A Scribe in Training

The First Manuscript of a Twelve-year-old Student of Arabic

Cornelius Berthold

Writing a large book by hand was still a common practise in the Middle East of the early twentieth century. Particularly in traditional schools, pupils might be required to copy by hand the text that was currently being taught. Many of these manuscripts were probably not preserved, and the question arises as to how one would identify the work of a teenager. A note in an Arabic manuscript now kept at the Göttingen University Library (Cod. Ms. Arab. 552) claims that the book was written by a twelve-year-old. But is this true? And to what extent does it differ from manuscripts written by adults?

Niedersächsische Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Göttingen

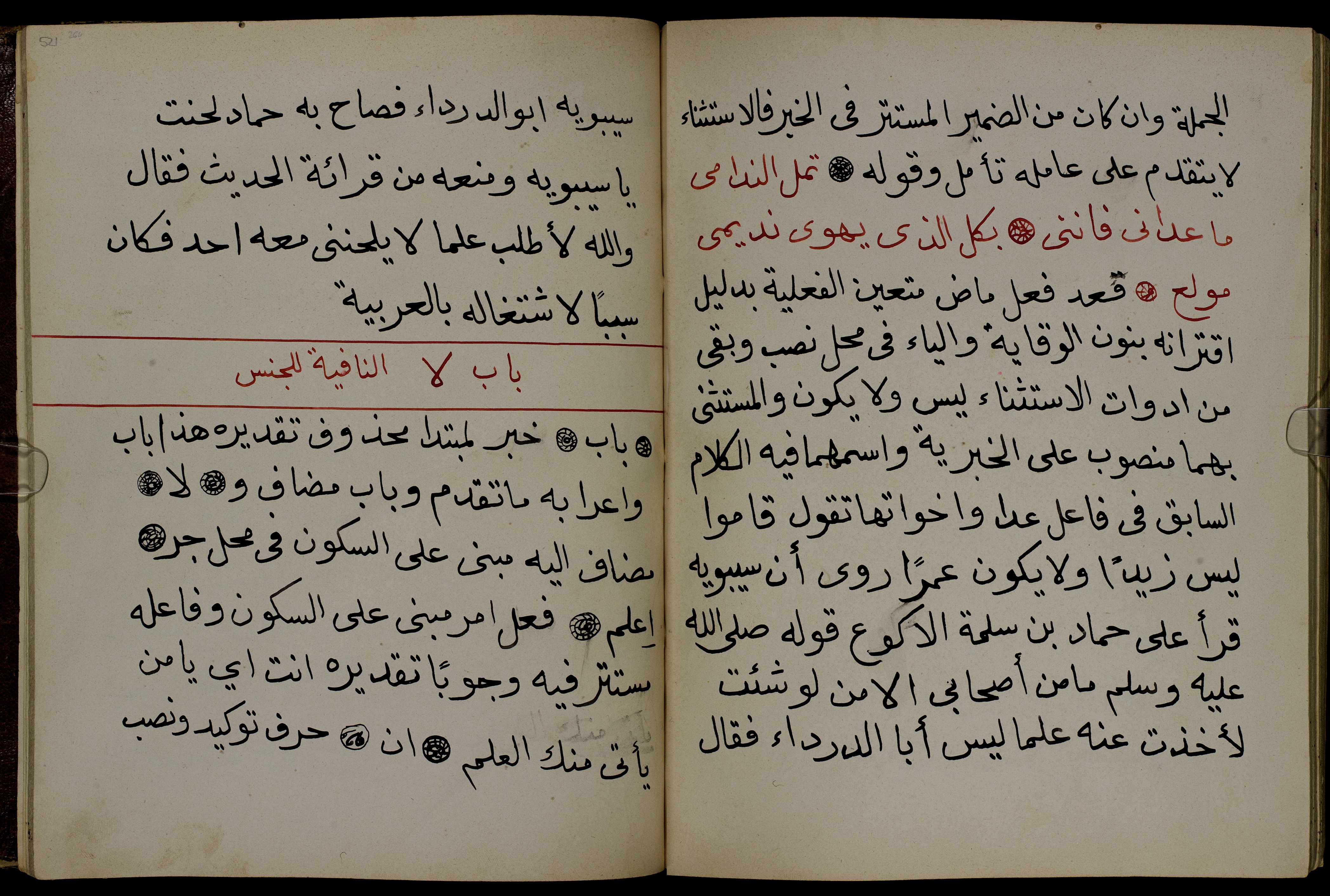

In 1901, the twelve-year-old Muḥammad b. Bakrī al-Ḥakīm b. ʿIzz al-Dīn finished copying a text on Arabic grammar onto a manuscript of 292 folia (or 584 pages). This almost certainly happened in the Middle East, but, unfortunately, we do not know the exact location. At first glance, the manuscript he wrote – Cod. Ms. arab. 552 in the Niedersächsische Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Göttingen (Fig. 1) – is a typical example of its time. With a page size of 23 × 18 cm, the codex is the same size as countless others, and its content is not exceptional, either. The text Muḥammad had written was a copy of a relatively recent commentary on a much older but very famous grammar book, the so-called Ājurrūmiyya, named after its original author, the Moroccan Ibn Ājurrūm (d. 1323). Arabic grammar and lexicography, as well as rhetoric and philosophy were fundamental parts of traditional education in Muslim communities; such texts were taught so that the student could learn how to form arguments and to debate definitions. Making a copy of such a text for oneself was very common at the time, and, in 1901, even copying an entire book by hand was nothing out of the ordinary. Although typography, the art of letterpress printing, had been practised by Europeans for centuries, it was rather difficult to adapt to Arabic script with its overlapping and stacked letters. Muḥammad finished his copy only a couple of decades after typography had gained a permanent foothold in the Islamic world.

Muḥammad b. Bakrī was most likely a pupil in one of the traditional Middle Eastern schools, where students listened to their teachers reading and explaining certain educational texts. The students made copies of these texts for themselves, either from hearing or from reading an older copy. Many manuscripts made in this context must have survived until today, but the objects themselves rarely show any explicit evidence of their origins. With Cod. Ms. arab. 552, the situation is much clearer. On one of the empty leaves (fol. 2r), before the main text begins, there are three funnel-shaped ‘clusters’ of text (see Fig. 2). The topmost, presumably written shortly after the manuscript was completed, mentions the name of the author and the title of the work contained in the codex. The two lower clusters appear to have been written much later. The one on the right states: ‘Written with the pen of the poor shaykh Muḥammad b. al-Shaykh Bakrī al-Ḥakīm, and it was the beginning of his education (kāna awwal taʿlīmihī)’. Such modesty was traditional when scribes in the Islamic world mentioned their own names, but not when they mentioned others; this suggests that this text – and the one on the lower left, which is even more interesting – were indeed written by Muḥammad b. Bakrī himself. The entry on the left translates as follows:

Niedersächsische Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Göttingen

In order to know whether these claims are true, we have to look at the manuscript’s main text. While the two lower additions on fol. 2r were clearly written by Muḥammad after he had become a proficient scribe, his original commentary on the Ājurrūmiyya looks very different. The somewhat crude illumination at the beginning of the text (Fig. 1) is followed by clean and simple writing in naskh script, the most common Arabic bookhand in the Middle East; however, the letters are much larger than in most other Arabic manuscripts (this does not apply to large decorative elements such as calligraphic headings which, of course, do exist). These large and carefully written – or perhaps ‘drawn’ – characters look very much like the work of a child. The number of lines per page varies especially at the beginning of the codex; sometimes only seven lines can be found on a page. Later, when the script becomes more regular and smaller, there are twelve or thirteen lines to a page, suggesting that the handwriting gradually matured. Nevertheless, the writing still lacks a regular flow and remains larger than the handwriting of a professional scribe. Evidently, Muhammad did not use a misṭara, the traditional ruling frame with which one could impress blind lines onto the paper to help the scribe write. This explains why the pages have different numbers of lines and why some of the writing is lopsided. Occasionally, his text was corrected or completed by a different hand, perhaps by a teacher or an older student or by Muhammad himself, later in life. The beginning of the text on fol. 3v, for example, has been added by a more skilled hand, presumably as a model for our twelve-year-old scribe to follow. On the following page we can most certainly see Muhammad’s own writing, which is still somewhat clumsy (Fig. 3), but he is surely dedicating himself to the task. At the end of the book, according to scribal etiquette, Muḥammad b. Bakrī gives the date on which the copy was completed: Thursday, the fifth of Jumādā II in the year 1319 AH (19 September 1901 CE).

Niedersächsische Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Göttingen

Our scribe Muḥammad employed centuries-old methods of Middle Eastern manuscript production. The pen he used was a traditional reed pen, cut to shape with a knife. To highlight certain parts of the text (mostly quotes from the original Ājurrūmiyya on which the author of the present work has commented) Muḥammad either used red or violet ink instead of black ink, or he drew little rosette-like elements as text dividers. In the lower margin of verso pages (curiously, only on every second verso page), he added catchwords so that the bookbinder could check that the folia were in the correct order (Fig. 4).

In contrast, other features of Cod. Ms. arab. 552 bear witness to the influence of printing technology in the Middle East and to technological changes of the time. Muhammad’s manuscript was written on an industrially made paper, a wood pulp-based paper which had been available since the early nineteenth century. This cheaper but less durable alternative had gradually driven European watermark paper (made from rags) out of the market. Very probably, the industrially made paper was more easily accessible for Muḥammad or his teachers or relatives. In terms of the layout, Muḥammad used rosette-like elements as text dividers and rounded decorative ‘brackets’ to highlight portions of the text (Fig. 4). Such decorations are often found in printed Arabic and Turkish books of the nineteenth century, either flanking the page numbers in the upper margin or highlighting e.g., Koranic verses in a text. In fact, glyphs for both the rosettes and the ‘brackets’ are still included in most digital Arabic fonts: ﴾۞﴿. The ‘brackets’ have no precedent in Arabic manuscript culture and appear to have been adapted from European typography. Muḥammad b. Bakrī may have seen such glyphs in printed books or even in a printed edition of the very text he was copying.

Apparently, he reproduced other modern layout elements such as centred chapter headings, or horizontal lines to separate portions of text on a page (Fig. 5), and page numbers in the upper outer margins. However, he did not employ any of these features consistently. Some of these elements occur only once or twice while the appearance of others changes every time they occur; it is as if he wanted to try them out and to find various ways of reproducing them by hand. The very fact that the text starts on a single left-hand (recto) side (today fol. 3r, Fig. 1) could also be attributed to the subtle influence of printed books. In earlier times, it was customary for manuscripts to start on the first verso page (right-hand side) of the first opening and to continue on the following recto page (the left-hand side). The first recto page, if it had any text at all, often only carried a small note about the author and the title of the text, presumably added for convenience. In fact, later in life, Muhammad followed this tradition, adding some notes on fol. 2r (Fig. 2) even though the main text did not start on fol. 2v but one page later.

Niedersächsische Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Göttingen

The Göttingen manuscript offers us a window into a fascinating period of change in Middle Eastern book culture. It was written at a time when traditional education was gradually being replaced by modern state schooling, and when handwriting had almost ceased to be the main technique of writing an Arabic book. When making it, at the age of twelve, Muḥammad b. Bakrī consciously or unconsciously mixed traditional ways of manuscript production with more recent elements typically found in printed books. Completing the 294-folia codex must have meant a great deal to him and this might explain why the object was given a durable cardboard binding with an envelope flap typical of Middle Eastern manuscripts. It also explains why he later wrote a comment on the circumstances of its creation. Later in life, at some point in the twentieth century, he probably saw his book as a precious keepsake and an artefact of a bygone era.

Niedersächsische Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Göttingen

Description

Niedersächsische Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Göttingen

Shelfmark: Cod. Ms. arab. 552

Material: paper, 294 leaves

Measurements: 23 × 18 cm

Provenance: Middle East

Date: completed on 5 Jumādā II 1319 ah/19 September 1901 ce

Copyrights

© Niedersächsische Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Göttingen

Reference Note

Cornelius Berthold, A Scribe in Training: The First Manuscript of a Twelve-year-old Student of Arabic In: Leah Mascia, Karin Becker (eds): Artefact of the Month No. 27, CSMC, Hamburg.