No 58

‘The excellence of such a noble and wise …’

– a praise from the 16th century

Scholars are obviously pleased whenever they gain important new insights in the course of their work, but if a trail of information happens to lead them off into a completely different field of investigation, that can be thrilling as well, as the example of a Qur’an manuscript with the shelf mark ‘Thurston 36’ shows. While examining this very small Qur’an manuscript kept by one of the Bodleian Libraries in Oxford, two scientists from the Centre for the Study of Manuscript Cultures in Hamburg (CSMC) noticed three pages full of symbols arranged in neat lines – obviously a script of some kind. They realised upon making this discovery that they simply had to work out the secret behind the mysterious writing. What they weren’t aware of at the time was where this would eventually lead them...

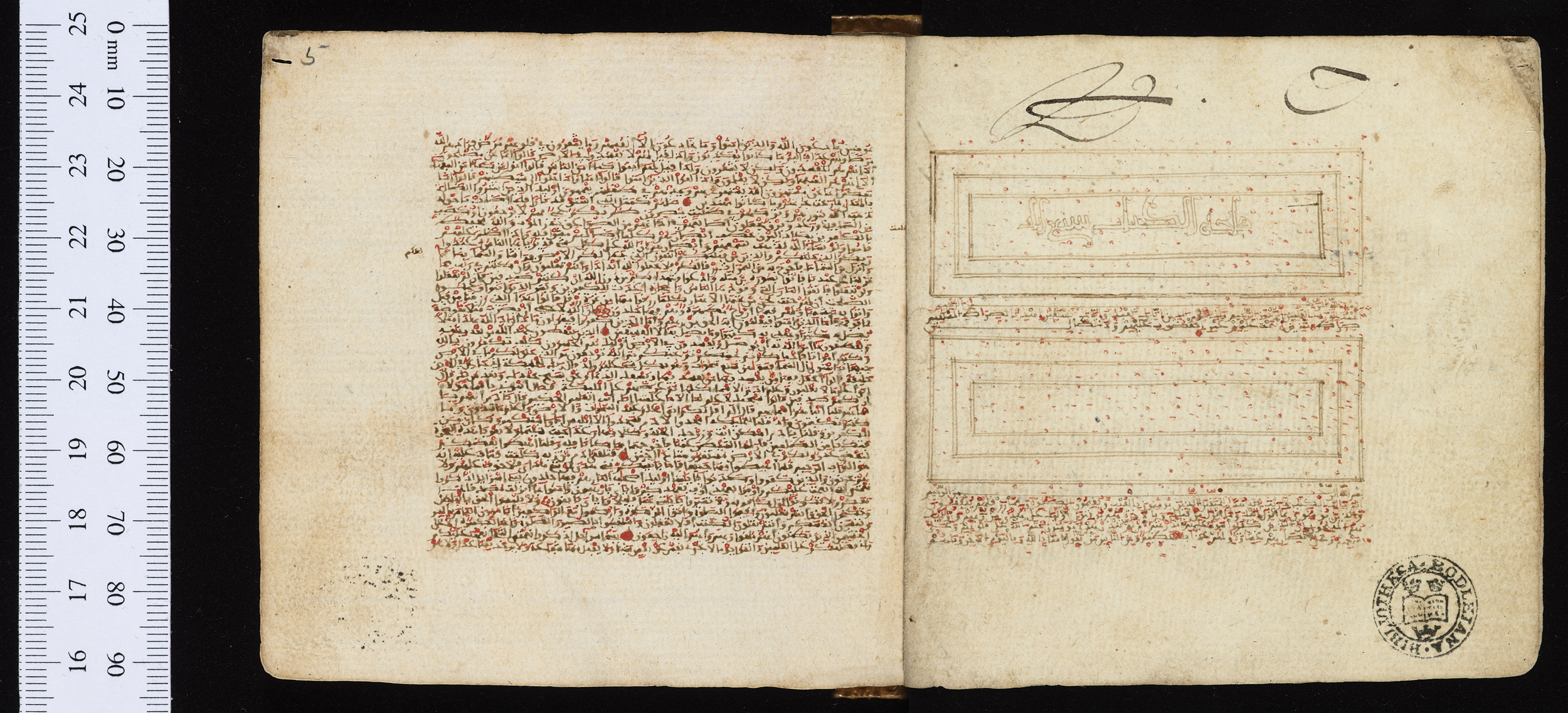

Thurston 36 is a small Qur’an manuscript written in Arabic and is approx. 9×10 cm in size. It is kept at Weston Library in Oxford, which is one of the Bodleian Libraries. The space between the lines of tiny handwriting is roughly 1.5 mm (see Fig. 1), which is why the entire Qur’an spans just 73 pages. Other miniature Qur’ans that reports say used to be worn on the body like amulets are often much smaller, being as tiny as 3.5 cm from edge to edge, but they are rarely able to match the size of the lettering and spacing between the lines of this meticulously written work. The style of handwriting it employs belongs to the family of Maghribi scripts, which are typical for the west of the Islamicate world. It is difficult to pinpoint it any more accurately than this, but the rather angular letters of the Oxford Qur’an indicate it may originally have come from Andalusia, where numerous dynasties of Muslim rulers held power until 1492.

Another clue is provided by the red and green vowel symbols typical of this region, which make it easier for the reader to recognise the words written largely in black consonants. The manuscript gives the impression of being incomplete, as a number of titles of surahs have been outlined in preparation, but not coloured in or gilded (Fig. 1). The Qur’an was written on European paper, which only replaced parchment in Spain and North Africa in the 15th century (parchment was used as a writing base for high-quality manuscripts such as Qur’ans up till then). In view of this, the manuscript is hardly likely to be any older. Not unusual for Oriental manuscripts stored in European libraries, the manuscript is enclosed in a plain leather binding of a European type, which presumably replaced the original cover after it got damaged or became too shabby to use any more.

This would normally be all that would interest a scholar in such a miniature Qur’an, but in this case, three astonishing pages precede the work that are full of mysterious letters that differ from the writing in the rest of the manuscript (Fig. 2). Most of these symbols are circles with up to three dots or strokes around them. The way in which these symbols are grouped together in units makes them look like words – are they a secret message, perhaps? Admittedly, ciphers are rare in Arabic manuscripts, but they are not completely unknown: texts concerned with alchemy or magic sometimes contain recipes that were encoded to stop readers unfamiliar with them from discovering their secrets, and a number of religious minorities hid some of their religious ideas by using cryptograms.

Yaʽqūb b. Isḥāq al-Kindī, a 9th-century Arab scholar, reported about various methods used to encrypt texts in Arabic. The simplest one was to replace each letter in the normal text with a different character – a symbol, a number or a different letter, for instance. The texts encoded this way can be decoded by determining how frequently the coded letters occur and then comparing this to the frequency with which letters normally occur in the language in which the text is thought to have been written. According to Al-Kindī, the letters that were used most often in the variety of Arabic spoken in his era were alif, lām, mīm, hāʾ, wāw and yāʾ (the most popular coming first). The first two occurred almost equally often and were (and still are) used to write ‘al-’, the definite article. One can therefore expect to see the symbols that correspond to alif and lām together in encrypted texts and at the beginning of a word. Taking a careful look at the frequency of the symbols used in this particular encrypted text reveals something different, however: the most frequent symbol – a circle with two dots above it, like an ö in German – occurs more than twice as often as the second most frequent symbol. What’s more, neither of them occur together very often. Ergo the text cannot be written in Arabic.

Since the manuscript eventually ended up at Oxford, it seemed plausible that the secret text might originally have been written in English. The most frequently used letter in this language is E, followed by T and A. Once the symbol that was most often used in the secret text had been replaced by E, it became apparent that the same combination of symbols – a three-letter word ending in E – occurred numerous times. This was probably the definite article, ‘the’, which is the word most frequently used in English. So two more letters had been identified now. A word containing the letters ‘TH_T’ presumably stood for ‘that’, an idea that provided the meaning of another symbol.

The two codicologists gradually worked their way through the mysterious piece of writing until they eventually made a great discovery: the text that was revealed behind all the symbols turned out to be a speech in praise of a number of outstanding figures in early modern England. First of all, Thomas More is mentioned, a scholar described as ‘noble’, ‘wise’ and ‘verteus’ (virtuous). The text goes on to say that More was Lord Chancellor in the twenty-second year of King Henry VIII’s reign. His daughters Margaret, Bes and Cecile, who all possessed an excellent command of Latin, Greek and Hebrew, were the object of praise as well. Margaret, in particular (who had already adopted her husband’s surname, Roper, by that time), is said to be the star among them: the noblest person ever to have lived in this world, both in terms of her beauty and her education. At the end of the laudatory text, the anonymous author refers to himself as her humble servant before finalising it with the year of its writing, 1531 – which does, indeed, correspond to the twenty-second year of Henry’s reign.

Most of the information contained in this secret text tallies with what we know about the people mentioned in it. Thomas More (1478–1535) was a respected humanist and personal advisor to the king for many years – until he dared to openly oppose Henry’s plans to marry Anne Boleyn and trigger a major dispute with the Pope. More subsequently stepped down from his role as Lord Chancellor in 1532, but since he continued to oppose the marriage, he was eventually imprisoned in 1534 and then beheaded a year later. Four weeks after his death, his eldest daughter, Margaret, who had also been the child closest to his heart, managed to bribe a guard and get hold of his severed head, which Henry had had impaled on a spike on London Bridge for everyone to see. The excellent education that Thomas More’s children and wards received, which is touched on by the secret message and confirmed by other sources, was unusual for that period of England’s history. Margaret Roper, who wrote a number of books herself as well as having translated several others, is now regarded as one of the best educated women of her time.

Since Thomas More was still in the king’s favour in 1531, it is unlikely that the text was encrypted for political reasons at that time. It may have been done because it was illegal – or at least disreputable – to own a copy of the Qur’an. What is most likely, though, is that the encrypted message was simply a playful pastime. In early modern England, cryptography was not only popular among politicians, spies and religious minorities, but it was a pastime that children and, indeed, whole families enjoyed. Thomas More even went as far as to create a language and script of his own for his philosophical novel Utopia. Unfortunately, we are unable to say exactly who it was who actually wrote the encoded lines in the manuscript, although it is likely it was someone who knew Thomas More and Margaret Roper personally. The first verified information we have on this manuscript is from a partly handwritten catalogue of books from 1605 kept by the newly-founded library of Thomas Bodley in Oxford. A year earlier, Sir Henry Wotton, whose family included a long line of diplomats, had bequeathed the manuscript to the library. It is certainly conceivable that one of his ancestors possibly had something to do with the Mores, either directly or indirectly, and consequently came to possess the manuscript himself, but we are quite unable to say how it had previously come to England from the western part of the Islamicate world.

The miniature Qur’an and the three pages of praise written in secret code have all the ingredients of a good mystery: although we have now been able to solve the first puzzle, which was the easiest one (cracking the code used to hide the secret message), doing so has triggered further questions that can’t be answered at present. Only time will tell.

References

- BERTHOLD, Cornelius; COLINI, Claudia: ‘The most noble of any that ever lived in this world’: An encrypted text praising Thomas More’s daughter Margaret contained in a miniature Quran from the Bodleian Library (in preparation).

- DAYBELL, James (2012): The Material Letter in Early Modern England. Manuscript Letters and the Culture and Practices of Letter-Writing, 1512–1635. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- McCUTCHEON, Elizabeth (2015): The education of Thomas More’s daughters. Concepts and praxis. In: Moreana, Liber Amicorum – Special Elizabeth McCutcheon, 52, nos. 201–202, 249–268.

- MRAYATI, Mohammed et al. (eds.) (2002): al-Kindi’s Treatise on Cryptanalysis (The Arabic Origins of Cryptology, vol. 1), translated into English by Said M. al-Asaad, Damascus: King Faisal Center for Research and Islamic Studies & King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology (originally Damascus 1987).

- REYNOLDS, E. E. (1960): Margaret Roper. Eldest Daughter of St. Thomas More, New York: P. J. Kenedy & Sons.

- WAKEFIELD, Colin (1994): “Arabic Manuscripts in the Bodleian Library. The Seventeenth-Century Collections.” In: Russel, G. A. (ed.): The ‘Arabick’ Interest of the Natural Philosophers in Seventeenth-Century England. Brill’s Studies in Intellectual History, 47, Leiden/New York/Cologne: E. J. Brill, 128–146.

Description

Oxford, Bodleian Libraries

Shelf mark: Thurston 36

Material: European paper, European leather binding

Size: 9×10 cm

Provenance: North Africa or southern Spain; England since 1531 (at the very latest)

Reference note

Cornelius Berthold and Claudia Colini, The excellence of such a noble and wise …

In: Wiebke Beyer, Zhenzhen Lu (Eds.): Manuscript of the Month 2016.10, SFB 950: Hamburg,

http://www.csmc.uni-hamburg.de/publications/mom/58-en.html

Text by Cornelius Berthold and Claudia Colini

© for all pictures, except the code transcription: Bodleian Libraries