No 53

Abbess, Prophetess – and Saint?

Abbess Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179) founded the convent of Rupertsberg in 1150 on a hill of the same name situated at the confluence of the Rhine and Nahe. It was there she wrote various treatises on natural history as well as three volumes recording her visionary experiences. During the first half of the 13th century, a new copy of her third visionary work, Liber divinorum operum (‘Book of Divine Works’), was created at Rupertsberg, featuring ornate gilded miniatures. How did this valuable manuscript of Hildegard’s visionary writings come to be created so long after the abbess’s death?

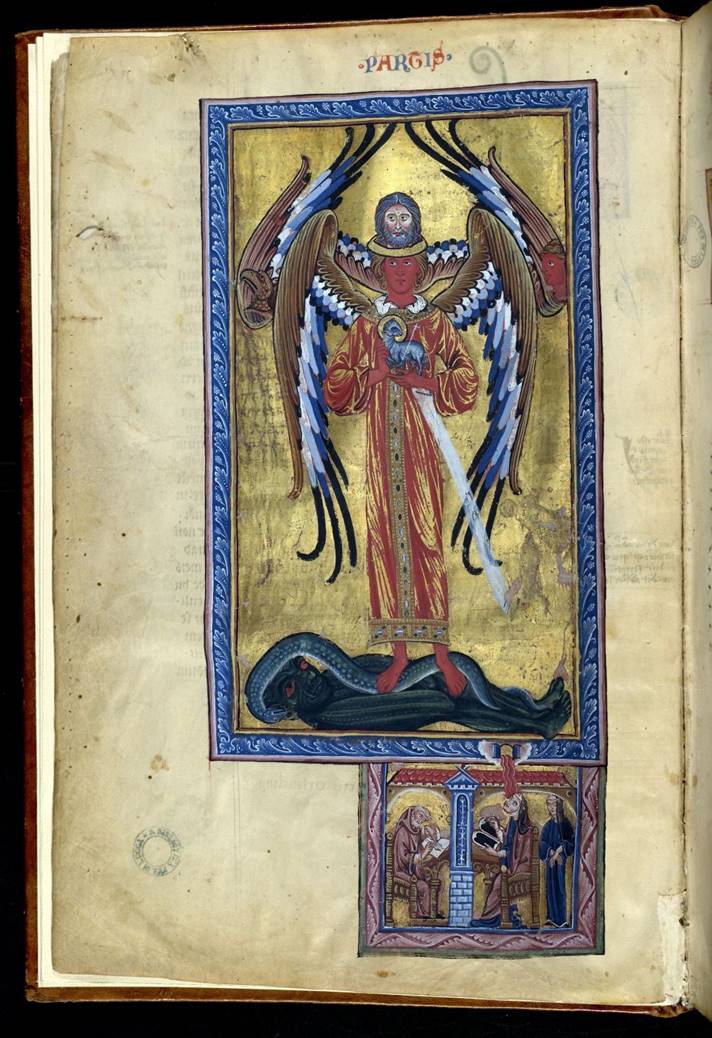

The manuscript contains the full text of Hildegard’s Liber divinorum operum on 164 folios. The folios each measure 39 × 25.5 cm and they are arranged in two columns of 38 lines. Ten folios are decorated with full-page miniatures (see fig. 1). This is the only illustrated manuscript of the Liber divinorum operum.

The codex contains ten of Hildegard’s visions, which are mostly presented in the same basic format: a full-page miniature is followed by a description of the vision and an analysis of its meaning, dictated by a voice from heaven. The visions are framed by a prologue describing the context in which the visions were received and by an epilogue containing a personal message from Hildegard herself.

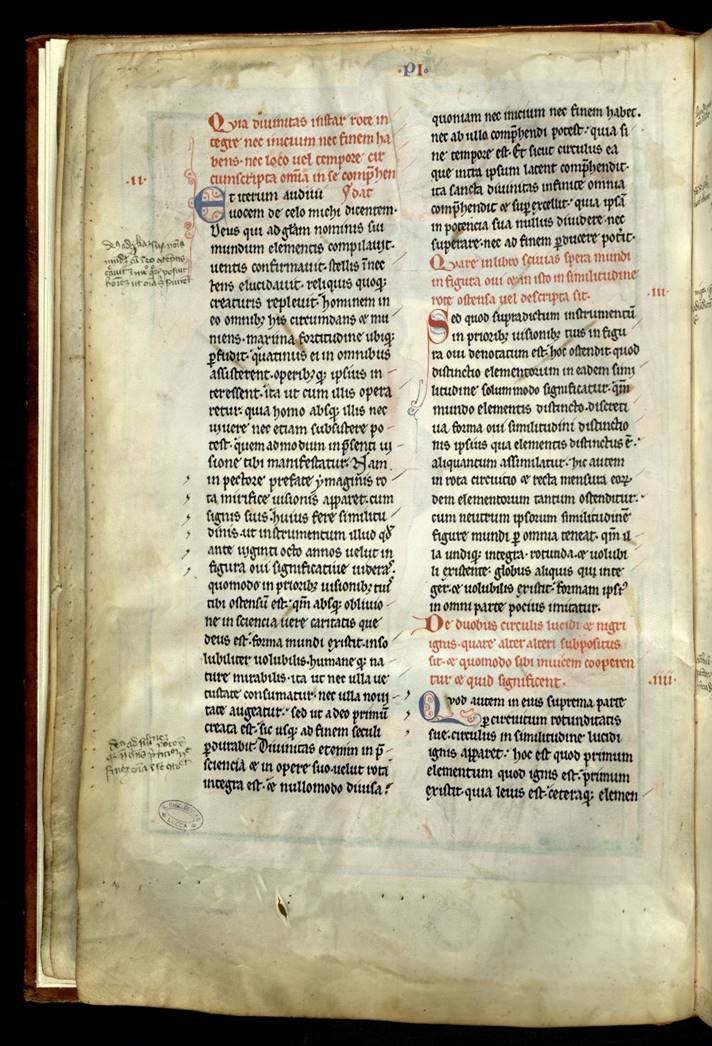

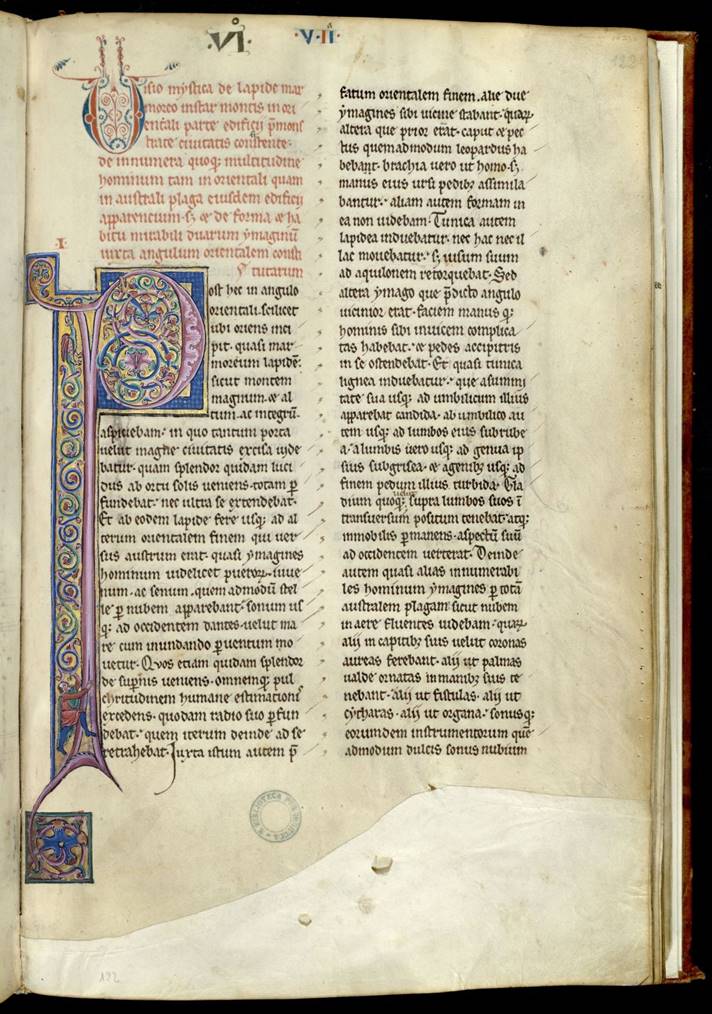

The beginning of the prologue and the start of each of the ten visions are heralded by ornate initials decorated with gold leaf (fig. 2). The visions are divided into several sections, with each section preceded by a brief summary in red ink (fig. 3). There are three parts in the Liber divinorum operum, each featuring a different number of visions.

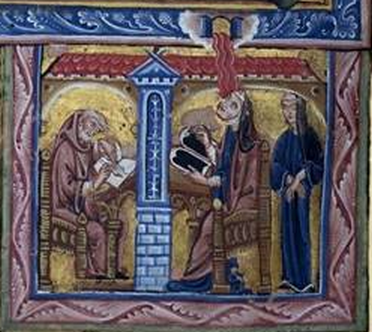

Women in the 12th century were not permitted to write and distribute their own interpretations of the Church’s religious doctrines. Hildegard overcame this hurdle by identifying herself not as the author of the doctrines but as an intermediary – a prophetess, in other words. This role is reflected in the illustrations in the Liber divinorum operum: each of the ten full-page miniatures also features a smaller picture of Hildegard, with the first one in particular showing the divine inspiration (fig. 1 and 4): on the left sits Volmar the monk who, according to the prologue, was witness to the visions (presumably, he assisted Hildegard by correcting the grammar in her writings). The nun who appears on the right is the second witness. Hildegard herself is seated in the centre and is writing on a wax tablet. She is looking upwards at an opening in the frame of the miniature through which a red torrent is streaming down upon her, representing divine inspiration.

This scene is enhanced artistically by the luminous gold background typical of all miniatures: depending on the lighting, the gold leaf can shimmer so intensely that the figures and forms in the illuminations are barely recognisable, similar to Hildegard’s own descriptions in the prologue:

[…] when a true vision of the unfailing light had shown to me, a human being, the diversity of various morals, of which I had been quite ignorant.

Therefore, I, […] have at last turned my trembling hands to writing. As I have done this, I have looked to the true and living light to see what it is I ought to write. (translated by Nathaniel Campbell)

Various marginal notes from the 13th and 14th centuries suggest that the manuscript must have remained in use for a considerable length of time. It is remarkable that such an opulently illuminated manuscript was produced so many years after Hildegard’s death. The creation of the manuscript can presumably be placed in the context of the petition at Rupertsberg Convent for the canonisation of Hildegard, in other words, the act of having her officially included in the canon of recognised saints.

It was against this backdrop in the 13th century that several manuscripts containing works by Hildegard were sent from the convent at Rupertsberg to Rome to be vetted by Pope Gregory IX as part of the canonisation process. It is impossible to say whether this particular manuscript was among those sent, although it is likely to have been produced in the efforts to have Hildegard proclaimed a saint. The text and illustrations in the Liber divinorum operum make the reader a witness to the visions experienced by Hildegard, whose role as a prophetess is conveyed very persuasively. The canonisation process may have stalled in the Middle Ages, but Hildegard was finally declared a Doctor of the Church by Pope Benedict XVI in 2012.

References

- BENZ, Ernst (1969): Die Vision. Erfahrungsformen und Bilderwelt. Stuttgart: Klett.

- BURNETT, Charles / DRONKE, Peter (eds.) (1998): Hildegard of Bingen. The Context of Her Thought and Art. London: Warburg Institute.

- DEROLEZ, Albert / DRONKE, Peter (eds.) (1996): Hildegardis Bingensis, Liber divinorum operum, Turnhout: Brepols.

- DINZELBACHER, Peter (1981): Vision und Visionsliteratur im Mittelalter. Stuttgart: Hiersemann.

- GANZ, David (2008): Medien der Offenbarung. Visionsdarstellungen im Mittelalter. Berlin: Reimer.

- HEIECK, Mechthild (2012), Neuübersetzung aus dem Lateinischen von: Hildegard von Bingen, Das Buch vom Wirken Gottes. Liber divinorum operum, Beuroner Kunstverlag.

- MEIER, Christel (2003): ‘Die Quadratur des Kreises. Die Diagrammatik des 12. Jahrhunderts als symbolische Denk- und Darstellungsform’ in PATSCHOVSKY, Alexander (ed.): Die Bildwelt der Diagramme Joachims von Fiore. Zur Medialität religiös-politischer Programme im Mittelalter. Ostfildern: Thorbecke, 23–54.

- MEIER, Christel (2014): ‘nova verba prophetae. Evaluation und Reproduktion der prophetischen Rede der Bibel im Mittelalter. Eine Skizze’ in MEIER, Christel / WAGNER-EGELHAAF, Martina (eds.): Prophetie und Autorschaft. Charisma, Heilsversprechen und Gefährdung. Berlin: de Gruyter, pp. 71–104.

- RINKE, Stefanie (2006): Das »Genießen Gottes«. Medialität und Geschlechtercodierung bei Bernhard von Clairvaux und Hildegard von Bingen. Freiburg: Rombach.

- SAURMA-JELTSCH, Liselotte E. (1998): Die Miniaturen im »Liber Scivias« der Hildegard von Bingen. Die Wucht der Vision und die Ordnung der Bilder. Wiesbaden: Reichert.

- SUZUKI, Keiko (1998): Bildgewordene Visionen oder Visionserzählungen. Vergleichende Studie über die Visionsdarstellungen in der Rupertsberger „Scivias“- Handschrift und im Luccheser „Liber divinorum operum“-Codex der Hildegard von Bingen. Berne: Lang.

Description

Lucca, Biblioteca Statale

Shelf mark: ms. 1942 (digital scan)

Material: parchment, 167 leaves, contemporary binding

Dimensions: 39 × 25.5 cm

Provenance: Middle Rhine, Rupertsberg (?), first half of the 13th century

Reference note

Karin Becker, “Abbess, Prophetess – and Saint?”

In: Andreas Janke (Ed.): Manuscript of the Month 2016.05, SFB 950: Hamburg,

http://www.csmc.uni-hamburg.de/publications/mom/53-en.html

Text by Karin Becker

© for all pictures: Ministero dei Beni e delle Attività Culturali e del Turismo – Biblioteca Statale di Lucca