No 28

A letter incarnate?

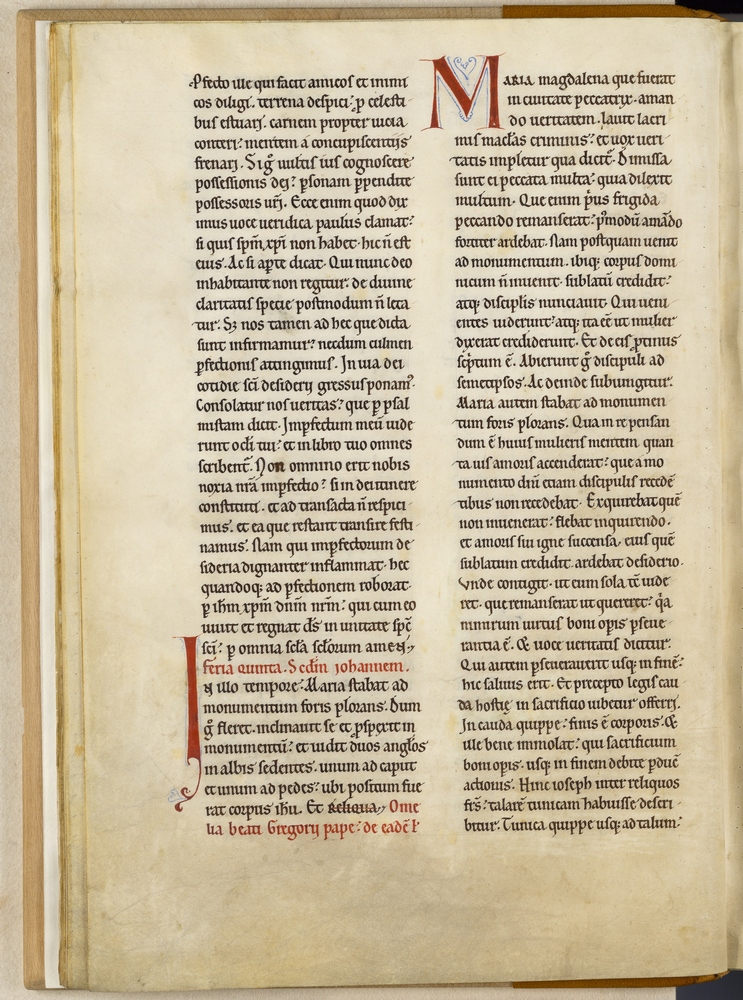

Held by the Hamburg State and University Library and bearing a venerable text dating from the 8th century, albeit originating more than 300 years later from the scriptorium of a monastery in Cologne, this medieval manuscript contains only one character represented by something other than a conventional letter of the alphabet. The character itself serves instead as the backdrop to a human figure and is almost entirely concealed by it. It is the first letter of the first word in the book as a whole. Who is this person and why is he gazing at the viewer so searchingly?

The codex, which was executed some years either before or after the turn of the 13th century at the famous monastery of St. Pantaleon in Cologne, came very close to destruction in common with a group of manuscripts held by the Hamburg State Library, including the Manuscript of the Month, August 2012, which was produced at the same scriptorium.

The manuscript contains a homilary consisting of sermon texts (homilies), which were only read on Sundays and principal holy days within clerical circles. The individual sermons always begin with a quotation from the Bible, followed by an exegesis or a commentary by one of the Fathers of the Church.

This collection of sermons may be ascribed to the scholar Paulus Diaconus (Paul the Deacon), who in the late 8th century was commissioned by Charlemagne to compile a collection of homilies taken from the writings of the Church Fathers. The texts were to be bound in two volumes. The first volume, known as the pars hiemalis (‘winter part’), contained sermons for the period from Advent to Easter Sunday, whereas the second volume, the pars aestival (‘summer part’), encompassed sermons for the period from Easter Sunday until the end of the church year.

t was said to have been the most famous collection of sermons of the Middle Ages!

The value that was placed on the text, even some 300 years later, is evidenced by the external appearance of the manuscript:

The size of the codex alone, 51 centimetres high and 25 centimetres wide, bears clear testimony to the precious nature of this object. When one considers that, in order to produce a double folio of parchment of these dimensions, the full pelt of a slaughtered animal would need to be used, it becomes evident just what material value was accorded to the surface of the manuscript alone. Moreover, the high quality of the parchment with its light, even coloration and immaculate surface is quite astonishing.

Preparatory work had to be undertaken on a piece of parchment in order to achieve a uniform surface for writing. To this end, a network of lines was drawn over each folio, being either traced in dark-coloured ink or indented with a stylus. In the case of this manuscript, the ruling marks, which achieved the pronounced appearance of the text, allowing it to appear to hover just above the surface of the parchment, can only be seen with a trained eye. The writing itself is clean and distinct, with few mistakes. Like most large-format manuscripts, the text is divided into two columns in order to aid the eye – in this case of the celebrant of the Mass – when read aloud.

The codex featured here is the second part of what was once a two-volume work, and thus begins with a sermon for Easter Sunday. It is not known when the first volume went missing.

When the reader opens the manuscript at the homily for Easter Sunday, his gaze is immediately drawn to a figure who returns his look in a watchful manner (fig. 1). The figure represents Christ, as is evident from the yellow-gold cruciform nimbus encompassing his head. This is the sole figural representation in the entire volume. Christ holds his right hand before his chest in a gesture of benediction, whilst his left hand encircles the end of a banner, on which the following quotation from the Bible appears in Latin (Matthew 28:18; see fig. 2): “Data est mihi omnis potestas in caelo et in terra” (“All power is given unto me in heaven and in earth”). Christ utters this phrase to his disciples following the Resurrection. He goes on to command them to go out into the world and to proclaim the Gospel. The figure of Christ stands before the letter and almost entirely obscures it. Thus, it is closely connected with the character, emulating its shape as an enlarged capital letter, which stands at the start of the first passage from the Bible. The figure echoes the shape of the letter “I” as it appears in “in illo tempore”, an introductory phrase frequently occurring in the Bible, which means “in that time, …”. The following Biblical text (Mark 16:1–2), which in common with every sermon in this manuscript is introduced by a rubric in red, describes in a few words how the women discovered Christ’s empty tomb. Thus, the theme here is mankind’s first sight of the miracle of the Resurrection. In this manner, the women standing startled and dismayed at the empty tomb are linked to the figure of Christ, who in his turn, however, gazes at the viewer, exhorting him to live according to the Gospel and to proclaim it. In effect, the women do not see Jesus, but the reader of the volume witnesses the Risen Christ, becomes cognisant of the Mystery and receives Christ’s commission.

When one looks at the page again, one is struck by the next large initial that occurs after a further red rubric, similar to the one that stood at the start of the first passage. Entwined with scroll ornament, it prefaces the commentary originally written by Gregory the Great, a 6th-century Doctor of the Church. What is evident is that precisely the same colours are employed here as are used for the initial letter decorated with the figure of Christ. Only the gold of the nimbus is not re-used for the second capital letter, since it is a symbol of the divinity of Christ and thus appropriate only to that figure. Otherwise, the hues employed for Christ’s blue and red garments and the green of the framing appear again in this initial letter.

It occurs to the viewer that Christ is also present here at the start of the next passage of text in the use of the identical palette. This also applies to the beginning of other homilies, which retain the same red and blue hues despite their simpler initial characters (fig. 3). In this manner, Christ is painted – and kept in mind – at the start of every sermon, the Christian message being announced in the coloration alone!

The interweaving of letter and figure of Christ ultimately suggests the Christian notion of the incarnated logos, the word of God made flesh in Christ. Here the incarnated word has become a letter made flesh that is evoked at the start of every homily, thus completely permeating the ancient, highly esteemed text, letter for letter.

References

- BRANDIS, Tilo (1972): Die Codices in scrinio der Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Hamburg. Hamburg: Hauswedell, 25–26.

- LEGNER, Anton (ed.) (1985): Ornamenta Ecclesiae. Kunst und Künstler der Romanik, catalogue of exhibits at the Schnütgen Museum, Cologne, vol. 2, 291.

- LEGNER, Anton (ed.) (1972): Rhein und Maas. Kunst und Kultur 800-1400, catalogue of exhibits at the Schnütgen Museum, Cologne, vol. 2, 321, 330.

- STORK, Hans-Walter (2005): “Handschriften aus dem Kölner Pantaleonskloster in Hamburg. Beobachtungen zu Text und künstlerischer Ausstattung”, in H. Finger (ed.): Mittelalterliche Handschriften der Kölner Dombibliothek (Erstes Symposion der Diözesan- und Dombibliothek Köln zu den Dom-Manuskripten). Erzbischöfliche Diözesan- und Dombibliothek: Cologne, 259–285, esp. 237.

- SCHMITZ, Wolfgang (1985): “Die mittelalterliche Bibliotheksgeschichte Kölns”, in A. Legner (ed.): Ornamenta Ecclesiae. Kunst und Künstler der Romanik, catalogue of exhibits at the Schnütgen Museum, Cologne, vol. 2, 137–148.

- WIEGAND, Friedrich (1897): Das Homiliarium Karls des Großen auf seine ursprüngliche Gestalt hin untersucht. Leipzig: Deichert.

Description

Hamburg, Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek

Shelf mark: Cod. in scrin. 1b

Material: parchment, 174 leaves

Dimensions: 51.5 x 35 cm, modern foliation

Written space: 40.5 x 25 cm, 2 cols., 38 lines, large Gothic minuscule

Place of origin: Cologne, St. Pantaleon’s Monastery, between 1190 and 1210

Text by Lena Sommer

© for all images: State and University Library Carl von Ossietzky, Hamburg.