No 57

‘Consider it worth a thousand cash’

One popular genre in China’s long history of written culture is the vocabulary list (zazi, literally ‘miscellaneous characters’). Developed centuries ago as a convenient way for students to learn how to read and write, they are texts containing words grouped into rhyming lines or phrases, designed to aid in memorisation. Both chanted aloud and written down, this humble literature once had a great role to play in the elementary education of ordinary people.

One example of a vocabulary list in my collection is introduced here. In January 2015, in the Panjiayuan antique market in Beijing, I purchased a manuscript entitled ‘Vocabulary list in six-syllable lines’ (Liuyan zazi) on its cover (see Fig. 1). It measures 19.68 cm (l) x12.06 cm (w) and consists of twelve folios, with writing on both sides except for the last folio, whose verso is blank. It is written on bamboo paper and bound in string with evenly-spaced four-hole sewing. The cover is signed ‘diligently recited by Wang Juhe’, which suggests that it was once owned by a student; we do not know if he was also the scribe. In several places in the manuscript, seals with the name ‘Xue Long’ indicate that this was the name of it previous collector.

Determining the date and provenance of the manuscript is difficult. It could date as late as the Republican era (1912-1949), as vocabulary lists were in use in many areas of China well into the 20th century. In older times there were both woodblock and lithographic printed texts (the latter were reproduced in great numbers from the late 19th century onwards), while there also existed a vibrant culture of hand-copying materials for one’s own use or for one’s students. Like other hand-copied vocabulary lists, this manuscript contains a number of non-standard characters (suzi). For me, this meant that while their meaning may be clear in context, finding them in a dictionary was not always easy.

Many questions exist as to just how vocabulary lists were used. A teacher may read them aloud with his students; the rhymes made them easy to memorise, and once students could recite the lines, they could also review the characters on their own. While elementary, vocabulary lists were almost never simply random compilations of words, but imparted important information and ideas. Sometimes the vocabulary was purely practical, such as the items sold in a general store or the tools used by labourers. Equally often, the texts taught ethics, historical concepts, and the organisation of society and government.

Our text begins by giving an overview of the formation of the world, from the separation of the earth and the heavens by the mythological figure Pangu to the creation of mankind by the goddess Nüwa (see Fig. 2). A few lines later, following the mention of other mythical figures and the sage kings of antiquity, Confucius is respectfully presented as scholar and sage, with his legacy lasting into the present. With this rather learned presentation of the beginnings of Chinese civilisation, the text moves on seamlessly to an extended list of agricultural terms, from farm tools and the natural environment to the various grains. It goes on to introduce how society is organised by listing the terms used for government offices, family relationships, and other subjects.

As with most other vocabulary lists, we do not know the name of the author who composed it. But at the end of the text, he seemed to pause and, stepping back from his role as the purveyor of information, revealed something about himself (see Fig. 3). He noted how he had arduously searched through the classics and canons in the process of compiling the vocabulary list, and how it was simply exhausting: ‘My wrists are sore when I hold the brush; my eyes are dazed when I stare at words’. While he wanted to add still more lines to the little book, he wrote, the expanse of human affairs is endless. Then, as if he remembered something he had forgotten before, he described the vocabulary of funereal rituals, which also serves as a curious reflection on mortality at the end of the book. The following lines conclude the text:

Today I have finally completed the task [of compiling this text];

Now it’s ready to be transmitted to future students.

Do not dismiss this book as cheap and shallow;

Do consider it worth a thousand cash.

Often at the end of vocabulary lists there is an apologia by the author, seemingly self-depreciatory but actually advertising the work. Here the author acknowledged that the educated elite might well frown on his attempt to discourse on history and society. A vocabulary list is hardly a book seen as worthy of ‘a thousand cash’; yet in presenting it as such, the author affirmed that what he had compiled was indeed a valuable and useful tool, a product of excruciating labour worthy to be transmitted to future generations of students.

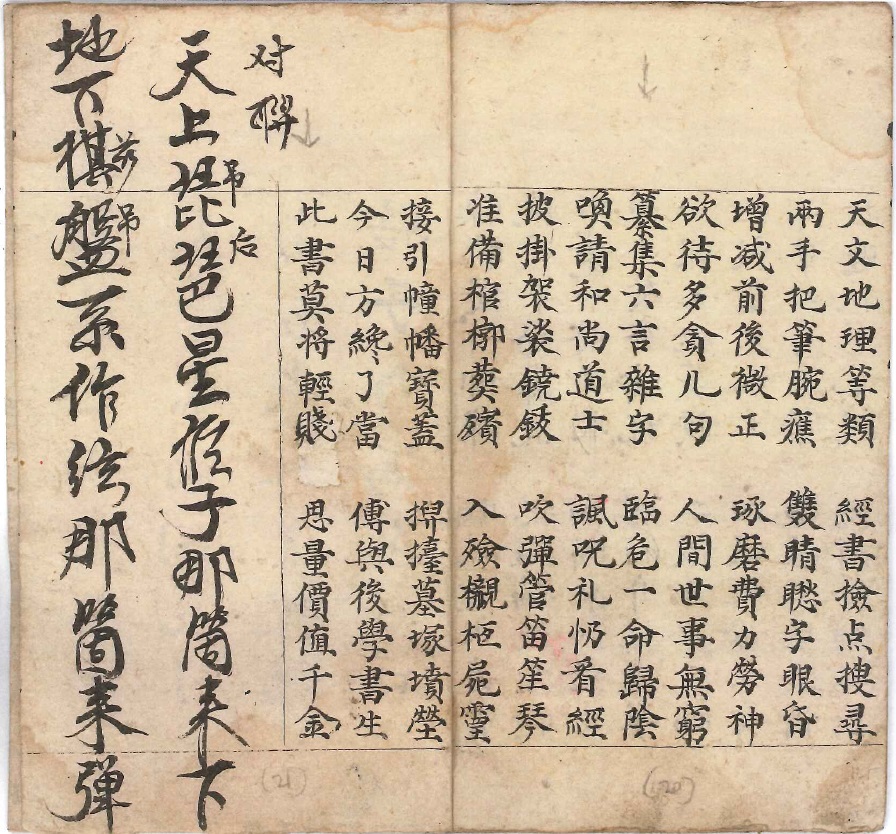

What makes this manuscript so interesting is not only the text itself, but also the marks left behind by those who had come across it. The reader will notice that, on the same page, beyond the final lines of the main text, are two lines written in large bold characters, in a lively ‘running-hand’ (xingshu) calligraphic style in contrast to the careful ‘standard’ (kaishu) style used by the copyist throughout the main text (see fig. 3). These two lines form a duilian, or matching couplet, a set of poetic lines with strict parallel segments, whose composition was an art. Duilian appeared on scrolls decorating rooms and doorways; once they were also the stuff of literary competitions and drinking games. The one here, written in a colloquial style, is a variation of a known couplet, but we do not know who wrote it on the manuscript – perhaps by an advanced pupil in a moment of boredom? Perhaps out of his desire to show off his new mastery of calligraphy?

Whatever the occasion, the order of words got confused in the writing. The calligrapher (or possibly a later reader) seemed to have noticed the errors, and made corresponding ‘editorial notes’ in the form of small letters written to the right of each line, indicating that several characters ought to reverse places. Properly ordered, the couplet ought to read like this:

Heaven is a chessboard and the stars are pieces; who shall move them?

Earth is a lute and its paths are strings; who shall pluck them? *

* Alternatively, these lines can be rendered as: Stars are the pieces on the chessboard up above – who shall move them? / Gossamer are the lute-strings in the world below – who shall pluck them?

References

- BROKAW, Cynthia (2007): Commerce in Culture: The Sibao Book Trade in the Qing and Republican Periods. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center.

- BAI Liming (2005): Shaping the Ideal Child: Children and Their Primers in Late Imperial China. Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press.

- GU Yueqin 顾月琴 (2013): Richang shenghuo bianqian zhong de jiaoyu: Ming Qing shiqi zazi yanjiu 日常生活變遷中的教育: 明清時期雜字研究. Beijing: Guangming ribao chubanshe.

- HASE, Patrick H (2012): “Village Literacy and Scholarship: Village Scholars and their Documents.” In: Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Branch 52, 77-137.

- HAYES, James W (2010): “Manuscript Documents in the Life and Culture of Hong Kong Villagers in Late Imperial China.” In: Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Branch 50, 165-244.

- HAYES, James (1987): “Specialists and Written Materials in the Village World.” In: David Johnson, Andrew J. Nathan, and Evelyn S. Rawski (eds.): Popular Culture in Late Imperial China. Berkeley: University of California Press, 75-111.

- LI Guoqing 李國慶 (ed.) (2009): Zazi leihan 雜字類函. 11 vols. Beijing: Xueyuan chubanshe.

- RAWSKI, Evelyn Sakakida (1979): Education and Popular Literacy in Ch’ing China. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- WU Huifang 吳蕙芳 (2007): Ming Qing yilai minjian shenghuo zhishi de jiangou yu chuandi 明清以來民間生活知識的建構與傳遞. Taipei: Taiwan xuesheng shuju.

- ZHENG Acai 鄭阿財 and ZHU Fengyu 朱鳳玉 (2002): Dunhuang mengshu yanjiu 敦煌蒙書研究. Lanzhou: Gansu jiaoyu chubanshe.

- ZHANG Zhigong 張志公 (1962): Chuantong yuwen jiaoyu chutan 傳統語文教育初探. Shanghai: Shanghai jiaoyu chubanshe.

Description

Manuscript in private collection

Material: Paper, 12 folios with writing on both sides, except for the last folio (writing on recto only), thread-bound, evenly spaced four-hole sewing

Dimensions: 19.68 cm x 12.06 cm

Provenance: China, undated

Reference note

Ronald Suleski, ‘Consider it worth a thousand cash’

In: Wiebke Beyer, Zhenzhen Lu (Eds.): Manuscript of the Month 2016.09, SFB 950: Hamburg,

http://www.csmc.uni-hamburg.de/publications/mom/57-en.html

Text by Ronald Suleski

© for all pictures: Ronald Suleski