'Just as Christ stood pacified in the olive garden, all weapons shall be pacified.'

How Marie Geffers made her son-in-law invulnerable

Theresa Müller

At the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914, Marie Geffers, a farmer’s wife from Süpplingenburg in present-day Lower Saxony, wrote a letter for her son-in-law, Richard Schulze. This letter was certainly not a normal letter. The hand-written text was meant to give her daughter’s husband magical protection against any of the dangers which might confront him as a soldier. What kind of mysterious text was this? What kind of role did the act of writing play here? And what did Christ have to do with all this?

© State Museum in Braunschweig, A. Pröhle

Marie Geffers’ letter belongs to a special category of paper amulets known as ‘Letter from Heaven’ or ‘Letter of Protection (for the house)’ which were written and handed down in private households well into the twentieth century. Although the content of the present letter includes various Christian topoi – for example, teachings on the Trinity or the Ten Commandments – it was never legitimised by the church. The present example is composed of various text elements which are typical for a Letter from Heaven. However, the sequence and specification of these elements are unique for each case. The reason is that such letters were regularly copied and handed on in private circles. Marie Geffers would probably have copied her version from one or more templates circulating among her friends and neighbours, letters which had proven effective in the past. Such hand-to-hand distribution constantly led to new variants of these letters, for not only mistakes were copied, but also diverse templates – both oral and written – were merged into new varieties.

The numerous wars in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries meant that the practise of writing heavenly letters, of which the one under discussion is an example, became ever more widespread. Marie Geffers wrote the amulet – as did others – because she was concerned about the life of her son-in-law and about the possible consequences of the war for her family. Like many other women she gave a member of her family an object to take into the field – something which she believed to have supernatural power to protect. For the text of the Letter from Heaven contained detailed passages intended to protect against firearms – pistols and cannon – as well as against other weapons such as swords and daggers.

© State Museum in Braunschweig, A. Pröhle

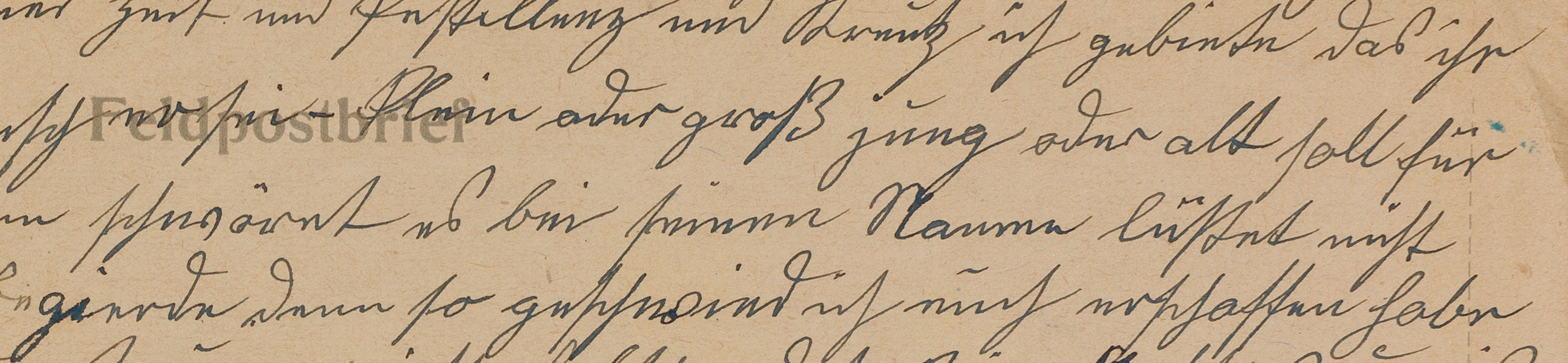

Marie Geffers wrote the Letter from Heaven by hand in Kurrentschrift (‘German cursive’) using ink. The printed sheet on which she wrote was mass-produced at the time, specifically made for writing to the front or for the soldiers to write home. The sheet – 30.5 cm in width and 21.5 cm in length – has a specific form: the first fold allows the sheet to be folded into four sides or pages; printed in the upper half of the first page is the word ‘Feldpostbrief’ (‘letter to the front’) as well as three printed lines for the address of the recipient (Fig. 2). Three further printed lines on the lower half of the same page are marked with the word ‘Absender’ (‘sender’). When opened, the sheet offers one double-paged side as well as one half of the reverse side to write the letter. A further fold allows the letter to be closed so that its content remains unseen and only the names and addresses of the recipient and the sender are visible.

Marie Geffers, however, paid no attention to the printed layout; instead, she used the whole surface as if it were blank. She even wrote over the printed text so that it is barely readable. The frayed folds of the paper – slightly torn in places – indicate that the Letter from Heaven was folded twice and that its owner kept it like this. The writing suggests that Marie Geffers was either not proficient in handwriting or wrote in great haste, perhaps in order to finish the amulet just before her son-in-law left. The writing is clumsy and often irregular. The upper and lower curves of the cursive writing intersect from one line of writing to the next, and there are many inkblots. The individual words are very close together and sometimes overlap each other so that it is difficult to distinguish between the beginning and end of a word (Fig. 3).

© State Museum in Braunschweig, A. Pröhle

The text contains many grammatical mistakes and even words and sentences that make no sense. And while there is almost no punctuation, many words and phrases are repeated – a result of the process of copying through which words ‘slipped’ into a line where they did not belong:

It is no longer possible to know whether some of the mistakes were made by Marie Geffers herself or whether she simply copied them. Like many others that have survived, this Letter from Heaven shows us that, at the beginning of the twentieth century, proficiency in reading and writing could not be taken for granted among the general public; indeed, the writing of such a text may have involved a great amount of physical and mental effort.

This short extract also shows whose protection Richard Schulze was to receive through the Letter from Heaven: God’s. However, this protection was dependent on certain conditions: there were practical rules of behaviour such as observing the ten commandments, wearing the amulet directly on the body at all times, and the instruction to continually copy the letter and pass it on to others. Furthermore, there were clear rules concerning one’s attitude or feelings towards the amulet which were a prerequisite for the protection it offered: the efficacy of the heavenly letter was never to be doubted. The belief of those who wrote the letter and those who wore it should be unshakeable – that the amulet was God’s word and God’s directive. If Marie Geffers or Richard Schulze should break these rules, the letter threatened terrible punishment. The two poles – deliverance and damnation – could have particularly ominous consequences, given the claim that the letter had been written by God or Christ himself. The constant use of the first person singular, ‘I’ in the text, highlights the fact that, with this letter, God or the Holy Trinity (‘In the name of the Father x of the Son x and of the Holy Ghost’) was directly contacting the individuals concerned. Thus, the promise of protection, on the one hand, and the threat of death and damnation, on the other, imply the highest possible authority – divine authority – to guarantee the success of the amulet:

[…] und wer dieses nicht glaubet der soll des Todes sterben bekehrt ihr euch nicht von euren Sünden so wird all ihr ewig bestraft ich werde euch richten wenn ihr mir an Jüngstengericht Antwort gebt von andere Sünden wer diesen Brief bei sich hat den wird kein Donnerwetter treffen halte meine Gebote welche ich durch meinen Engel Michael gesand habe.

[…] and whoever does not believe this should die the death if you do not repent for your sins so you will all be punished eternally I will judge you when you give me answer at the Last Judgement from other sins whoever has this letter on him will not be struck by thunder keep my commandments that I sent through my angel Michael.

The above quote articulates the precondition for the effectiveness of the Letter from Heaven, that is, the absolute belief in the magical nature of the text. A further condition is conveyed in the following:

[…] ich sage mich das Jesus Christus diesen Brief geschrieben hat und wer ihn nicht offenbart der ist verflucht der Christbohm Kirche dieser Brief sollen wir uns unter einander abschreiben […]

[…] I tell myself that Jesus Christ wrote this letter and whoever does not proclaim it is cursed of the Christbohm church this letter we should copy from each other […]

Thus, to create an effective amulet Marie Geffers had to copy the Letter from Heaven for another person and to circulate both her own text and her knowledge about the letter. Importantly, the attitude towards the text, and the way in which it was handled could either sustain its efficacy or destroy it. Furthermore, if despite the amulet, Richard Schulze had been wounded or even killed this would not be considered as proof of its inefficacy, rather, it would mean that the persons involved had not observed the appropriate rules. Thus, those involved were themselves responsible for sustaining or impairing the protection offered by the Letter from Heaven.

© State Museum in Braunschweig, A. Pröhle

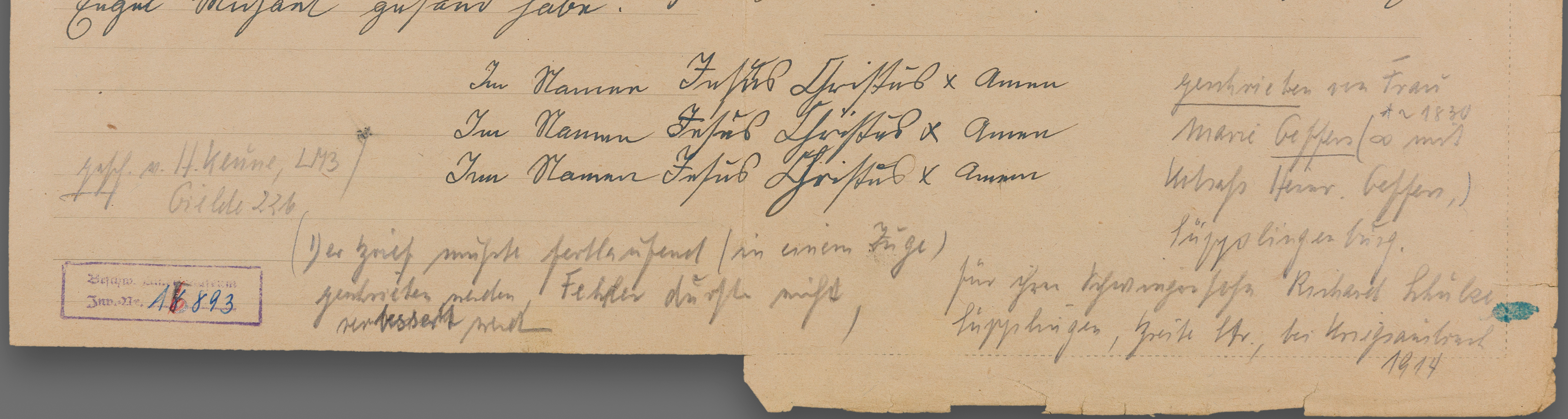

The rules concerning the writing or wearing of an effective amulet were not only found in the text itself but were passed on either orally or in writing. This is the case with the present example. On the back of the amulet are notes written in pencil as well as the stamp (‘Brschw. Landesmuseum Inv. Nr. 15893’) indicating the inventory of the state museum in Braunschweig where this Letter from Heaven is still held. The pencilled note reads as follows (Fig. 4):

geschr. v. H. Keune LMB Gielde 221 (Der Brief musste fortlaufend in einem Zuge geschrieben werden, Fehler durften nicht verbessert werden), geschrieben von Frau Marie Geffers (*~1830 ∞ mit Kotsaß Heinr. Geffers,) Süpplingenburg. für ihren Schwiegersohn Richard Schulze, Süpplingen, Breite Str., bei Kriegsausbruch 1914.

written by H. Keune LMB Gielde 221 (The letter had to be written in a single sitting, mistakes were not to be corrected), written by Mrs Marie Geffers (*~1830 ∞ with Kotsaß Heinr. Geffers,) Süpplingenburg. for her son-in-law, Richard Schulze, Süpplingen, Breite Strasse, at the outbreak of war 1914.

This note, written by Heinrich Keune (1906‑1994), a former employee of the museum, offers further information about how a Letter from Heaven was produced and how it should be handled: in another note, found in the book in which receipt of the Letter from Heaven is recorded, Keune adds that Schulze kept it on his person throughout the war. These days, there are many references to heavenly letters in various traditional collections and archives, because collectors of such traditional artefacts have accumulated these letters as well as reports on how they were produced and used, and how effective they were. The amulet and the knowledge of how to take care of it was passed on within the family – as was the example under discussion. Richard Schulze was the uncle (on the mother’s side) of Heinrich Keune who thus received the letter together with information – passed on orally – concerning the rules of copying and wearing such an amulet.

It is clear that Marie Geffers followed the rules of copying the letter without putting the pen down and without correcting any of her own or former mistakes. This practise draws attention to the central role of writing by hand regarding the efficacy of the Letter from Heaven. Writing by hand was meant to sustain the magical protective power of the letter, and each new copy was understood to have been written by God himself. In this way, Marie Geffers took on the role of a medium – writing God’s word – a role in which the act of writing became an act of empowerment. In this way she was able to obtain divine protection for her son-in-law – for his return, unscathed, from the war. Richard Schulze survived the war and brought the amulet home with him. The Letter from Heaven, together with the knowledge of its efficacy, remained with and was passed on within the family. Thus, it represents a widely accepted religious practise during the First World War.

References

-

Korff, Gottfried (Hrsg.) (2005), KriegsVolksKunde. Zur Erfahrungsbindung durch Symbolbildung, Tübingen: TVV.

-

Rohé, Jörg (1984), „Himmelsbriefe und Gredoria als Dokumente der Volksfrömmigkeit“, in Braunschweigische Heimat, 70, 63-79.

-

Stübe, Rudolf (1918), Der Himmelsbrief. Ein Beitrag zur allgemeinen Religionsgeschichte, Tübingen: Mohr.

-

Vanja, Konrad (2001), „Haussegen und Himmelsbriefe als Thema der Alltags- und Sonntagsheiligung und des Schutzes“, in Michael Simon (Hrsg.), Auf der Suche nach Heil und Heilung. Religiöse Aspekte der medikalen Alltagskultur, Dresden: Thelem, 37-62.

-

Wienker-Piepho, Sabine (2000), „Je gelehrter, desto verkehrter“? Volkskundlich-Kulturgeschichtliches zur Schriftbeherrschung, Münster u.a.: Waxmann.

Description

Braunschweigisches Landesmuseum

Shelfmark: LMB 15893

Material: A mass-produced letter for writing to the front

Size: 30,5 × 21,5 cm

Origin: Süpplingenburg, 1914

Copyright Notice

Copyright of illustrations and photographs:

© State Museum in Braunschweig, A. Pröhle

Reference note

Theresa Müller, 'Just as Christ stood pacified in the olive garden, all weapons shall be pacified.' How Marie Geffers made her son-in-law invulnerable In: Wiebke Beyer, Karin Becker (eds): Artefact of the Month No 21, CSMC, Hamburg, https://www.csmc.uni-hamburg.de/publications/aom/021-en.html