No 52

A marriage (contract) to last a lifetime?

Around 4,000 years ago in Central Anatolia, a young man called Kalua, the son of Akabšē, decided to marry Tamnanika, the daughter of Šū-Bēlum. Even at that time, people knew that marriages were not always made to last, so it was agreed that if their marriage did come to an end one day, whoever left the other person first also had to leave them a considerable amount of money. The marriage contract containing the proviso was written on a tablet of clay. This managed to survive the test of time, but the interesting question here is whether the marriage did, too.

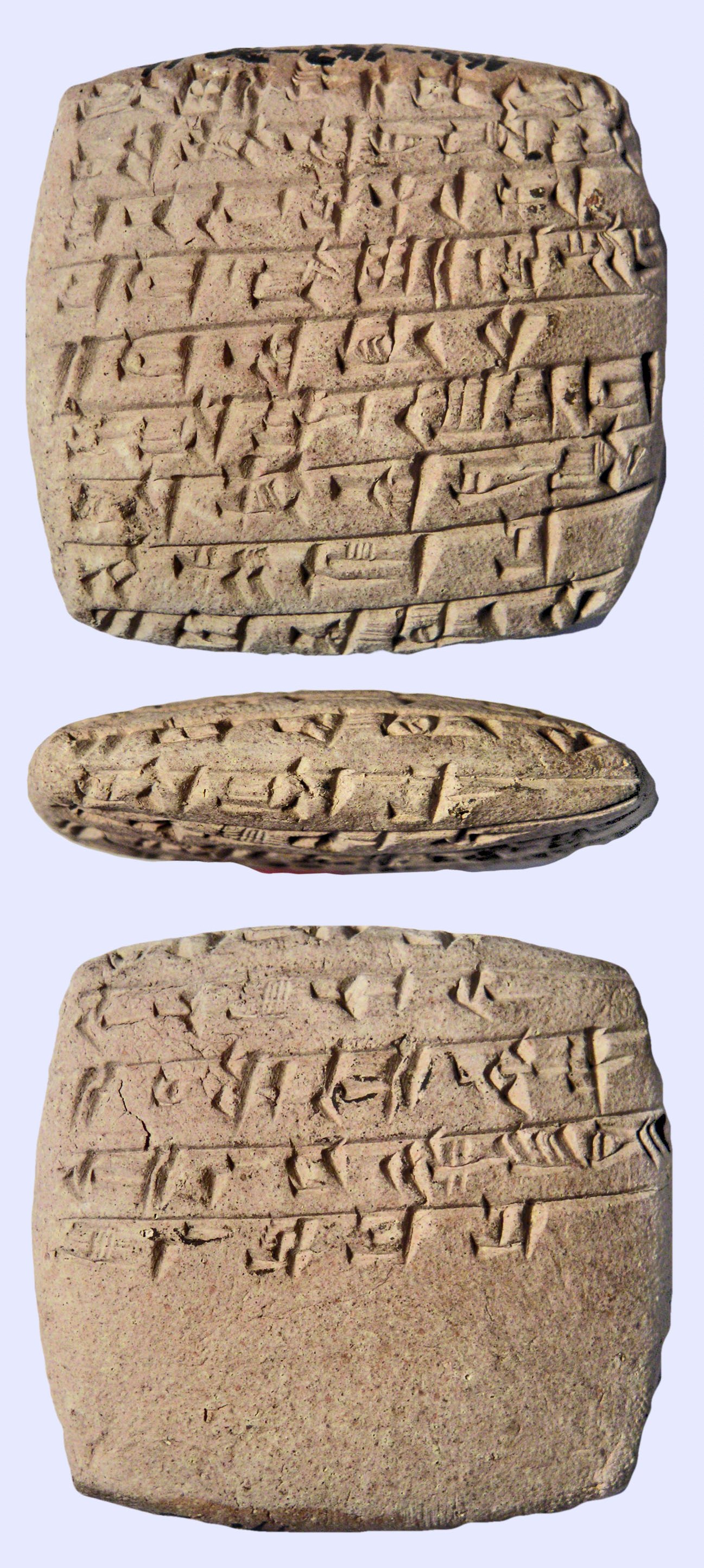

The manuscript in question is an ancient clay tablet and is approximately 4.5 × 4 cm in size (fig. 1). A matching ‘envelope’ goes with it, which is 5.5 × 5 cm and made of a thin layer of clay (fig. 2). This cover was only put over the tablet once the latter had dried completely. The texts seen on the tablet and envelope include a marriage contract written in Akkadian with cuneiform script impressed on the clay. In addition to this, there are also impressions of cylinder seals on the envelope. The manuscript has been dated to the nineteenth century BCE and was discovered in the ruins of a house in Kanesh in 1970 along with more than 200 other clay tablets. Kanesh was an ancient town in Central Anatolia close to what is now the city of Kayseri.

Clay tablets are three-dimensional objects that, unlike paper or parchment, have edges that can each be written on. Due to their form, they were turned around a horizontal axis by the reader, not around a vertical one, which makes them different from paper manuscripts. In other words, the text runs from the front of the tablet to the back of it via the bottom edge (fig. 1).

Assyrian merchants brought the cuneiform script with them at the beginning of the second millennium BCE when they first took their wares with them to trade in Anatolia. The local population gradually made use of the script as well, though not for their own language, but for writing in Akkadian just like the traders did. They do not seem to have mastered this foreign language completely, though, as the things they wrote down often contain spelling mistakes that give researchers clues about who exactly the authors might have been. The text shown here is no exception: it contains some minor grammatical mistakes involving personal pronouns, for example, which a native speaker of Akkadian would have been unlikely to make. Perhaps Kalua even wrote the marriage contract himself.

The bride and groom were from two different ethnic groups, which we can tell by the names of those involved in the ceremony: the groom was Anatolian, while the bride was most likely the daughter of an Anatolian woman and an Assyrian merchant from Assur, a city south of Mosul in present-day Iraq. There were several witnesses to the signing of the marital agreement who are mentioned at the end of the document. Their names indicate they were Anatolian and Assyrian as well.

While the contract documents the marriage of the two people, it also includes a clause on divorce. This says that the one who leaves their partner first is obliged to pay the other person the stately sum of roughly one kilogram of silver. Each person was entitled to the same compensation in this case, but they were also duty-bound to the other person to an equal degree. This means Tamnanika was entitled to leave her husband if she wished to, but if she chose to do that, she had to pay this penalty in return. We also know about the equal standing that spouses enjoyed from other Assyrian documents that have been found. What is unique about this particular document, however, is the final clause it contains, which declares that Kalua is not allowed to treat his wife badly or leave her ‘on bad terms’. The wording on the clay tablet and the envelope for it differs and has been interpreted by researchers in various ways, particularly in view of the closing statement. What is clearly apparent, however, is that the contract favoured the bride.

Besides having a text written on it, the envelope also has a number of cylinder seals on it that have been pressed into the clay. These seals were small, cylindrical objects whose imprint was essentially a kind of printed signature. Various motifs and scenes whose style greatly depended on the time and place they were made are depicted on the seals. A total of six different seals can be identified on the envelope, which will have belonged to Kalua and the witnesses. By pressing their seals onto the envelope around the clay tablet, the witnesses confirmed they were present when the marriage contract was signed and thus made the contract a legally binding document. The bridegroom’s seal was proof that he agreed to the terms of the contract. This manuscript was probably kept in some kind of archive belonging to the bride’s own family after the ceremony. Although no copies of the original document have been found so far, it still seems reasonable to assume that the groom and possibly each of the witnesses received one.

A list at the beginning of the text on the envelope mentions the names of those who pressed their seals onto it, but the seals themselves bear no writing whatsoever and the impressions they left on the clay have none on them either. This is why it is no longer possible to attribute them to a particular individual. The motifs they contain tell us that the people involved probably belonged to various ethnic groups. The seal shown in figure 3 contains an ‘introductory scene’ in which a human being is being introduced to a sitting god by a lower deity. The various gods are recognisable by the horned crowns they are wearing. Besides these figures, there are also two bull-people and another figure standing behind the sitting god. Scenes of this kind were typical for the Mesopotamian region and are known to have existed since the end of the third millennium.

Like other documents of a legal nature, contracts such as the one here were kept in clay ‘envelopes’ that were sealed. Breaking this protective casing and thus the seal around the opening symbolised the annulment of the document’s legal validity. When archaeologists discovered Kalua and Tamnanika’s marital agreement, it was still protected by its envelope, which had been closed and sealed. Apparently, the agreement was never broken and the marriage lasted the test of time after all.

References

- DONBAZ, Veysel (2003): ‘Lamniš ulā ezebši “He shall not leave her in a bad situation (wickedly)”’, in G. J. Selz (ed.), Festschrift für Burkhart Kienast zu seinem 70. Geburtstag dargebracht von Freunden, Schülern und Kollegen, AOAT 274, Münster: Ugarit-Verlag, 47–50.

- KIENAST, Burkhart (2015): Das altassyrische Eherecht. Eine Urkundenlehre. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- MICHEL, Cécile (1998): ‘Quelques réflexions sur les archives récentes de Kültepe’, in Sedat Alp / Aygül Süel (eds.): International Congress for Hittitology III. Uluslaraɪ 3. Hititoloji Kongresi Bildirileri, Ҫorum 1996, 419–433.

- MICHEL, Cécile (2010): ‘Presentation of an Old Assyrian Document’, in Fikri Kulakoğlu / Selmin Kangal (eds.): Anatolia’s Prologue, Kültepe Kanesh Karum, Assyrians in Istanbul, Istanbul: Kayseri Metropolitan Municipality, 98–99.

- VEENHOF, Klaas R. (1998): ‘Two Marriage Documents from Kültepe’, in Archivum Anatolicum, 3, 357–381.

Description

Location: Museum of Anatolian Civilisations, Ankara

Excavation no.: kt v/k 147

Material: clay

Dimensions: tablet: 4.3 × 4.1 × 1.5 cm; envelope: 5.5 × 5 × 5.6 cm

Provenance: 19th century BCE, Kanesh (in present-day Turkey)

Reference note

Wiebke Beyer, “A marriage (contract) to last a lifetime?”

In: Andreas Janke (Ed.): Manuscript of the Month 2016.04, SFB 950: Hamburg,

http://www.csmc.uni-hamburg.de/publications/mom/52-en.html

Text by Cécile Michel

© for all pictures: Kültepe Archaeological Mission; photographs: Cécile Michel