No 37

A Hybrid Talismanic Manuscript

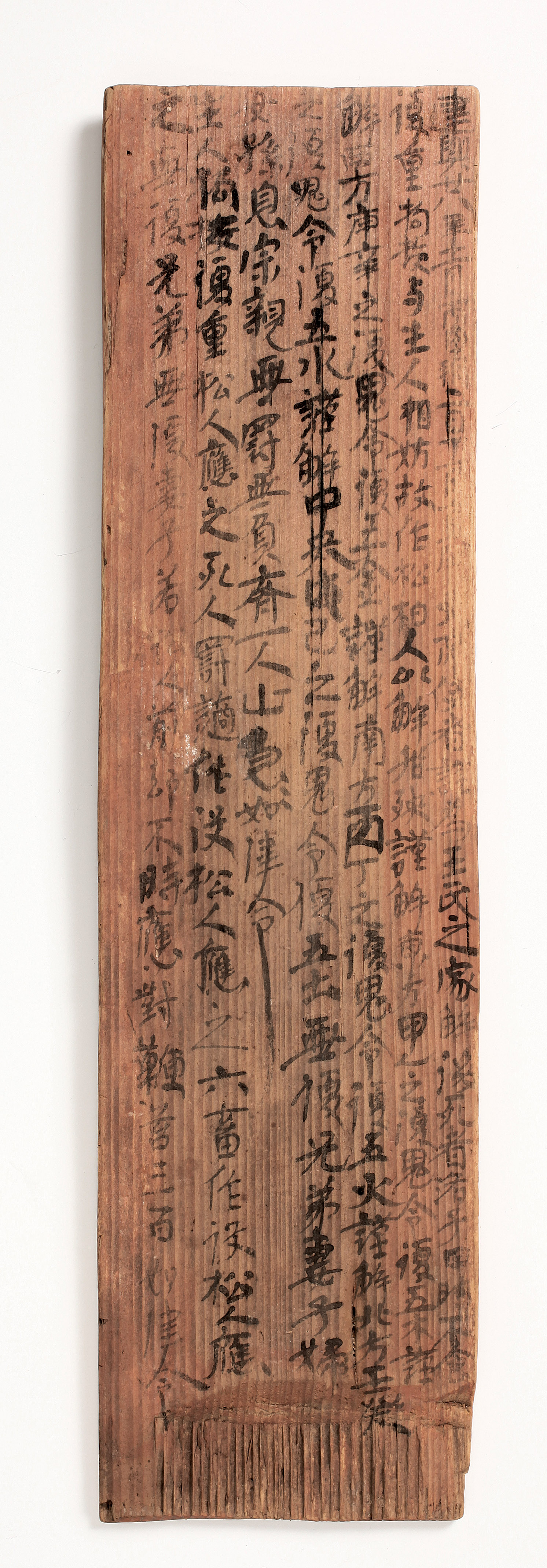

The 340 CE "Pine Man" Wooden Tablet

Stern-faced, a mustached man stands solemnly with forearms raised in front of his chest. The posture reveals an apron-like wide belt with long tassels at about the abdomen level, on which two characters curiously read “Pine Man” (songren 松人). The writing draws the viewer’s attention towards the figure’s otherwise plain long robe. What is even more intriguing, however, is where the Pine Man appears: on a rectangular wooden tablet fully inscribed with texts in black ink. Who is he? Why is he on a wooden tablet?

The outline of the “Pine Man,” which occupies the top two-thirds of the tablet’s front (see fig. 1), was first carved out in a slightly raised form, clearly discernible in the side-view (see fig. 2). The details were then drawn in black ink. Except for the area that the “Pine Man” figure occupies, the tablet was once completely painted in reddish pigment, now long faded. In black ink, a quick hand wrote three short single-line texts in large characters and one section of densely composed longer text in smaller characters around the “Pine Man.” On the back (see fig. 3), the same hand covered the entire surface with an even longer text in large characters. The texts make it clear that this inscribed wooden tablet with the “Pine Man” on it was made for the occasion of the death of a man named Wang Xi 王屖, also known as Luozi 洛子, in 340 CE. But why and for what purpose?

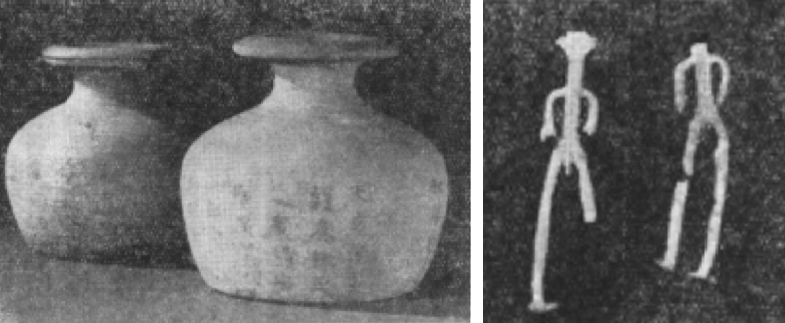

By the second century CE, it was widely believed in China that there was an underworld register of everyone, alive and dead. Accordingly an underworld bureaucracy recorded detailed information about a person’s birth and death, including the exact year, month, day, hour, and constellation alignment, and regularly reviewed these records. A person would only die when his or her assigned lifespan expired. However, clerical mistakes and bureaucratic mishaps were also seen as inevitable and common in such record keeping. A death like Luozi’s was not just a single tragedy for the bereaved family but was likely to trigger a chain of misfortune if no special care was taken to ensure the safety of the dead in the afterlife and the protection of the living in this world. One paramount measure was to seek assistance, from a higher celestial authority, usually mediated through a ritual specialist, to check and guarantee the accuracy of the records kept by its subordinate underworld bureaucracy. Subsequently a written document – a celestial ordinance closely resembling official communications in its language and format – was buried to accompany the deceased to the afterlife, in which separating the dead and the living and releasing both parties from future hardship and misfortune were especially articulated. In addition to this one-time appeal at the time of death, provisions for both subsistence and comfort of the deceased in the afterlife were also buried. These occasionally included human-shape lead figurines. Two such “substitute lead humans” (zidai qianren 自代鉛人) were found in a ceramic pot in a 147 CE tomb, who were described in the accompanying written ordinance as “quick and fast...capable of pounding rice and cooking, driving a chariot, and writing with a brush.” Two other “lead humans” found in another second-century CE tomb were meant to “release the deceased from blame and eliminate offenses and wrongdoings of the living,” as the ordinance stated (see fig.4).

The two longer texts on the “Pine Man” wooden tablet closely resemble the above-mentioned celestial ordinances found on burial pottery jars. Both were written in the voice of a certain Envoy of the Heavenly Thearch (tiandi shizhe 天帝使者), on behalf of the highest authority of the celestial realm, addressing the underworld on the occasion of Luozi’s death. Both texts begin with the date when the ordinance was issued, the second day of the eleventh month in 340 CE, and end with the formulaic expression adapted from official communications, “according to the statutes and ordinances” (ru lüling, 如律令). However, the two texts differ in their respective focus: the one underneath the “Pine Man” on the front is largely concerned with the safety of the deceased Luozi, while the longer one on the back is primarily concerned with the well-being of his surviving family. What they have in common is the designated role of the “Pine Man” and a now lost “Cypress Man” (bairen 柏人) to protect both the dead and the living under dangerous circumstances after Luozi’s death. Pine and cypress wood were believed to have apotropaic powers. Therefore, the “Pine Man” and the “Cypress Man” were expected to respond to potential threats from various sources and take upon themselves both the blame and the punishment meted out to the dead or the living. Compared to Luozi’s protected afterlife and his surviving family’s further life after Luozi’s death, the fate of the “Pine Man” may not be desirable, but it is inescapable. One of the single-line short texts reads: “Between Heaven and Earth [i.e., under all circumstances], when checking and correcting the underworld register, if there is an overlap [i.e., another death], the Pine and Cypress men shall bear it.” The long ordinance text on the back ends with an even more forceful command: “If the Pine Man retreats from such misfortunes and does not speedily respond to and face them, beat him with a whip three hundred times, according to the statutes and ordinances.”

It has become clear that the “Pine Man” was meant to function similarly to those “substitute lead humans.” The difference lies in that the “Pine Man” was drawn on a wooden tablet and not represented as a three-dimensional figurine. Bamboo and wood were the most common writing material before paper became ubiquitous in the fifth century CE in China. The “Pine Man” tablet is a hybrid talisman, combining textual ordinances and an apotropaic “Pine Man” image for the benefit of both the dead and the living in one object. It is the first known example of such hybridity. As an object acquired from the antique market, its unknown provenance hinders a precise understanding of the intended ritual context and conditions of its discovery. However, thanks to its rich content and our recently expanded repertoire of knowledge about death-related beliefs and practices in ancient China, it is now possible to re-situate this peculiar tablet in a wide range of what can be called talismanic objects of its time and re-imagine their production and functions.

References

- CHEN Songchang 陳松長 (2001): “Jindai ‘Songren’ jiechu mudu” 晉代《松人》解除木牘. In: Xianggang zhongwen daxue wenwu guan cang jiandu 香港中文大學文物館藏簡牘. Hong Kong: Xianggang zhongwen daxue wenwu guan, 109-113.

- SHAANXI WENWU GUANLI WEIYUANHUI 陝西文物管理委員會 (1958): “Chang'an xian Sanli cun Donghan muzang fajue jianbao” 長安縣三里村東漢墓葬發掘簡報. In: Wenwu cankao ziliao 文物參考資料 7, 62-65.

- HENAN SHENG BOWUGUAN 河南省博物館 (1975): “Lingbao Zhangwan Hanmu” 靈寶張灣漢墓. In: Wenwu 文物 11, 75-93.

Description

Art Museum, the Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China

Material: wood (species unknown), red pigments, black ink

Dimensions: 35.8 cm x 9.4 cm x 0.8-1.2 cm

Provenance: unknown

Date: ca. 340 CE

Text by Guo Jue

© for fig. 1-3: Art Museum at the Chinese University of Hong Kong