A ‘Priceless Mexican Book Written in Hieroglyphs’

Nikolai Grube

In the year 1734, the court chaplain Johann Christian Götze, who was the librarian at the Electoral Library in Dresden, was sent to Vienna and Rome in order to procure a number of precious books and manuscripts for the Elector of Saxony. One of the hundreds of manuscripts and books he brought back to Dresden was a ‘priceless Mexican book written in hieroglyphs’. Götze’s own estimation of his acquisition is expressed as follows: ‘Our Royal Library secured the privilege of possessing such a rare treasure, ahead of many others.’ He was evidently very aware that the document he had acquired for his library – a document which originated in the pre-Hispanic manuscript culture – was extremely valuable.

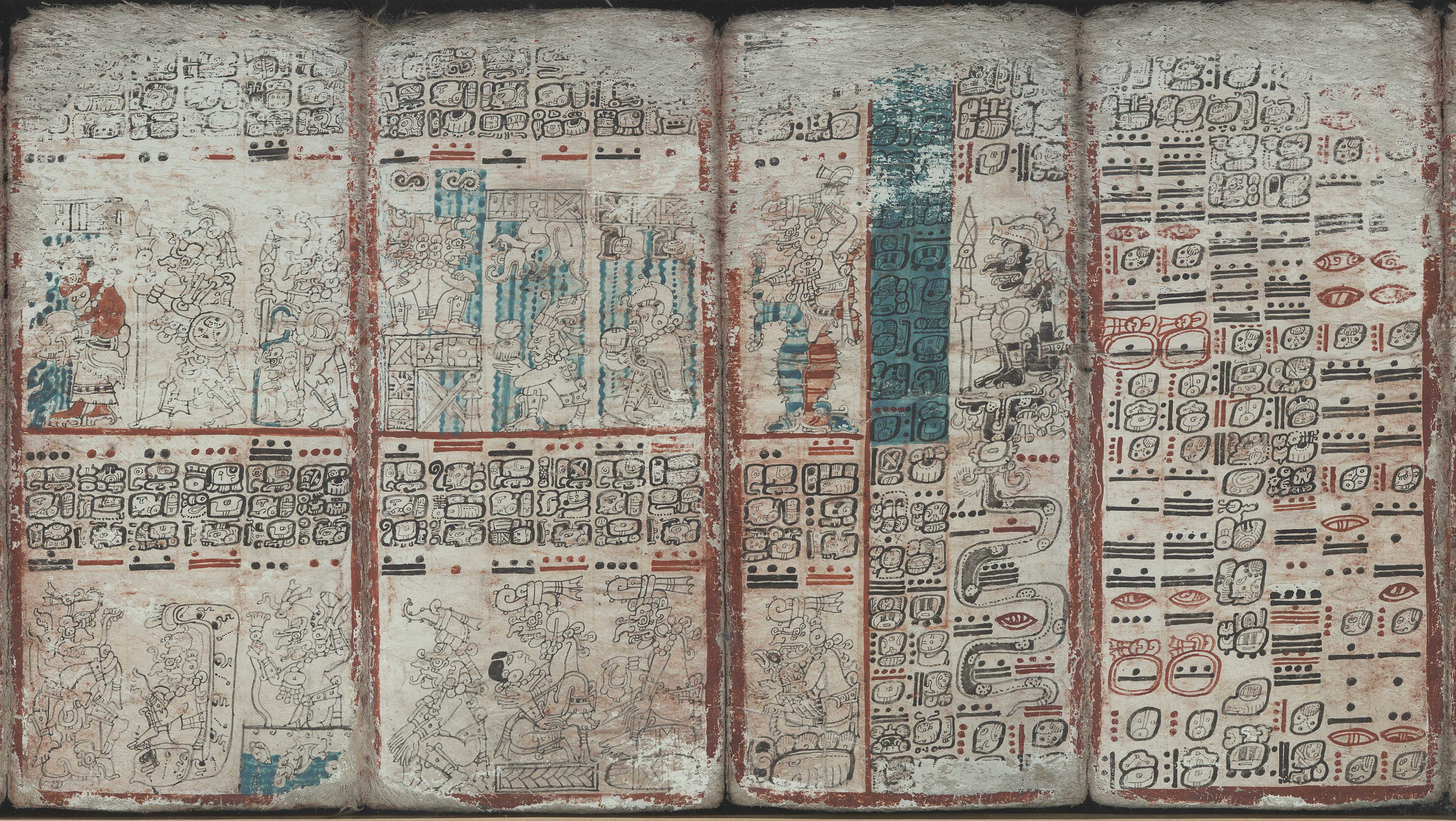

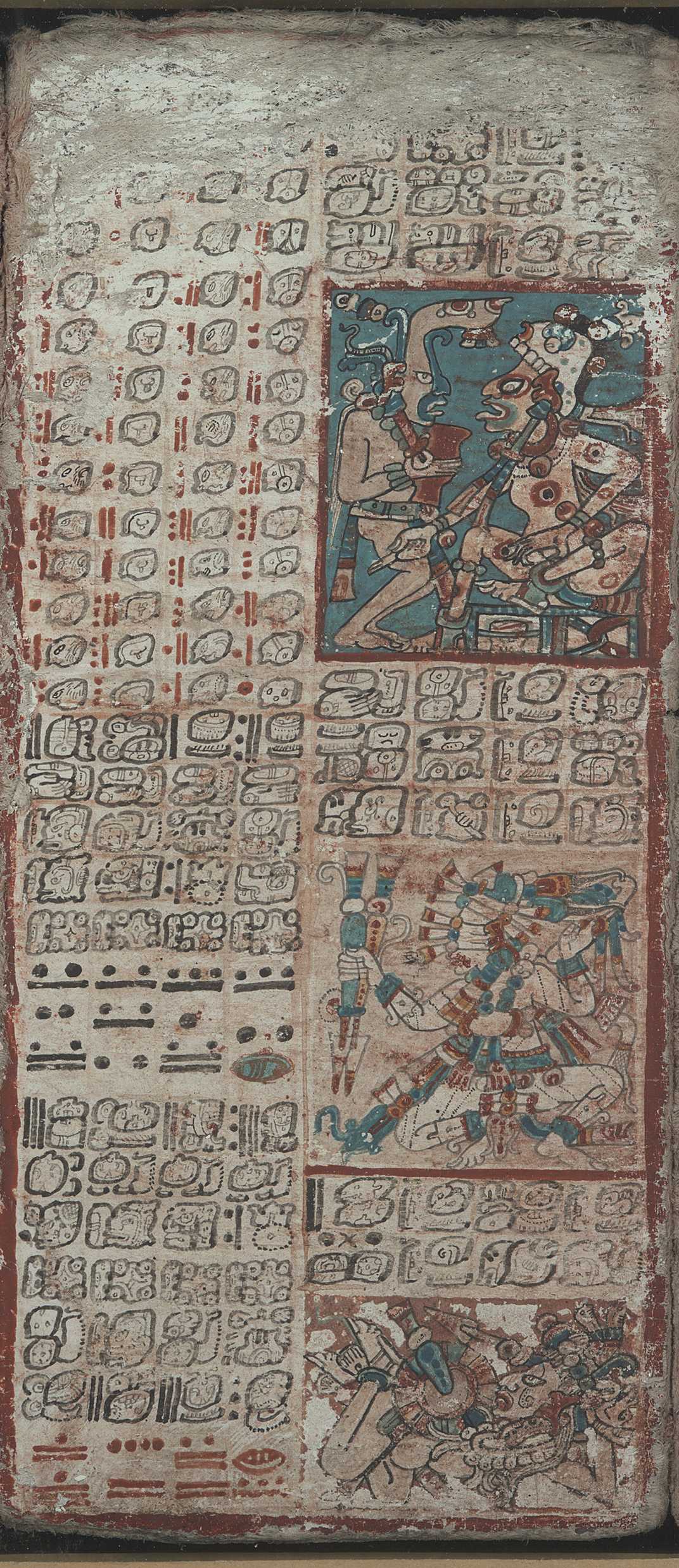

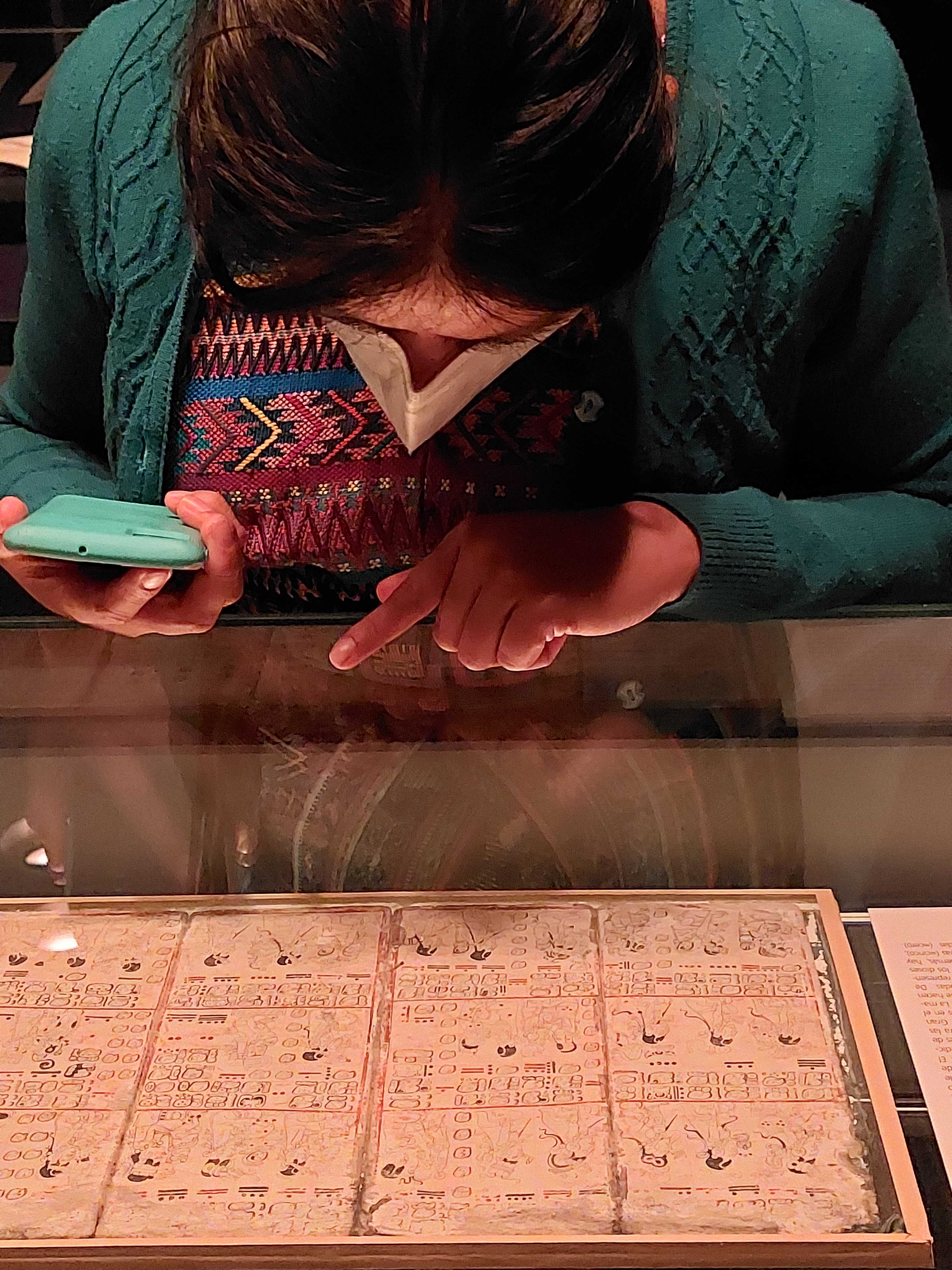

The so-called Dresden Maya-Codex is the most important manuscript of the pre-Hispanic Maya culture and one of only four Maya manuscripts to have survived the tropical climate and the burning of books undertaken by Spanish priests. It consists of two strips of paper made from the bark of a fig, both sides of which have a coat of gypsum (calcium sulphate) which can be written on. However, in contrast to the Codex format the bark paper strips were not cut into separate pages, rather, they were folded into 39 folios in Leporello (fanfold) format, thus, approximately 91 mm in width and 205 mm in height, a format which the Dresden Codex shares with other Maya manuscripts. When spread out, the Codex has a length of 3.56 meters.

The Maya word for manuscript, hu’un, has the same meaning as the word for fig trees (Ficus spp) or mulberry trees (Morus spp) from which both writing materials and paper were obtained. For the production of hu’un-paper freshly cut branches were freed of the outer bark and the milk was scraped off. The inner bark was then either softened in running water or cooked in lime water. The wet fibres were then placed in three layers, more or less at right angles to each other, on an elongated drying board and felted by tamping with a grooved bark beater. The next step in the production of the manuscript was to cut the felted sheets of paper to the intended dimensions of the finished manuscript, which was almost certainly done with a razor-sharp obsidian blade. The paper strip was then folded into the Leporello format. The last step in preparing the codex for the final painting was to apply a smooth white layer directly onto the bark paper of each side of the page. This layer consisted of calcium carbonate or calcium sulfate (gypsum) heated at 150 degrees and ground into a powder. The powder was mixed with water and quickly applied to the pages to create a smooth white writing surface on which errors could be easily corrected by scraping off the white layer and reapplying the mixture. Presumably, this layer of plaster was also the reason why the paper strip was folded and not rolled: because it made the paper stiff and could easily detach itself.

The Dresden Codex, like other Maya books, probably had a binding made of wood which – we may assume – was, in many cases, covered with jaguar skin. This assumption originates primarily from painted pottery of the Late Classic period (600–900 AD) on which scribes are frequently shown at work, painting with their fine brushes in books that – without exception – have a jaguar-skin binding. The hieroglyphic sign for ‘book’, hu'un, also shows a stylized codex between two covers made of jaguar skin. The books were stored in boxes made of wood or stone, a few of which are still preserved today.

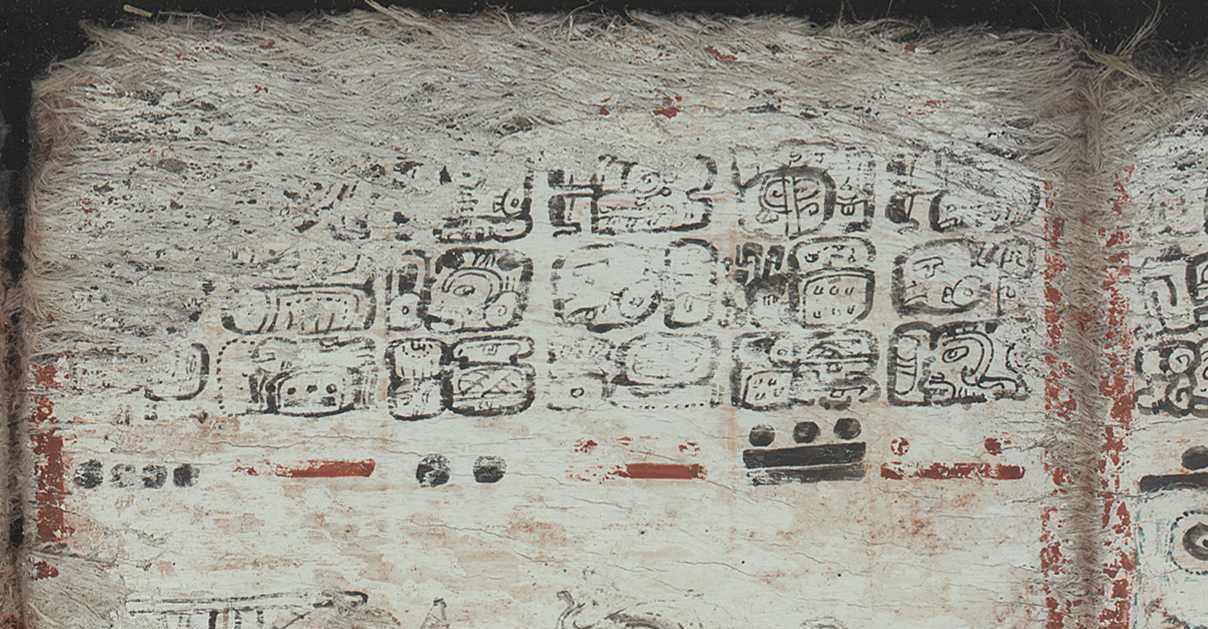

The signs were applied with fine brushes of various textures in black, and sometimes also in a red colour. The black colour was obtained from soot, the pigments for the red colour were gained from hematite. The writing of the codices was in the hands of highly respected scribes. The different styles of writing and painting in the Dresden Codex clearly indicate that more than one scribe was at work here; the codex was created in a workshop or atelier where at least eight different scribes worked under the supervision of an experienced master scribe. Some pages were worked on by two scribes, while other scribes, such as the master scribe, wrote several chapters in succession. Evidently, the Dresden Codex was never completely finished, because some of the prepared pages remained completely blank, and on other pages the scribes only painted the outlines of hieroglyphs without completing the fine lines within.

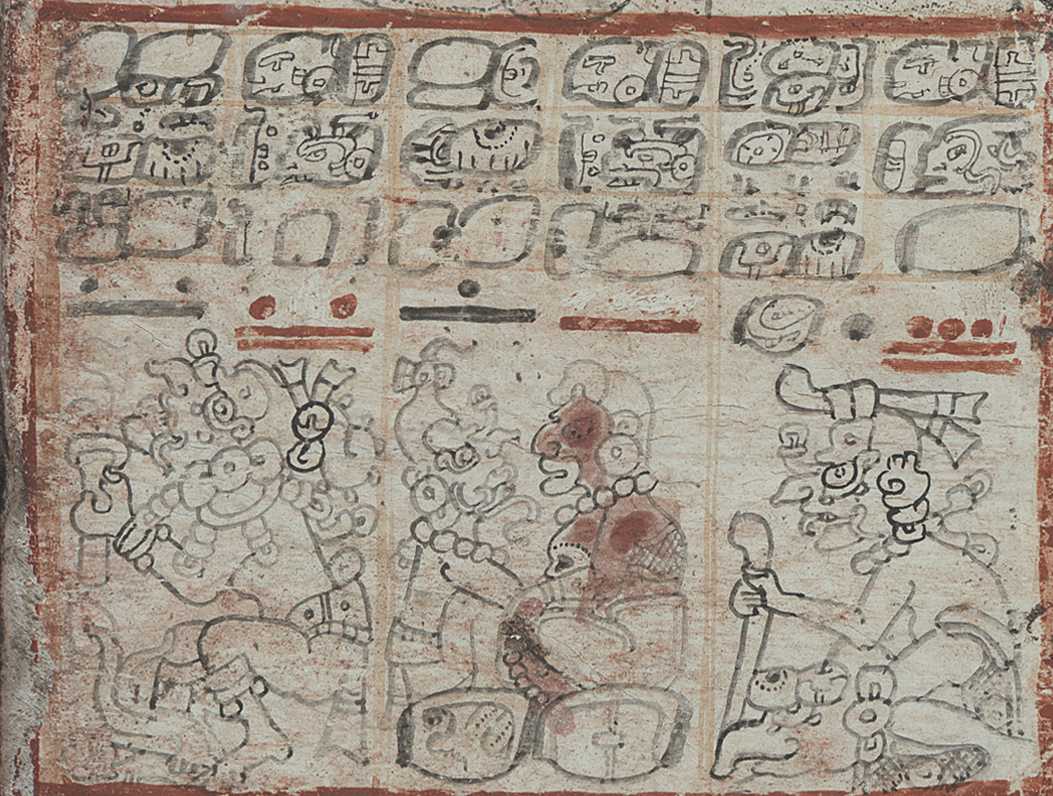

The Maya script is logosyllabic, i.e. there were both syllabic signs (syllabograms, always in the order consonant-vowel) and word signs (logograms) that could be freely connected with each other. The signs, especially the logograms, kept their iconic character for over 2000 years and represent what was to be communicated in conventionalized pictorial signs. With the help of the syllabograms, it was possible to faithfully reproduce Classic Mayan, the written language that had been extensively used for hundreds of years. In addition to the texts – and illustrating the texts – are numerous intriguing pictures. Almost without exception, they show gods named in the accompanying texts, as well as the fate to which they subject people on certain calendar days.

The Dresden Codex consists of a number of chapters devoted mainly to religious, astronomical and calendrical topics. The almanacs and prophetic texts of the codex, as well as the astronomical tablets, are therefore related to calendrical indications, which can be quickly recognized by the numerical signs – black or red bars for a ‘five’, dots for ‘ones’, and a stylized shell for ‘zero’. Individual chapters may extend over several pages. Each page is divided into three or four vertical sections, separated by red lines. For example, a chapter might be written in only one of the sections, but extend across several pages. The reader could then open the pages he needed in order to survey the entire chapter. However, there are also pages that are not divided into sections, thus, the arrangement of the pages ultimately depended on the subject that was being treated. The somewhat delicate pages of the books were probably not allowed to be touched with the fingers; thus, to trace the hieroglyphic columns, ‘index fingers’ carved from wood or bone were used, similar to the yad used for reading the Torah.

Like the Dresden codex, the other three surviving Maya codices deal with religious-calendrical and astronomical topics. But this is only a coincidence. Spanish documents from the early colonial period report a wide variety of subjects recorded in the books, from historical chronicles to tribute lists and even literary works. We now believe that there were libraries in the royal palaces, maintained by scribes and librarians, and that books may also have been in the possession of priests; indeed, the Dresden Codex seems to have been a manual used by a priest. Unfortunately, it is not known how the books were read or recited, although Spanish priests and chroniclers were able to observe their active use. However, due to their lack of interest in indigenous culture, their descriptions are very brief. Moreover, the books were considered to be records of the old, pagan faith, so that the clergy collected all the books they possibly could and consigned them to the flames at public auto-da-fés. The most famous book burning was held on July 14, 1562, at the instigation of the Franciscan friar Diego de Landa, in front of the Mani monastery in Yucatán: ‘We found among them a great number of books with these letters, and because they contained nothing that was free of superstition or the wiles of the devil, we burned them all, which the Indians deeply regretted and lamented’, writes friar de Landa rather laconically.

We do not know how the Dresden Codex survived the book burnings and reached Europe. There are strong indications that it was given by the Maya as a gift to their guests, i.e. to the first Franciscans who worked in Campeche between 1536 and 1539 under the leadership of Fray Jacobo de Testera. It is possible that Jacobo de Testera took the Dresden Codex across the Atlantic later and presented it to Emperor Charles V in Ghent. The manuscript then seems to have made its way from the Spanish Netherlands through Germany and perhaps even Italy to Austria, where it most likely became a prestigious gift given by a member of the court of Charles V to a member of the Austrian Habsburg court in Vienna. There, it was finally acquired by the Dresden court chaplain Götze in 1734. The fact that the codex must have reached Europe through a Spaniard was already suspected by Götze: ‘It was found a few years ago in the possession of a private person in Vienna, and, as an otherwise unknown item, it was easily obtained at no cost. Without a doubt, it is from the estate of a Spaniard who either himself – or his ancestors – had been in America’.

Today, the Dresden Codex is one of the most precious objects in the Library of the State of Saxony and the University of Dresden where it can be seen in the treasury of the Book Museum. It is the only Maya codex accessible to visitors, and Maya people from Guatemala and Mexico frequently make the long journey to Dresden to see the codex, for it documents the existence of the millennia-old book and writing culture of their ancestors.

Digitised Manuscript

https://digital.slub-dresden.de/werkansicht/dlf/2967/1

References

- Anders, Ferdinand and Helmut Deckert (1968), Codex Dresden, Graz: Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt.

- Bricker, Victoria R. and Harvey M. Bricker (2011), Astronomy in the Maya Codices, Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society.

- Chuchiak IV, John F. (2012), ‘Contextualizing the Origins of the Dresden Codex: Colonial Encounters with Maya Hieroglyphic Books and the Most Plausible Provenience of the Maya Dresden Codex’, in Nikolai Grube (ed.), Maya Literacy in the Postclassic Period: New Research on the Dresden Codex (in press).

- Förstemann, Ernst (ed.) (1880), Die Mayahandschrift der Königlich öffentlichen Bibliothek zu Dresden, 74 Tafeln in Chromo-Lichtdruck, Leipzig.

- Förstemann, Ernst (1901), Commentar zur Mayahandschrift der Königlichen öffentlichen Bibliothek zu Dresden, Dresden: Verlag von Richard Bertling.

- Grube, Nikolai (2012), Der Dresdner Maya-Kalender. Die vollständige Handschrift, Freiburg: Herder Verlag.

- Hagen, Victor Wolfgang von (1944), The Aztec and Maya Papermakers, New York: J.J. Augustin.

- Schwede, Rudolf (1912), Über das Papier der Maya-Codices u. einiger altmexikanischer Bilderhandschriften, Dresden: Verlag von Richard Bertling.

- Thompson, John Eric S. (1972), A commentary on the Dresden Codex, a hieroglyphic book. American Philosophical Society, Memoirs 93, Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society.

- Zimmermann, Günter (1956), Die Hieroglyphen der Maya-Handschriften, Universität Hamburg, Abhandlungen aus dem Gebiet der Auslandskunde, Band LXVII, Reihe B (Völkerkunde, Kulturgeschichte und Sprachen, Band 34), Hamburg: Cram, de Gruyter.

Description

Schatzkammer of the Buchmuseum, Sächsische Landes- und Universitätsbibliothek, Dresden

Shelfmark: Mscr.Dresd.R.310

Material: Paper from the bark of the fig tree coated with a fine layer of gypsum

Dimensions: Total length 356 cm (in two parts of 9 cm × 182,5 cm and 9 cm × 174,3 cm), originally folded in the Leporello style

Provenance: fourteenth or fifteenth century, post-classical Maya culture, probably from the Yucatan peninsula

Reference Note

Nikolai Grube, A ‘priceless Mexican book written in hieroglyphs’ In: Wiebke Beyer, Karin Becker (eds): Artefact of the Month No 23, CSMC, Hamburg, https://www.csmc.uni-hamburg.de/publications/aom/023-en.html