Buddhist Amulets in Ancient Uighur Language

Yukiyo Kasai

Amulets have a long tradition in many cultures. These objects are handmade and generally small; they are said to have magical powers that bring the wearer protection and good luck. The fragmentary scroll with the shelfmark ВФ-4203 is not itself an amulet; nevertheless, it is an exceptional example of the use of such objects and their distribution across cultural boundaries. What was the purpose of this manuscript and how did it originate?

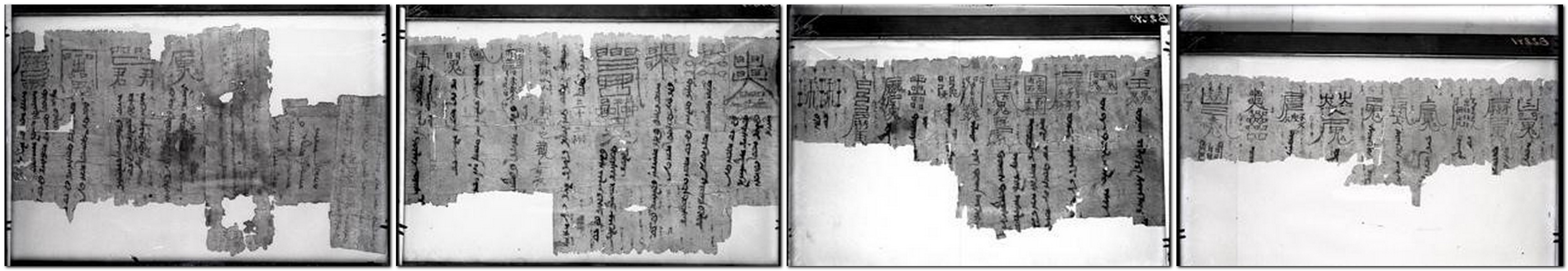

In the Museum of Asian Art in Berlin, there are only four individual photos of the scroll; they have the inventory numbers B 2288–2291 (Fig. 1). The scroll was part of the local Turfan collection, which consists of the finds of the Prussian archaeological expeditions in Central Asia (1902–1914). The scroll’s original excavation inventory number, T II Y 51, indicates that it was discovered in Yarhoto in Turfan (the present-day Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of the People’s Republic of China). After the Second World War, the manuscript was long considered to have been lost. However, thanks to the collaboration of German and Russian scholars, it was rediscovered in the Hermitage in St. Petersburg in 2016. The scroll is kept there under the shelfmark ВФ-4203.

The manuscript is a fragmentary paper scroll measuring 192.6 cm × 29.8 cm. The front side contains amulets, mostly accompanied by Chinese characters, and includes short explanations in Old Uyghur, written in the vertical Uyghur script. The use of Old Uyghur and the Uyghur script suggests that the scroll was written between the 10th and 14th centuries, when both the Old Uyghur language and script were in use.

The amulets do not refer to any single theme such as the healing of diseases, rather, they cover a wide range of areas, such as protection against encounters with evil spirits, false accusations, the difficult birth of a child, or protection for people born in a certain season. Nor are the amulets ordered in any discernible way. And, although the Old Uyghur notes mention the effects of the amulets, they do not explain how they were used in practice.

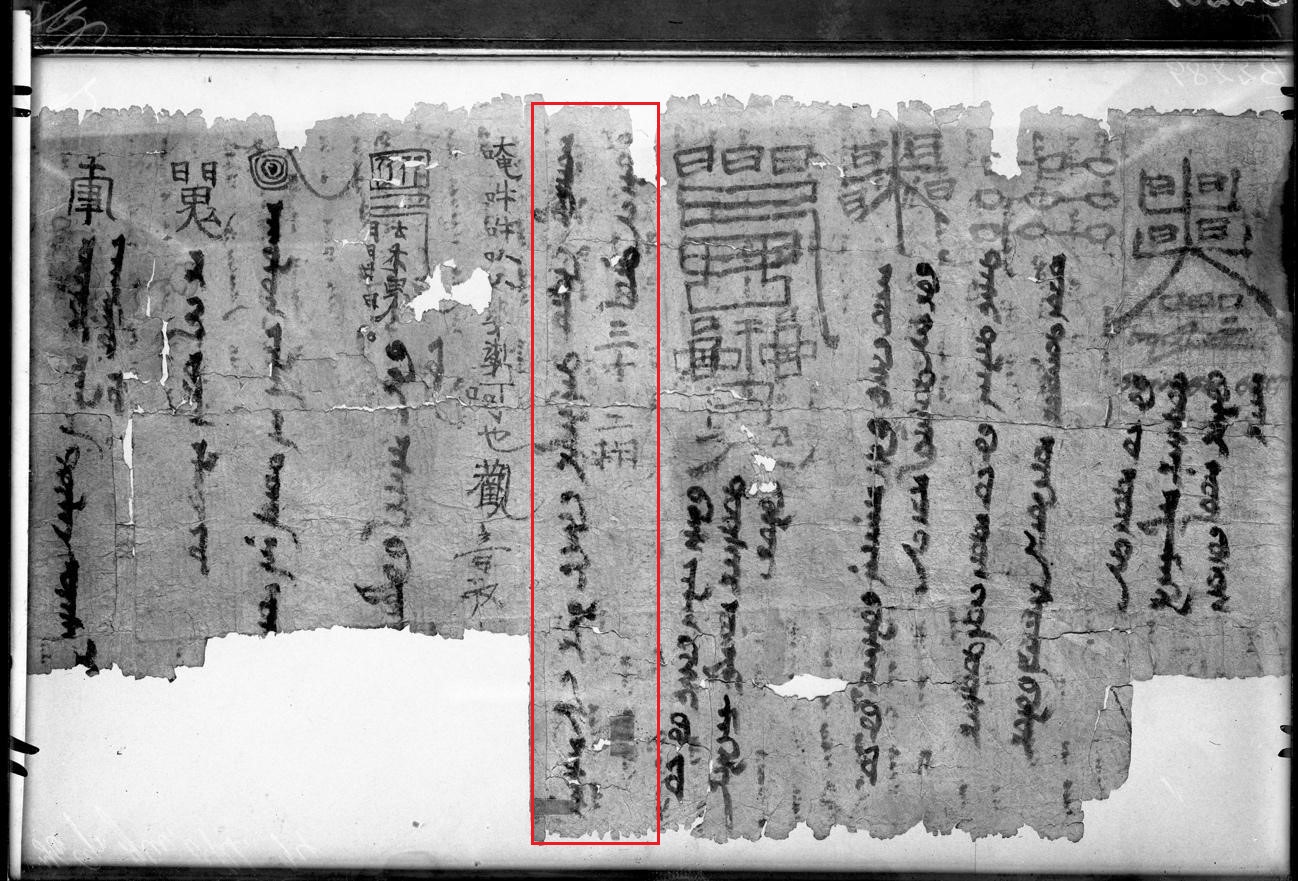

In the middle of the scroll under discussion we find a note (see Fig. 2):

“I, Konımdu, have written this with devotion so that it may benefit those who come later.”

Since the handwriting of this sentence differs slightly from the rest of the text, it might have been added later. Although we know that Konımdu once held the scroll in his hands, we do not know whether he wrote the whole text. In fact, we know nothing about him, his status or his life, but his name indicates the context in which the scroll should be placed. The name Konımdu comes from Chinese Guanyin nu 観音奴 and means “slave of Guanyin”. Since Guanyin is the name of a bodhisattva, the name Konımdu clearly indicates a connection to the Buddhist faith. But how did the Uyghur Buddhists use these amulets? And where did they obtain the amulets with Chinese characters in this scroll?

The use of amulets is widespread in Buddhist culture. It is believed that, with their powers, a wish, for example that of a child or a safe birth, could be fulfilled in the not too distant future or at least during the lifetime of the person expressing that wish. To accomplish this, a suitable amulet is selected, and its image is often drawn on a piece of paper. For the artefact to become effective, it must be worn on the body, hung up in a building, or burned and its ashes ingested with liquid. The Uyghurs probably used similar practises. Although most of the Uyghurs who live in the Turfan area today are Muslims, from the second half of the 10th century (or the beginning of the 11th century) until the 14th century, most of them were Buddhists. During this time, they left written artefacts and art objects testifying to their Buddhist practices in the Turfan area. This scroll is one of these objects.

In general, depictions of amulets are extremely rare in Old Uyghur texts, which lends even more importance to this scroll. The exact origin of the individual amulets is unknown, but, given the presence of Chinese characters they were most likely copied from a Chinese model.

For Uyghur Buddhists, Chinese Buddhism was their primary source, and most Old Uyghur Buddhist texts were translated from Chinese. The Chinese Buddhists of Dunhuang, an oasis not far from Turfan, had a special position here, because the Uyghurs maintained a close relationship with them and adopted many of their ideas and practices; the use of amulets is also documented in Dunhuang. One text is noteworthy here; it is known under the title Foshuo qiqian fo shenfu jing 佛說七千佛神符經 [Sūtra of the Divine Talismans of the Seven Thousand Buddhas, preached by the Buddha], and seven manuscripts of this text have been found in Dunhuang (Or. 8210/S. 2708, Or. 8210/S. 4524, P. 2153, P. 2558, P. 2723, P. 3022 recto, P. tib. 2207), a fact which suggests that it was widely circulated. In view of the lack of earlier mentions, it can be assumed that it originated in the 7th century.

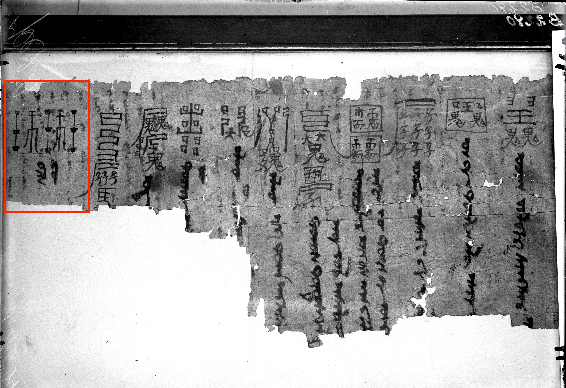

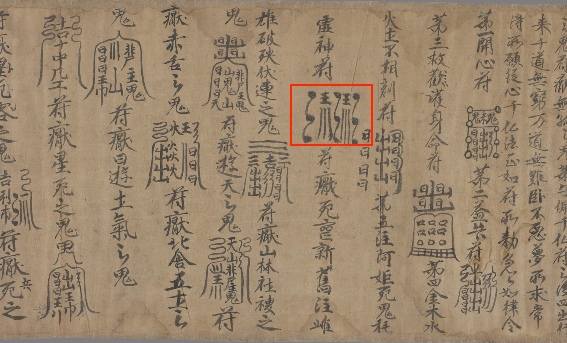

The text first discusses the kinds of protection the Buddhas provide for humankind in general and mentions specific misfortunes such as curses. This is followed by a short description of the numbered amulets, which are shown with a title at the end of the text. Such details are not found in the Old Uyghur scroll, which simply contains images of the amulets and brief notes concerning their effects. However, some images of the Chinese text can also be found in the Uyghur scroll. One such example is the amulet which protects human life against the murderous demons known as Aji (阿姬) and against decrepitude (see Figs. 3 and 4). In the Old Uyghur scroll, the explanation of the amulet is not completely preserved, only the two words beš “five” – corresponding to the numbering in the Chinese original – and vu “amulet” can be read. However, the amulet itself has the same shape as those found in the manuscripts from Dunhuang.

However, only a small number of the amulets listed in the Old Uyghur scroll are mentioned in this Chinese text. The origins of most other amulets remain unclear. Thus, our scroll lacks any detailed explanations of individual amulets, and contains no exact copies or translations of any known Chinese text. It can therefore be assumed that various amulets were collected from different sources and were compiled in this manuscript. With the help of this scroll, its owner could quickly find and use a suitable amulet. That was probably the purpose of this scroll.

The scroll is an excellent example of how Uyghur Buddhists selected ideas from various sources as needed and how they construed and practised their Buddhist culture.

References

Kasai, Yukiyo (2021), ‘Talismans Used by the Uyghur Buddhists and Their Relationship with the Chinese Tradition’, Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 44: 527–556.

Knüppel, Michael (2013), Alttürkische Handschriften. Teil 17: Heilkundliche, volksreligiöse und Ritualtexte, Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 197–199, No. 250–253.

Pchelin, Nikolai and Simone-Christiane Raschmann (2016), ‘Turfan Manuscripts in the State Hermitage–A Rediscovery’, Written Monuments of the Orient 2: 3–43.

Rachmati, Gabdul Rasid (1936), Türkische Turfan-Texte VII, Berlin: Akademie der Wissenschaften, 37–38.

Zieme, Peter (2005), Magische Texte des uigurischen Buddhismus. Berliner Turfantexte XXIII, Turnhout: Brepols, 179–185.

Description

Location: Hermitage Museum (old photographs from the Museum of Asian Art, Berlin)

Shelfmark: ВФ-4203 (original excavation inventory number: T II Y 51)

Material: ink on paper

Size: 192.6 cm x 29.8 cm

Origin: between 11th and 14th century, Yarhoto (according to the excavation inventory number)

Copyright Notice

Copyright of photographs: Museum of Asian Art, Berlin (B 2288 and 2290) and Bibliothèque Nationale de France (P. tib. 2207)

Reference Note

Yukiyo Kasai, Buddhist Amulets in Ancient Uighur Language. In Leah Mascia, Thies Staack (eds): Artefact of the Month No. 29, CSMC, Hamburg.