What Will Save the Household?

Marco Moriggi

In the heart of Mesopotamia, where the waters of the Tigris and Euphrates skirted the glorious walls of thousand-year-old cities, the fear of illness, of deadly demonic influences, of misfortune and the evil eye, was omnipresent. We find ourselves in the Late Antique period where the favourite means of protection against such evil adversaries was made of ordinary clay and shaped on the potter’s wheel. The vessel under discussion here, IsIAO 5206, can indeed be described as a typical household device: a clay bowl. However, this bowl is different in as much as it is inscribed with ritual spells. But why use a bowl against evil influences? And what do we know about how it was used to protect its owners?

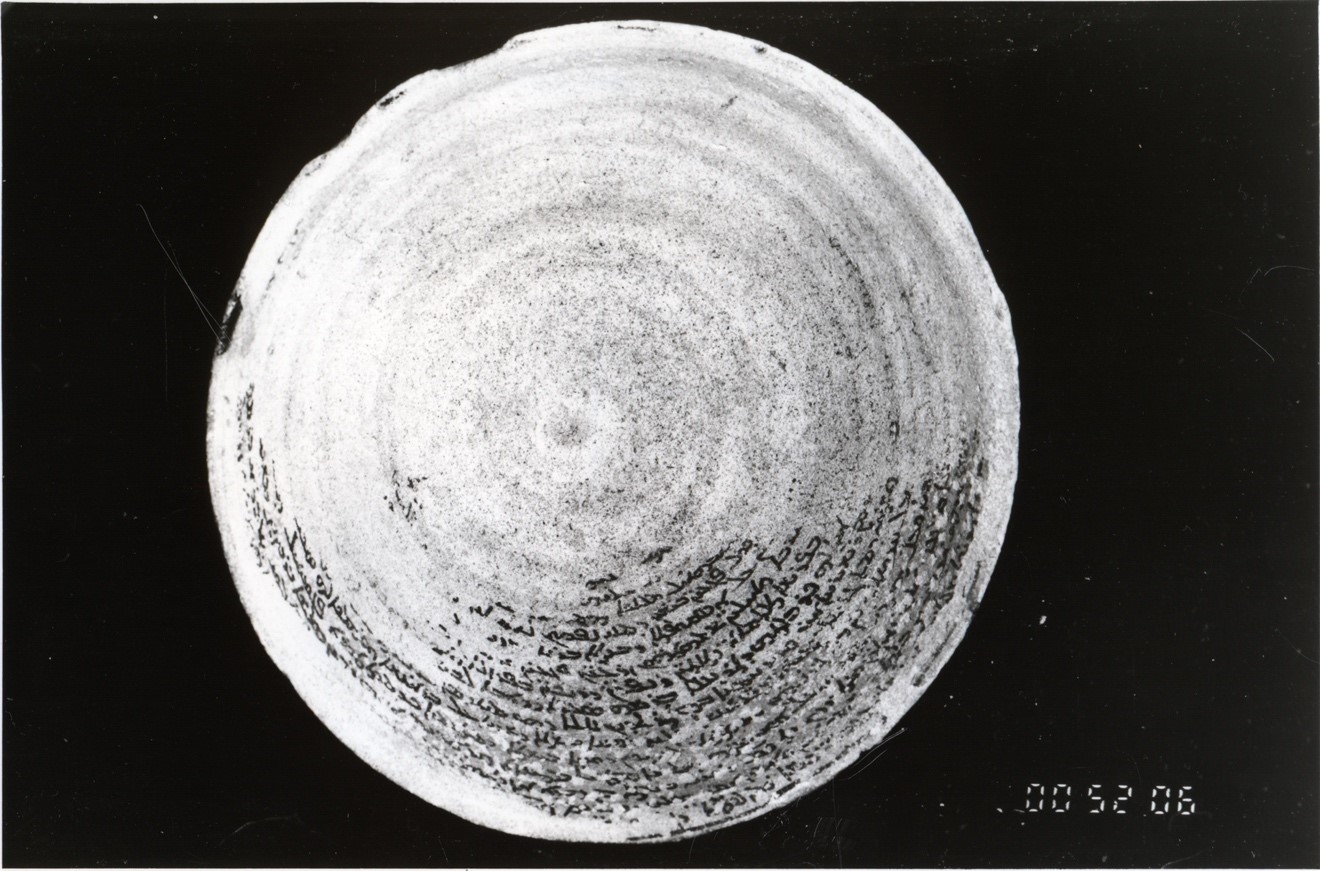

This clay bowl (Fig. 1) was buried sometime between the sixth and the seventh centuries CE, was rediscovered some thirteen centuries later, and found its way into the Museo delle Civiltà in Rome. Our vessel measures 18.2 × 8 cm and thus fits the usual dimensions of this type of object. It is typical of the bowls that were used to eat and drink, to carry or to preserve goods at home, in storerooms, or at the market. However, it was probably never used in such a way.

© Museo delle Civiltà, Roma

Like most bowls, our artefact is a wheel-thrown vessel, but has a ritual function. In such vessels, inscriptions – spells – were written in different patterns. In the present bowl, the spells are written with ink using a reed pen and appear as a spiral on the inner surface of the bowl starting from the lower surface and continuing up to the rim. It is written in Syriac (Aramaic) using the classical Estrangela script, which was typical for this language at the time. Typically, such incantation bowls were written in at least two other varieties of the eastern Mesopotamian area of Late-Antique Aramaic (c. 200– 700 CE): Jewish Babylonian Aramaic (written in Square script) and Mandaic (in the Mandaic script).

The identity of the scribe responsible for writing the text of our bowl is unknown. Scholars generally assume that these kinds of text were written by educated people such as members of religious communities or by high-ranking citizens. These incantations are mostly concerned with defence, for instance, against a demon with specific characteristics, often animal attributes such as ‘the crest of the cock’ and seemingly vampire-like habits, as mentioned in our text. These formulae were intended to protect the client and their family, their possessions, cattle, livestock, and all other items pertaining to their life and health.

These bowls, produced in Mesopotamia in Late Antiquity, often bear witness to pluralism, that is, to the compresence of many traditions. At the time that our bowl was made, Jewish, Christian, Gnostic, and Ancient Mesopotamian influences interacted in the area, and elements of all these various cultures are found in such bowls. On occasion, enemies – their physical appearance and activities – are described in a vivid manner in the protective spells. In our artefact we find phrases such as: ‘[...] he has the crest of the cock on his head, he wears the fur of a wolf [...] she drinks blood, the bones and water of many men’. Unfortunately, the text is very fragmentary, and only about one quarter has survived; thus, it is impossible to deduce the full meaning of the utterances.

Like most of these objects, this ritual vessel has reached a western museum through the antiquities market, and thus we cannot present any well-founded hypothesis regarding its provenance. Nevertheless, some specimens have been properly excavated and — apart from their texts — we are able to assess the original contexts of discovery. For the bowls coming from documented excavations, we know that they were discovered in the territory of present-day Iraq, in an area extending approximately from Aššur in the north to the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in the south. Other bowls were unearthed in Khuzistan, in present-day southwestern Iran. As far as dating is concerned, we may assume that most of the known exemplars, like this incantation bowl, were produced in the sixth and seventh centuries CE, with some specimens possibly produced as early as the fifth century and up until the eight century CE.

The number of bowls brought to light in the last two centuries clearly demonstrates that the practice of inscribing bowls for protection was very widespread. Thus, one may well ask: why use this specific type of object? The first and most obvious answer is that clay is omnipresent in Mesopotamia and had been used as a material to write upon since the earliest days of writing. Clay, therefore, was commonly used to write upon. Despite their commonplace character and their unexceptional appearance, nothing, apart from the inscriptions, distinguished them from the pottery made for use in the home. Thus, our exemplar is a significant and reliable source for the magical Babylonian traditions in Late Antiquity and seems to have been specifically linked to the domestic context.

The archaeological evidence tells us that these bowls are found mainly in kitchens, storerooms, et cetera, where they were buried under the floors, in the corners of the rooms, and under the thresholds. Thus, it is quite probable that our artefact was buried in a domestic environment, for example in a room in a house which, in this way, was to be protected from evil influences. As with many other incantation bowls – with their texts and the durability of the baked clay on which they were written – this vessel was probably perceived as a permanent protective device in the household.

Material traces of the kinds of ritual practised with such bowls have not yet been discovered; however, future research may help us, firstly, to ascertain the practices which made this object – and other ritual vessels – effective as protection against demons and pests and, secondly, to further investigate the materiality of the bowls.

References

- Frankfurter, David (2015), ‘Scorpion/Demon: On the Origin of the Mesopotamian Apotropaic Bowl’, Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 74: 1–10.

- Montgomery, James A. (1913), Aramaic Incantation Texts from Nippur, Philadelphia: The University Museum.

- Moriggi, Marco (2014), A Corpus of Syriac Incantation Bowls. Syriac Magical Texts from Late-Antique Mesopotamia, Leiden/Boston: Brill.

- Shaked, Shaul, James N. Ford, Siam Bhayro (2013), Aramaic Bowl Spells. Jewish Babylonian Aramaic Bowls Volume One, Leiden/Boston: Brill.

- Venco Ricciardi, Roberta (1973–1974), ‘Trial Trench at Tell Baruda (Choche)’, Mesopotamia, 8–9: 15–20.

Description

Location: Museo delle Civiltà, Roma

Shelfmark: IsIAO 5206

Material: Clay

Dimensions: 18.2 x 8 cm

Copyrights

(© Museo delle Civiltà, Roma)

Reference Note

Marco Moriggi, What will Save the Household? In: Leah Mascia, Karin Becker (eds): Artefact of the Month No. 26, CSMC, Hamburg.