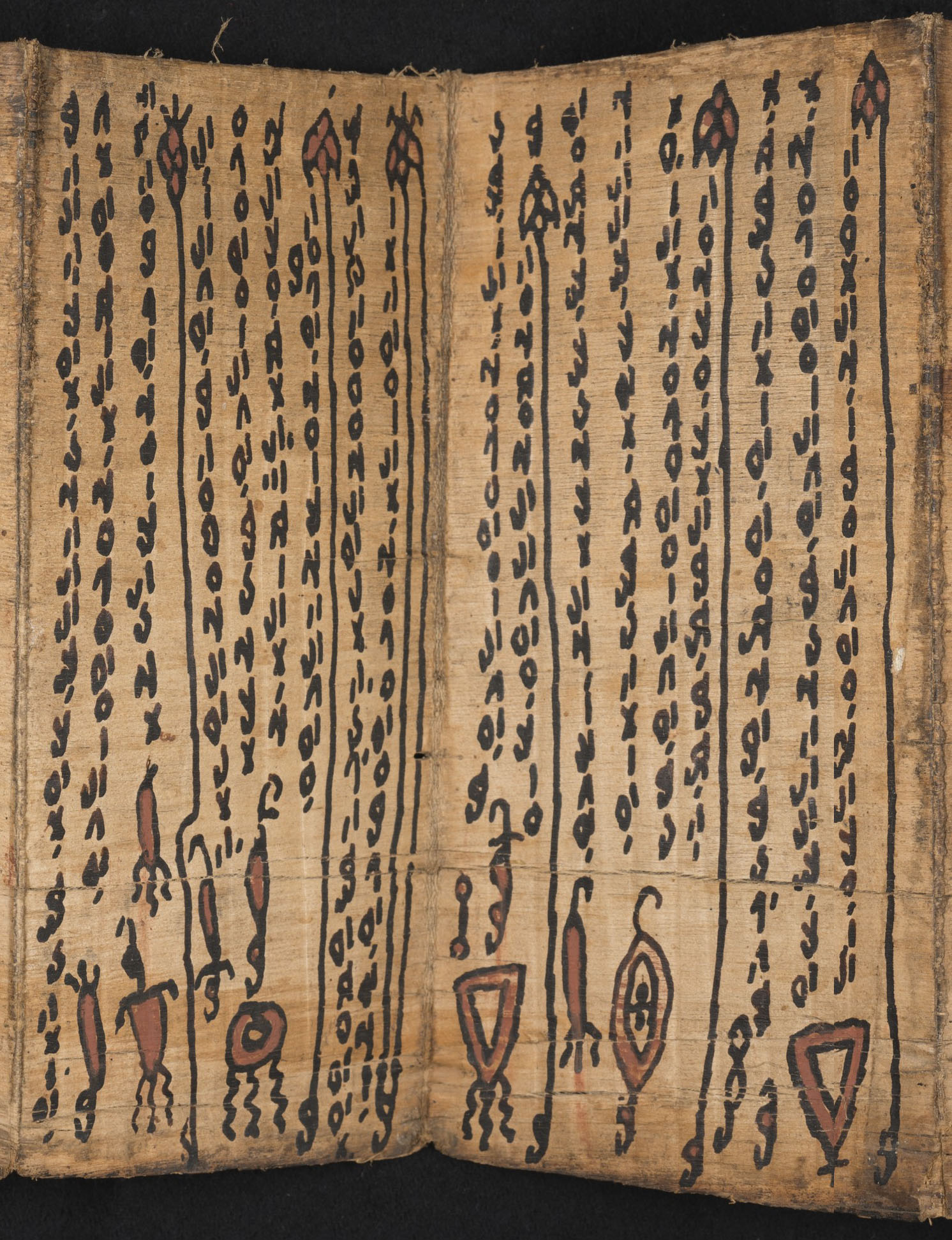

The manuscript is made from the bark of the indigenous agarwood tree (Aquilaria malaccensis), like other pustaha (derived from pustaka in Sanskrit, meaning ‘book’) of the medicine men and their pupils. Made from a long strip of flattened bark folded in concertina fashion, the manuscript consists of 48 folios, with two additional segments at each end fastened onto thick wooden covers. The folios measure between 17 and 19 cm in length and between 8 and 9.5 cm in width, and the covers are slightly larger. The front cover (fig. 1) is stitched onto the bark with thread; the back cover, which is glued on, bears traces of thread from earlier stitching. The front cover has ears on both sides, so that it can be fastened with straps, with which the book can be carried or hung. A plaited rattan band goes over the covers of the manuscript to hold the volume together. The manuscript is fully illustrated (see fig. 2), and deals with the various magical arts in the Batak tradition.

The folios are ruled to the folds and the text is written from left to right in black ink in Toba Batak, the language of the Batak people living around Lake Toba. The classical Batak script is called Surat Batak. This is a segmental writing system derived from the Brahmi family of scripts, in which consonant–vowel sequences are written as units, with each unit based on a consonant letter and an inherent vowel that can be changed using diacritical marks. Traditionally the knowledge of writing belonged to the datu, and the centuries-old writing system is uniquely associated with the literature of magic, medicine and divination. The pustaha, as notebooks which supplemented the oral transmission of knowledge from datu to pupil, often contained an assortment of information. These varied from remedies, amulets, and oracles to the darker art of preparing poisons and rites to destroy enemies.

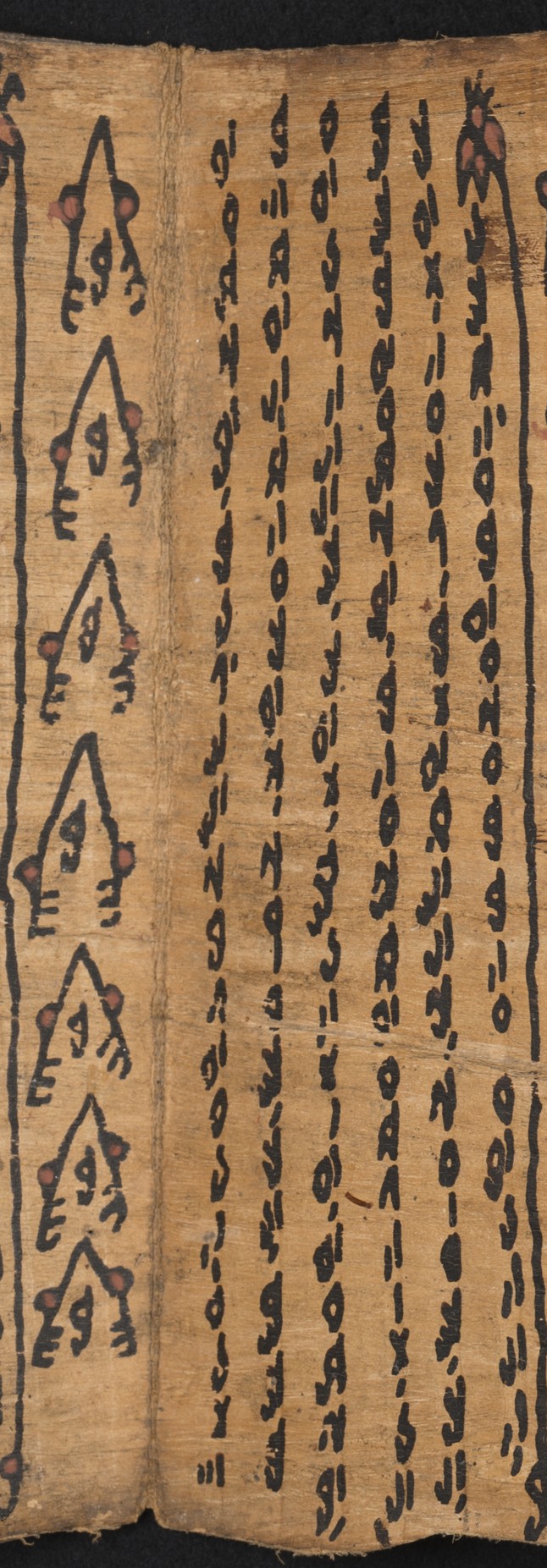

The manuscript given by the datu to Winkler provides a glimpse into the Batak magical tradition. For instance, it describes an agent of protection known as porsili (‘to replace’), which replaces warriors in battle and allows them to escape from danger. The text is accompanied by small drawings in red and black ink which seem to represent some kind of weapon or shield (fig. 3).

The manuscript also describes a black magic ritual, the pangulubalang (literally ‘chief of the army’), a powerful occult weapon in war. The text describes how to summon the pangulubalang, a terrifying spirit, from a dead enemy’s body. Furthermore it explains the gruesome process of how to extract the magical substance pupuk from the dead enemy. This substance can be applied to human or animal effigies to animate them against both human and demonic enemies. To activate its full effect, special images must be drawn onto the surface of everyday objects using the substance.

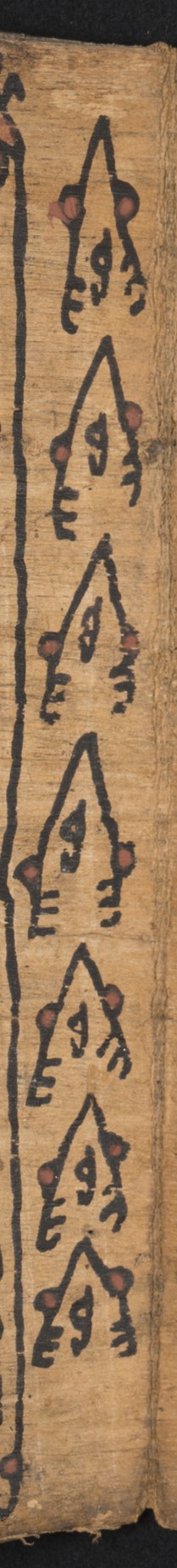

Towards the end of the manuscript, the text provides instruction on pagar surat na sappulu sia, a form of protective magic using the nineteen letters of the Batak script. In this section, each paragraph of the text contains a drawing in red and black which represents a deity, whose name comes from a Batak letter. To give an example:

Ahu ma debata ni si Tata di Banua darajahon di halto na marurus,

Si pabungkar tu huta ni musunta

I am the deity Tata di Banua, drawn on a ripe fruit of the sugar palm, [will become] the destroyer of the enemy’s village (see fig. 4).

The personal pronoun ‘I’ is followed by the word for ‘deity’, then the deity’s name (in this sentence, ‘Tata’ is made up of a repetition of the Batak letter ta), and then ‘to be drawn’ and where. Following the text, the letter ta is drawn seven times in repetition (see fig. 5). Likewise, other sentences also start with ‘I am the deity’ in this fashion, followed by the name of the deity made up of the repetition of a different Batak letter, who will destroy the enemy or protect a village.

While in northern Sumatra pustaha still exist to the present day amongst the Batak, it is particularly difficult to obtain information about the magical traditions associated with them. Clearly, with the penetration of the Protestant religion into the most internal territories of the island, people have forgotten or wanted to forget about this past associated with black magic. At the same time, people still believe the manuscripts to be a vehicle of magical knowledge, and attribute the loss of magical power in their territory to the absence of these potent objects.

The exact circumstances under which this manuscript was prepared is unknown. For certain it preceded Winkler’s collecting interests. Possibly it was a textbook which the datu had written for his own students to learn the magical arts. Or perhaps it was commissioned by earlier missionaries interested in the local traditions. In any case, Johannes Winkler, the German missionary received it as a gift from the Batak medicine man Ama Batuholing Lumbangaol, who considered him equal in mind.

References

- CASPARIS, J. G. de (1975): Indonesian Paleography: A History of Writing in Indonesia from the Beginnings to A.D. 1500. Leiden: Brill.

- KOZOK, Uli (2009): Surat Batak: Sejarah Perkembangan Tulisan Batak. Jakarta: Ècole française d’Extrême Orient and Keperpustakaan Populer Gramedia.

- MONACO, Giuseppina. Lo studio dei manoscritti Batak, magia offensiva e difensiva. Unpublished MA thesis. University L’Orientale of Naples.

- PETERSEN, Helga / KRIKELLIS, Alexander (eds.) (2006): Religion und Heilkunst der Toba-Batak auf Sumatra – Überliefert von Johannes Winkler (1874-1958). Köln: Rüdiger Köppe.

- RICKLEFS, M.C., VOORHOEVE, P., and TEH GALLOP, Annabel (2014): Indonesian Manuscripts in Great Britain: A Catalogue of Manuscripts in Indonesian Languages in British Public Collections. New Edition with Addenda et Corrigenda. Jakarta: Ècole française d’Extrême Orient, Perpustakaan Nasional Republik Indonesia, Yayasan Pustaka Obor Indonesia.

- TUUK, H. Neubronner van der (1861): Bataksch-Nederduitsch Woordenboek. Amsterdam: F. Muller.

- TUUK, H. Neubronner van der (1971): A Grammar of Toba-Batak. Translated by Jeune Scott-Kemball. The Hague: Nijhoff.

- VOORHOEVE, Petrus (1961): A Catalogue of the Batak Manuscripts in the Chester Beatty Library. Dublin: Hodges Figgis & Co. Ltd.

- WARNECK, J. (1906): Tobabataksch-Deutsches Wörtebuch. Batavia: Landsrukkrij.

Description

Manuscript in private collection

Material: Wood (covers); bark (folios)

Dimensions: 17-19 cm × 8-9.5 cm (folios), covers slightly larger

Language: Toba Batak

Place of origin: North Sumatra, Indonesia

Date: Late 19th to early 20th century

Reference note

Giuseppina Monaco, A Gift from a Medicine man

In: Wiebke Beyer, Zhenzhen Lu (Eds.): Manuscript of the Month 2016.11, SFB 950: Hamburg,

http://www.csmc.uni-hamburg.de/publications/mom/59-en.html

Text by Giuseppina Monaco

© for all pictures: Helga Petersen. Photographs by CSMC