No 10

Jesus’ wife: A papyrus adrift

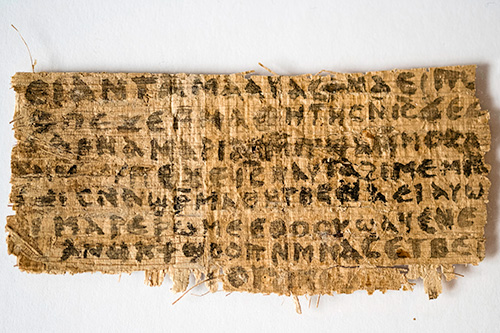

'Harvard scholar's discovery suggests Jesus had a wife'. This was the heading under which Fox News reported on a presentation given on Tuesday evening, 18 September, by Karen L. King during the 10th 10th International Congress of Coptic Studies studies at the Institutum Patristicum Augustinianum, only a few meters away from Vatican City. Coverage in the European and Italian media over the following days was of similar tenor, but with variations of tone and critical understanding, as well as barely pertinent references to Dan Brown's The Da Vinci Code. The news can be quickly summed up. In the course of the conference the scholar presented a fragment of a papyrus which bears sentences, in Coptic translation, from a dialogue between Jesus and his disciples about a woman, Mary, whom he describes as 'his wife' (ta-hime / ta-shime, which in Coptic corresponds to 'woman' or 'wife'). There is nothing unusual about this for a scientific conference. However, in this case, the excessively direct link between research and journalism – that makes short shrift of the extended research periods required by more serious scientific discussion – had already occurred before the conference. The premature coverage in the American press on Tuesday was based on an interview that the Harvard academic had already given before she left for Italy.

While the media were describing the outlines of the discovery in tones which in some cases are quick to shock, causing a sudden interest in the Congress of Coptic Studies, King published a draft of a powerful article about this fragment of papyrus and its content, which she wrote in collaboration with other young scholars, on her university’s website. The article will not appear in the Proceedings of the Congress (intended to appear no earlier than January 2015), but has been submitted to the Harvard Theological Review and, if it passes the peer review process, will be published next January. Thus, the article exhibits all the features of scientific objectivity, as was to be expected from Karen L. King, a renowned scholar of Gnosticism and gender issues in early Christianity. The key conclusions are as follows: It is an ancient fragment, dating from the fourth century; the Greek text that is the basis of the Coptic translation is even older, probably composed around the second century; it is testament to the existence of environments in which the marriage of Jesus was debated: “The fragment does provide direct evidence that claims about Jesus’ marital status first arose over a century after the death of Jesus in the context of intra-Christian controversies over sexuality, marriage, and discipleship”, King writes.

I would like to say in advance that I have reservations regarding this point of King’s argument. But there is more: I think that it is precisely this argument which opened the way her discovery was reported in the media, where sentences expressing the intimacy and spiritual consubstantiality between the Saviour and his disciples, usual in Gnostic texts, were turned into an affirmation of Jesus’ alleged marriage. This issue, even if it cannot be accepted as an historical fact of Jesus’ life on the basis of this text, was, according to King, something that was discussed among Christians of the second century when they talked about Jesus and sexuality.

When faced with an object of this kind which, unlike so many items presented at the conference, was not discovered during an excavation, but came from the antiques market, a number of precautions are necessary in order to establish its reliability and exclude the possibility of forgery. First, it must be studied in its materiality: From what kind of manuscript could it come? How does palaeographic research date it? Secondly, what kind of text is it? In which literary context does Jesus’ baffling statement take place? What meaning does the statement take in this specific context? It must be said that there are many problems on both levels of research (into the papyrus and the text). King admits that some colleagues have questioned the authenticity of the papyrus, while other papyrologists have expressed a more favourable evaluation. A number of coptologists present in Rome during the conference, expressed doubts about the authenticity based on the photograph which was shown on Fox News and appeared in some newspapers (these include Stephen Emmel, Wolf-Peter Funk, Alin Suciu, Tito Orlandi, Paola Buzi). At the same time, they reserved the right to revise their opinion after they have had access to more detailed information. They observed both the character of the fragment, which makes it difficult to recover the type of manuscript from which it comes (literary codex? amulet?), and the characteristics of the writing, which appear to differ from most of the known models of the fourth century and a vast number of later models. It has been suggested that the characters of the Coptic fragment are a clumsy reproduction of printed Coptic characters.

On the one hand, of course, the peculiarity of an object does not make it a forgery and new findings often differ from the known types. On the other hand, it is the task of the scientific community to assess whether the original hand is modern or ancient, in other words, to give an account of the specific nature of this writing, which appears very different to known models, such as the Nag Hammadi codices, and also quite different to the codices which King used for comparison.

This will direct further research in one of two different directions, and this decision will obviously affect the final judgment on the text. In other words, the manuscript is either a modern forgery, which would render any further investigation meaningless, or it was produced not as a literary text, but as a text intended for internal or private use, as was often the case, for example, with manuscripts produced in the workshops of late antiquity magicians. The latter may have used known texts, especially of Gnostic character, to produce a new, in their eyes particularly effective text in the same way in which their colleagues constructed magical texts by assembling Scriptural passages. If this were the case, the significance of the fragment would be greatly reduced.

But let us look at the text, which is presented as a dialogue between Jesus, his disciples, and a woman. The picture is familiar to those who know the apocryphal literature or the dialogues of resurrection. Especially in the Pistis Sophia, in the Gospel of Mary, in the Gospel of Thomas, and in the Gospel of Philip we find the most relevant parallels, well detected by King. Women appear to be disciples ready to acknowledge a spiritual consonance with the Saviour and one of them, Mary Magdalene, the figure of the true Gnostic, is called the “consort” of Jesus (in the Gospel of Philip, the Greek koinonòs and Coptic hôtre are used, covering the area of semantics that goes from “companion” to “spouse”).

However, the real task is to find out whether the celibacy of Jesus was never doubted or debated in the early Christian tradition, Gnosticism included. The earliest Christian texts do not say anything of a possible marriage of Jesus, even when Mary Magdalene is mentioned. And in the second century the pagan philosopher Celsus, in his radical critique of Christianity (preserved fragmentarily by Origen), recorded slanderous rumours about Jesus’ mother and her extramarital affairs. However, this text contains no information whatsoever about Jesus’ marital status. I, for one, would deem this silence, inside and outside the Christian tradition, more significant than a literal interpretation of a few words in this newly discovered text, which in my opinion should be read purely symbolically.

Draft Paper by Karen L. King

“Jesus said to them, ‘My wife…’” A New Coptic Gospel Papyrus

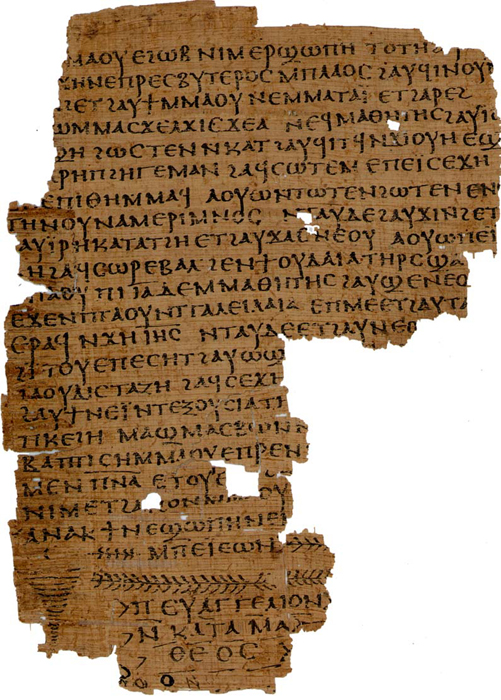

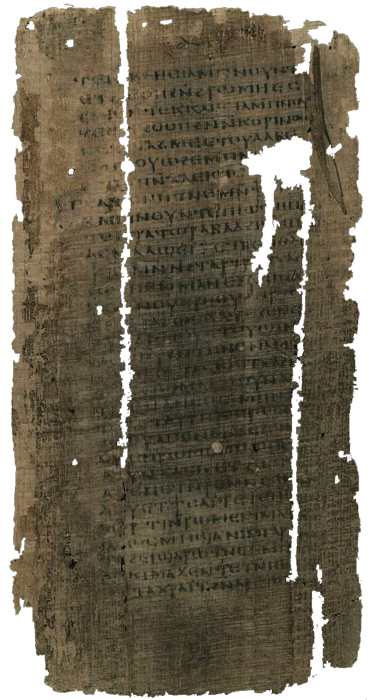

Papyrus codices used for comparison

Ms. or. fol. 3065. Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Orientabteilung (Fig.2)

The Schøyen Collection MS 2650, The Schoyen Collection, Oslo and London (Fig. 3)

Codex Tchacos (Gospel of Judas, p. 37) (Project website "The Lost Gospel of Judas" maintained by the National Geographic Society)

Text by Alberto Camplani

About the author

Alberto Camplani is associate professor of Christianity and Ecclesiastical History at La Sapienza, University of Rome at the Department of History, Cultures, Religions (since 2005) and lecturer at the Institutum Patristicum Augustinianum. From 1990 to 1999 he worked as Technical Researcher for Computer Science Applications to the Humanities at La Sapienza and has been involved in the activities of the “Corpus dei Manoscritti Copti Letterari” (CMCL), as well as in those of the “Centro Interdipartimentale di Servizio per l’Automazione nelle Discipline Umanistiche” (CISADU), directed by Tito Orlandi. From 1999 to 2004 he was assistant professor of Egyptology and Coptic Civilization at La Sapienza.

His research fields are: Literature and History of Christianity and Gnosticism in Egypt and Syria-Mesopotamia in Late Antiquity. He is a member of the research group “Origen and the Alexandrian tradition” and of the International Association for Coptic Studies. He was member of its board for the period 2008-2012. He is Vicedirector of Adamantius, Journal of the Italian Research Group on “Origen and the Alexandrian tradition”. From 2009 to 2012 he headed up the journal Studi e Materiali di Storia delle Religioni. From 2006 to 2008 he coordinated the local unit (Rome) of the PRIN (Research Project of National Interest) “Christianity and the Mediterranean world: diversity, cohabitation and religious conflicts between cities and suburbs (I-VIII century) ”, and also, for the period 2008-2010, the same local unit of the PRIN entitled “The contribution of Christianity to the construction of forms and structures of community (I-IX Century) until the beginning of the first formation of Europe”. He has been Congress Secretary of the Tenth Internationl Congress of Coptic Studies, Rome 17-22 September, 2012.