No 26

Creativity on the manuscript page:

William Wordsworth’s Diaries Notebook (DC MS 19)

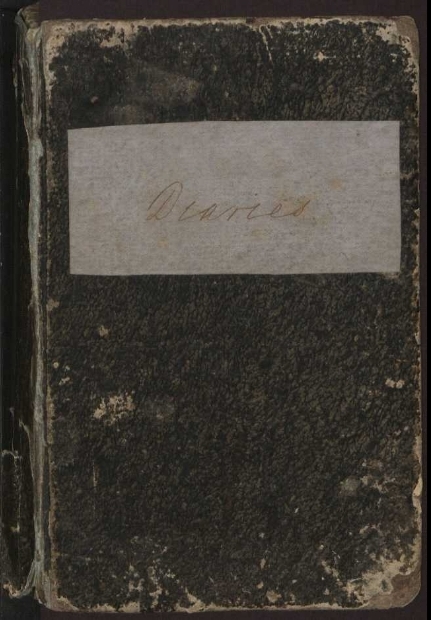

Unprepossessing and tattered from use, the small, black-covered notebook which contains the earliest known version of William Wordsworth (1770-1850) great autobiographical poem The Prelude is a manuscript that speaks to the imagination. One of the prized treasures of The Wordsworth Museum at Dove Cottage, Grasmere (DC MS 19), the notebook was a cheap, ordinary, ephemeral affair; and despite being designated “Diaries”, written on a paper label on the front cover, its original intended use was to be merely practical. So why was it so significant that it was worth preserving?

We know the exact circumstances in which Wordsworth acquired the notebook. It was purchased, with four others just like it, from a stationers shop in Bristol for just 1 shilling, when the poet and his sister Dorothy were preparing for an extended tour of Germany in 1798-99 in the company of their friend S. T. Coleridge. Coleridge had masterminded the tour. He wanted “to meet scientists, theologians, and moral philosophers” and eventually ended up by himself in Göttingen, Germany’s intellectual centre in the eighteenth century, while Dorothy and William Wordsworth settled down for 5 months in Goslar, the historic town in the Harz Mountains. They had heard Goslar was cheap, but the secluded, rough, mountainous region would have reminded Wordsworth too of his native Cumberland.

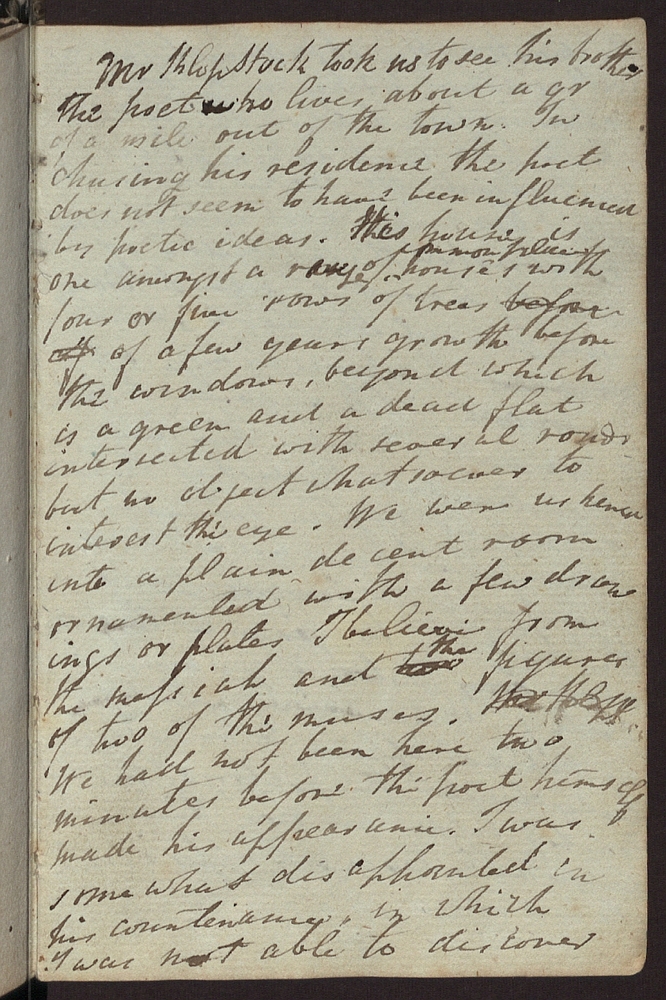

The Diaries Notebook is much more than a personal journal: it contains the “record” of their German sojourn. It opens with an account, written by Dorothy, of the siblings’ rather strenuous journey to Hamburg, where they had landed from England on 19 September. Having practically no German, and with little money to spare, their stay in the city was far from pleasant: Dorothy complains bitterly about rude landlords and shopkeepers who took advantage of the fact that they were foreigners and over-charged for food and accommodation.

While in Hamburg, Wordsworth visited the great poet Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock on no less than three occasions (twice with Coleridge in tow). They conversed in French about the history of German poetry, blank verse, Rousseau, Kant, Schiller and Wieland; yet, as the notes reveal that he hurriedly set down in DC MS 19, Wordsworth seemed most intent on pressing him for his views on the great English poets. But Klopstock, it transpired to Wordsworth’s disappointment, did not know much about English poetry, and Wordsworth was not a little dismayed when Klopstock preferred Richard Glover over John Milton.

After Coleridge had gone his separate way, the Wordsworths moved to Goslar, where they arrived on 6 October. The winter of 1798-99 was a particularly cold one, and with few acquaintances around, they led a quiet, fairly isolated existence. There was little to do but to work indoors. Brother and sister started learning German, diligently recording German vocabulary in the Diaries Notebook. William complained about the lack of access to books. Inadvertently this made him more productive. Much of the thinking and writing that he did during this period ended up in DC MS 19.

The notebook thus not only served for general note-taking and the recording of experiences. For William in particular it became a place for reflection. He began to compose an “Essay on Morals” in which he purports to know of no system of moral philosophy that has the “power to melt in our affection[?s]” and that is therefore able to influence our habits and actions. Not a great advocate of systems of thought, however, Wordsworth appears not to have finished the piece. The essay breaks off mid-sentence and is followed by 5 leaves which were torn out of the notebook. Nonetheless, this philosophical fragment is evidence of Wordsworth’s intellectual preoccupations which the notebook captures. One can surmise that the poet’s mind during this lonely, productive winter was turning towards the great project of his life (which was also his single greatest failure) – a colossal philosophical poem to be called The Recluse.

The poem was to be an investigation of “my most interesting feelings concerning Man, Nature, and Society”. But in order to tackle this subject with insight, he needed to understand the origins of it, which he thought – at 28 years of age – lay in the history and growth of his own mind. What was to become one of the greatest poems from the Romantic period, The Prelude was on the one hand, as Wordsworth called it, an antechamber to the greater work, and on the other a delving into origins.

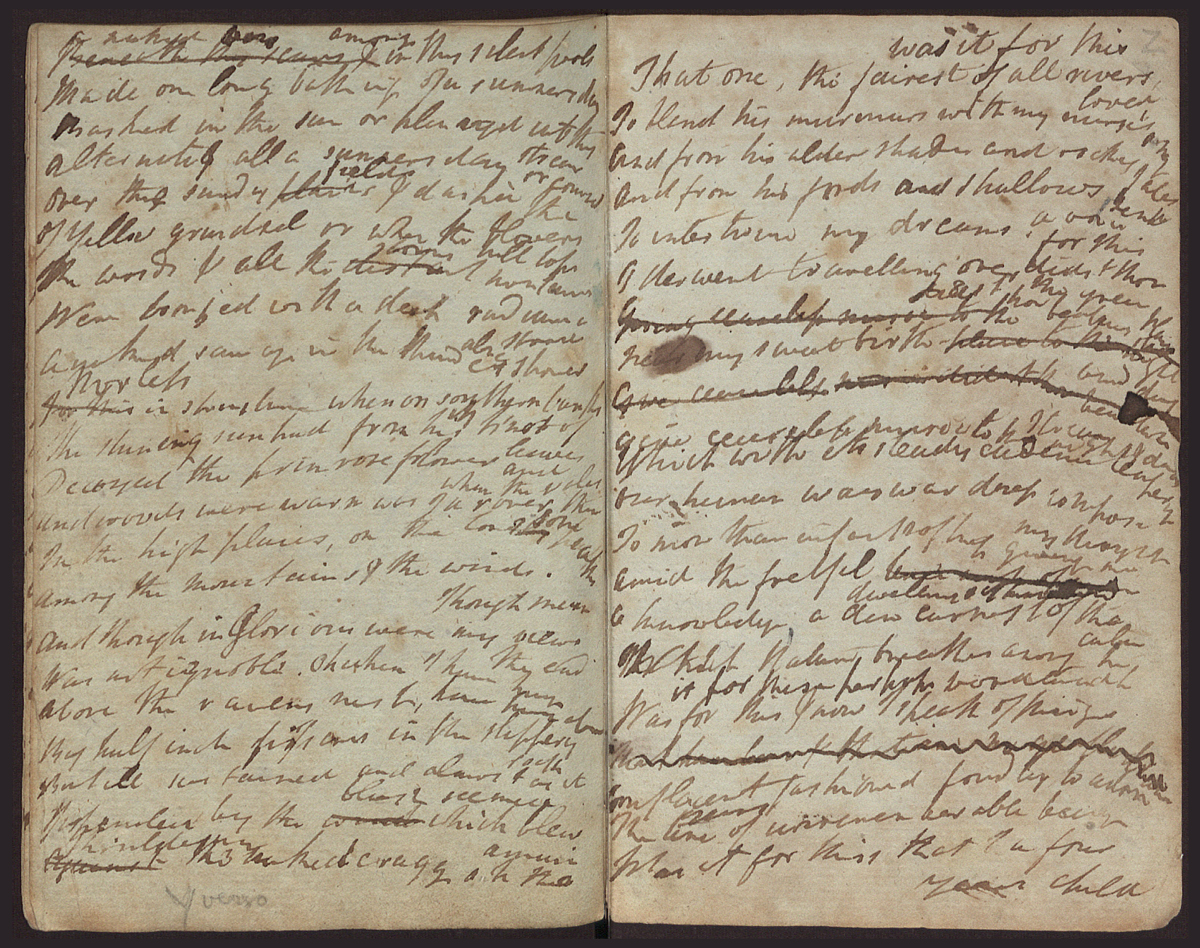

In an almost careless hand, Wordsworth wrote down the lines “was it for this | That one, the fairest of all rivers, loved | To blend his murmurs with my nurse’s song” in the back of his notebook. This alone practically ensured that the Diaries Notebook was preserved for posterity. The origins of the poem itself are quite humble: a jumble of poetic fragments that suddenly erupt towards the back of the notebook, written at different moments and in different moods of inspiration.

Scholars have generally taken the view that Wordsworth inscribed the poem backwards, starting with “was it for this” on the last page of the notebook. But this view is not entirely sustained by the evidence in the manuscript, nor is it wholly compatible with the writing practices of other poets. The handwriting is really heavily variable: sometimes it is small, measured and legible, tending towards lines that were copied fair from elsewhere; sometimes it is the opposite — rough, blotted, nearly illegible. Even when the hand is in between it reveals unmistakably the vestiges of the hand trying to keep up with the mind. The physical evidence points to a very fragmentary procedure.

The manuscript, in others words, puts into relief the lofty notions of inspiration propagated by the Romantic poets. Several accounts describe Wordsworth’s habit of composition in which he composed his poems while walking up and down the lane outside his house, or sometimes even on horseback. This is no obfuscation. But the state of the earliest draft of The Prelude, as well as many of the poet’s other manuscripts, demonstrates that Wordsworth did not transfer his poems whole from mind to paper. He needed the page to write, to try and to err.

There is a touching coda to the story of the Diaries Notebook. After returning to England in May 1799, William and Dorothy settled down in Dove Cottage, in Grasmere in the heart of the Lake District. In 1802 she started up her journal again, using the empty pages of DC MS 19. This journal, covering the period 14 February to 2 May. This recycling of an “old” notebook points to its utility rather than its veneration. Yet from then on the manuscript became inherently connected with the location celebrated in Dorothy’s journal. The furthest it travelled was less than 50 km to Carlisle, where William Wordsworth, the poet’s son, resided when he inherited the notebook as part of the family papers in 1851; Graham Gordon Wordsworth, the grandson, brought the papers back to Ambleside, just down the road from Grasmere. He bequeathed them in 1935 to the Wordsworth Trust which set up a Museum in the village, where notebook DC MS 19 is still one of the centre pieces of the collections.

References

- COWTON, Jeff and BUSHEL, Sally (eds.) (n.d.): From Goslar to Grasmere—William Wordsworth: Electronic Manuscripts. [accessed on 23 May 2014].

- PARRISH, Stephen (ed.) (1982) The Cornell Wordsworth. The Prelude, 1798-1799. Cornell: Cornell University Press.

- OWEN, W.J.B. and SMYSER, J. W. (eds.) (1974) The Prose Works of William Wordsworth. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- VAN MIERLO, Wim (2013): “The Archaeology of the Manuscript: Towards Modern Palaeography”. In: Carrie Smithand Lisa Stead (eds.): The Boundaries of the Literary Archive: Reclamation and Representation. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate, 15-29.

- WOOF, Pamela (ed.) (2002): The Grasmere and Alfoxden Journals of Dorothy Wordsworth. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Description

Present Holder: The Wordsworth Trust, Grasmere, United Kingdom

Shelfmark: DC MS 19

Material: Small notebook bound in black boards; originally 96 leaves in gatherings of 16, 7 leaves have been torn out, with stubs remaining. Watermark consists of the words PRO PATRIA, a large crest and oval circle, with two warriors. Decent quality laid paper with chain lines 2.5cm apart.

Dimensions: c. 9.5 x 15 cm

Provenance: United Kingdom, 1798-1802. Bequest of Gordon Graham Wordsworth, 1935.

Text by Wim Van Mierlo

©: All images are reproduced by kind permission of The Wordsworth Trust, Grasmere.