A Journey through Kingdoms

A letter from Tušratta to Amenhotep III

Leah Mascia and Szilvia Sövegjártó

The idea that letters can travel great distances is as true today as it was in antiquity. Indeed, the correspondence between sovereigns knew almost no limits. In the fourteenth century BCE the rulers of the ancient Near East communicated with each other in Akkadian, the lingua franca of the time, written on clay tablets in cuneiform writing. The present document – EA 23 (BM 29793) – offers an interesting insight into the diplomatic exchange between two rulers, announcing the journey of a divine statue from the mountain region of Northern Mesopotamia to the capital city of Thebes in Upper Egypt. Strangely, however, the clay tablet was found at the ancient site of Tell el-Amarna, hundreds of kilometres to the north. Why was the letter discovered so far away from its original destination?

© The Trustees of the British Museum

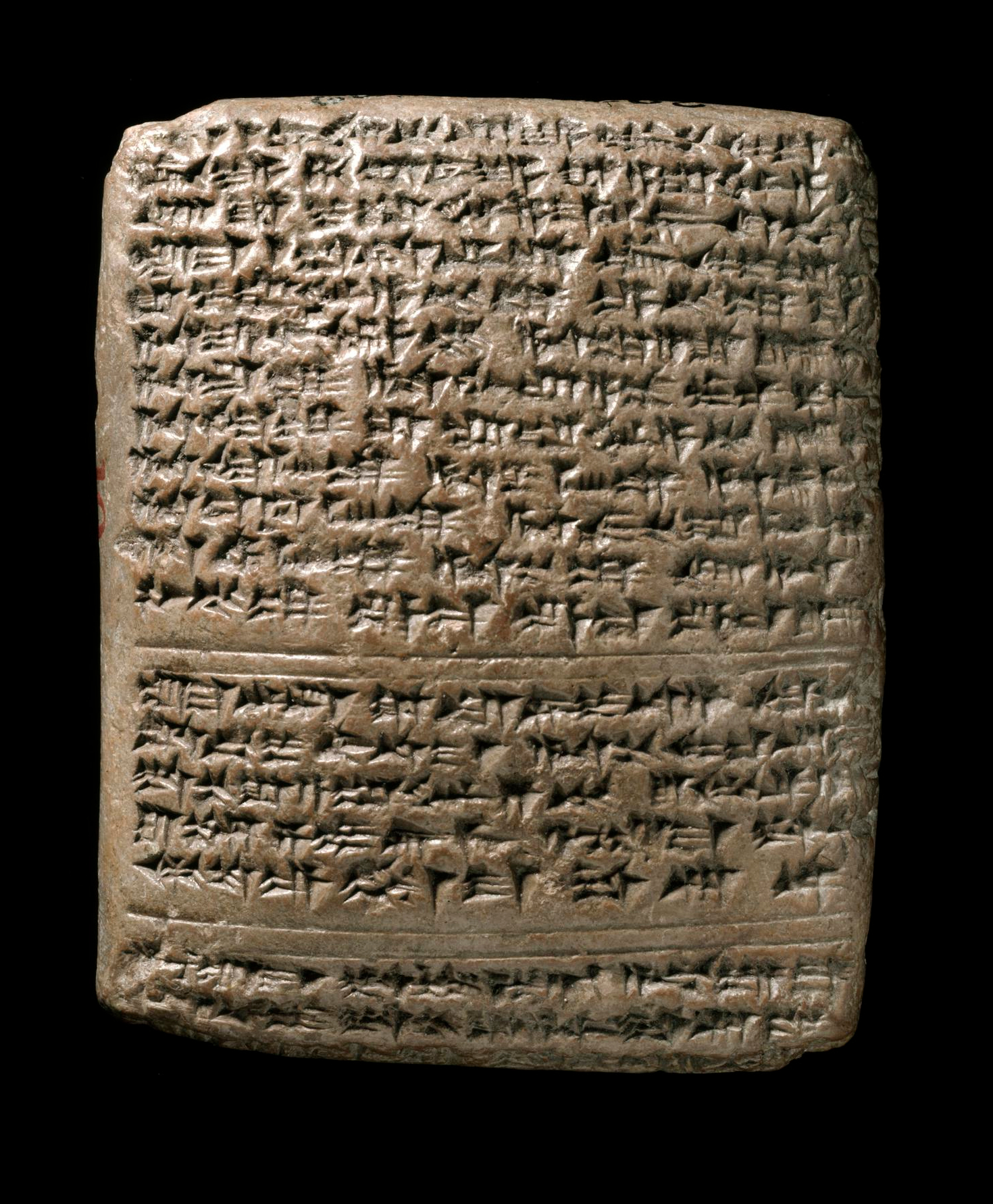

EA 23 (BM 29793) is a letter sent by Tušratta, king of Mitanni (c. 1370–1350 BCE), a kingdom in northern Syria in the 15–13th century BCE, to Amenhotep III (c. 1390–1353 BCE), the ninth ruler of the Eighteenth Egyptian Dynasty. Now part of the collection of the British Museum, this manuscript was written on a clay tablet with a reed stylus in cuneiform script. Such tablets were once commonly found in the ancient Near East and had some advantageous properties compared to other materials like papyrus or parchment: after the tablet was dried, the text – in our case, the diplomatic message – could not be altered without leaving distinct traces.

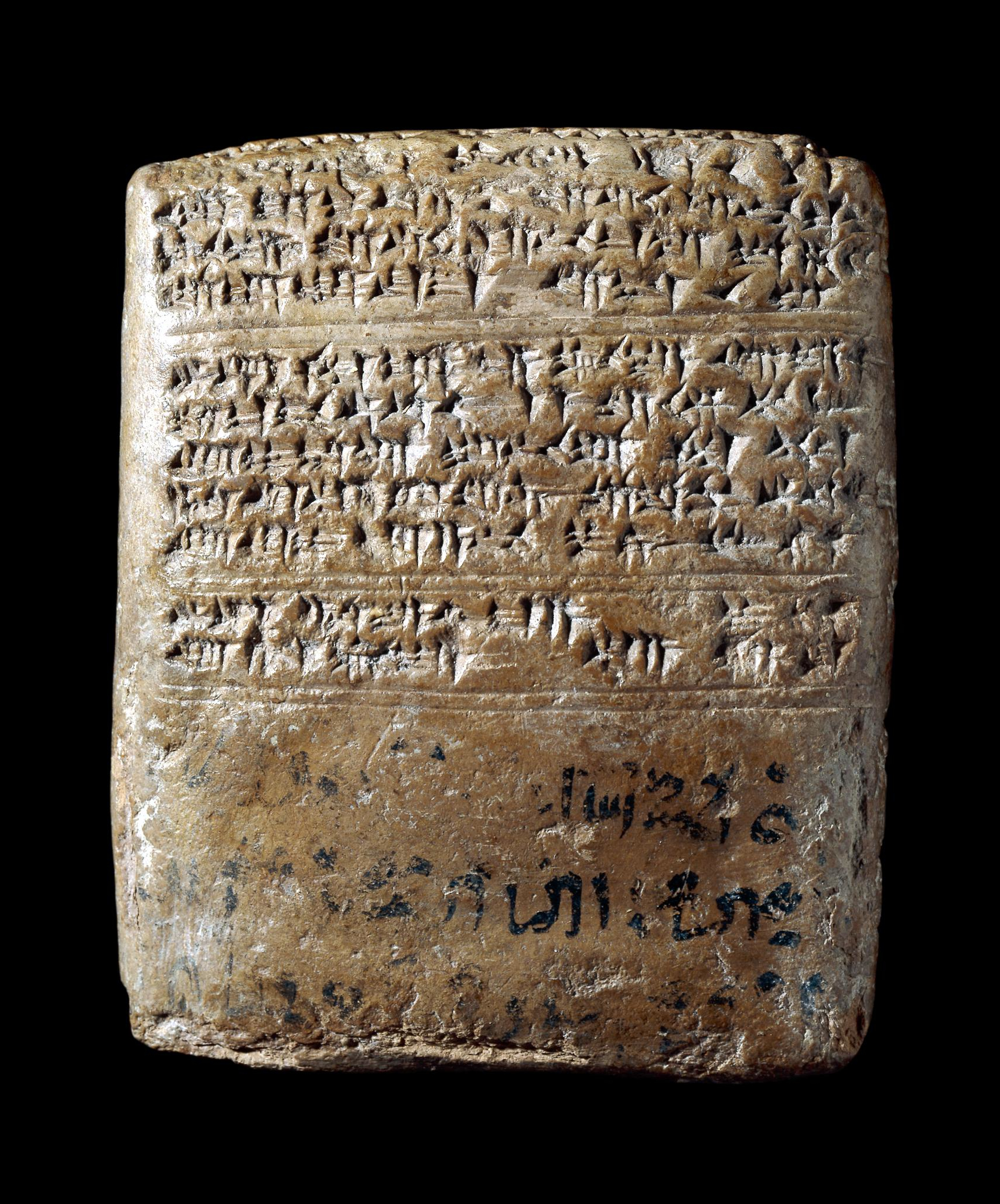

Our cuneiform manuscript contains 32 lines of text divided into five paragraphs, separated by double rulings. The text is inscribed in the Middle Babylonian ductus of the Akkadian language, followed by a brief note written in the Egyptian hieratic script in black ink. The letter belongs to a corpus of clay tablets known as the ‘Amarna Letters’ unearthed in the modern village of Tell el-Amarna. This settlement was built on the ruins of ancient Akhetaten (‘The Horizon of the Sun-Disc’), the capital city founded in Upper Egypt by Amenhotep IV, also known as Akhenaten (c. 1353–1336 BCE), son and successor of Amenhotep III, who was the addressee of our manuscript. Thirteen letters (EA 17–29) sent by Tušratta were found in the Tell el-Amarna archives, nine written to Amenhotep III, one to the mother queen Tiy, and three to Akhenaten.

Rulers sent not only letters to each other but also exchanged gifts. The letter EA 23 reports the impending visit of the goddess Šauška of Nineveh to the Egyptian court. Šauška was a goddess in the Hurrian pantheon venerated in Mitanni. The goddess who visited Egypt was in fact a statue and her visit a political act. Sending such a divine statue was regarded as a sign of great esteem, as these statues were considered manifestations of the gods themselves. In the letter, the king lets the goddess speak herself:

The reason for such an important deity, the highest goddess of the Mitanni pantheon under the reign of Tušratta, to pay a visit to the faraway court of Egypt is debated. It may have been related to the fact that the Mitanni princess Tadu-Ḫeba, the daughter of Tušratta, was married to Amenhotep III, and is also mentioned in the letter’s greeting formula:

As the practice documented in EA23 testifies, good relations were cultivated through reciprocal actions, mainly gifts and other courtesies. But the language of the letter – the established phraseology it uses – points to the close relations between the two rulers:

© The Trustees of the British Museum

The letter was dispatched with a group of royal messengers whose identity is unknown. Normally, they travelled by caravan, bearing gifts and other goods destined for other royal courts. These journeys were dangerous and, while following the mercantile routes, took weeks or even months. The caravan bringing the message of King Tušratta to the Egyptian pharaoh Amenhotep III would have traversed the mountain landscape of the kingdom of Mitanni, crossed the lands of the realm of Canaan, and sailed up the Nile, finally reaching the city of Thebes (modern Luxor) after a journey of around 1800 kilometres.

Upon arrival of the letter at the Egyptian court, the administrative personnel of Amenhotep III added a brief three-line note written in hieratic on the tablet. The so-called hieratic docket was a technical note written by the scribes of the ‘Records Office’ (i.e. the royal archives) recording the date of arrival of the message and the identity of the person or persons who delivered it. The annotation not only testifies to an administrative procedure well known in the Pharaonic tradition; it provides further insights into the perilous journey of this clay tablet from the kingdom of Mitanni to the court of pharaoh Amenhotep III, and later to the archives of Tell el-Amarna.

The docket begins with a standard formula attesting that the letter had arrived in the thirty-sixth year of the reign of Amenhotep III when the king was ‘in the southern villa of the house of rejoicing’, most likely referring to the pr ḥʽy namely the palace city of Malkata. Amenhotep III built this royal residence in western Thebes during the latter years of his reign. In this sense, the reference seems to explicitly identify the place where the document was originally received and presumably stored in the remaining years of the king’s reign. Not the entire docket has been preserved; it is possible that the names of the Mitanni messengers were also recorded on the tablet, as is the case with most ‘Amarna letters’ with similar notes.

Apparently, however, the tablet did not stay in Thebes. Given that it came from an antiquarian market, the exact place where it was found is not known. It seems likely, however, that it was brought to the city of Akhetaten, 400 kilometres from its original destination, together with the other ‘Amarna Letters’. Akhetaten was the newly built capital city to which Amenhotep III’s son and successor Akhenaten transferred his court in the sixth year of his reign.

If the letter sent to Amenhotep III and delivered to the royal palace of Malkata at Thebes, why was it discovered so far away in the new capital built after his death? Presumably, there were good reasons for preserving part of the so-called ‘Mitanni correspondence’ of the deceased pharaoh, and moving it to the administrative archives of Akhetaten. It is possible that the Mitanni princess, Tadu-Ḫeba, married Akhenaten, though this has not yet been verified. Certainly, the Tušratta and the new pharaoh continued to have fraternal relations. The fact that these letters were kept is a sign of the good diplomatic relations between the two kingdoms.

Following condemnation of Akhenaten’s religious reforms, Tell el-Amarna was abandoned shortly after his death. This may explain why the administrative documents, including EA 23 and the rest of the correspondence dating to the reign of Amenhotep III, were left behind and remained unknown for thousands of years.

Thus, the little clay object – no bigger than the palm of one’s hand – waited until the late nineteenth century CE before it went on a further expedition of thousands of kilometres. In the 1880s, the letter was acquired, probably in Cairo, by Sir Ernest A. T. Wallis Budge as part of a corpus of some eighty Amarna tablets. On this occasion, the document travelled from the Egyptian deserts, going up the Nile and crossing the Mediterranean Sea, to the British Museum in London. We might wonder whether this was the last voyage in the unexpectedly adventurous life of this clay tablet or perhaps simply one of the many chapters in a long story to come.

Digitised manuscript

EA 23 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/W_1888-1013-78 (accessed on 1 July 2022)

References

-

Lynn Holmes, Yulssus (1975), ‘The Messengers of the Amarna Letters’, Journal of the American Oriental Society, 95/3, 376–381.

-

Mynářová, Jana (2007), Language of Amarna – Language of Diplomacy: Perspectives on the Amarna Letters, Prague: Czech Institute of Egyptology.

-

Petrie, William M. Flinders (1894), Tell el Amarna, London: Methuen & Co.

-

Pfoh, Emanuel (2016), Syria-Palestine in the Late Bronze Age: An Anthropology of Politics and Power, London-New York: Routledge.

-

Rainey, Anson F. (ed.) (2015), The El-Amarna Correspondence: A New Edition of the Cuneiform Letters from the Site of El-Amarna based on Collations of all Extant Tablets, Leiden-Boston: Brill.

- Singer, Graciela Gestoso (2016), ‘Shaushka, the Traveling Goddess’, Trabajos de Egiptologia, 7: 43–58.

Description

Location: British Museum, London

Shelfmark: EA 23

Material: Clay

Size: c. 6,8 × 8,5 cm

Origin: Tell el-Amarna

Copyright Notice

Copyright of illustrations and photographs:

© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

Reference Note

Leah Mascia and Szilvia Sövegjártó, A Journey through Kingdoms: A letter from Tušratta to Amenhotep III In: Wiebke Beyer, Karin Becker (eds): Artefact of the Month No 22, CSMC, Hamburg, https://www.csmc.uni-hamburg.de/publications/aom/022-en.html