Peeling Away the LayersThe Birth and Previous Life of a Byzantine Manuscript

The Birth and Previous Life of a Byzantine Manuscript

José Maksimczuk

It is Constantinople in about the year 1450. The physician Demetrius Angelus has just bound a small manuscript containing philosophical treatises. Before placing it on his bookshelf, he casts a glance at one of the last folios. His eyes are drawn to a note jotted down by a previous owner of that part of the book. Demetrius spends some time pondering over the note and the person who wrote it. Finally, he puts the volume in the bookcase, evidently unaware of the fact that centuries later scholars would refer to this volume as Oxford, Bodleian Libraries, Auctarium T.4.23. As with many of his manuscripts, Demetrius acquired the last part of the Auctarium second hand. Several layers of annotations in different scripts testify to an intense use of that section for over a century. Peeling away those layers, we can gather revealing insights into both the biography of the manuscript and its many Byzantine readers.

The Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

Our manuscript is a paper codex containing 191 folios, measuring 22 × 13.5 cm, and comprising three units. The first two were copied by Angelus around the middle of the fifteenth century; the third predates the other two and was written by an anonymous scribe in the first half of the fourteenth century. The first unit (fols 2–71) contains Aristotle’s On the Soul and History of Animals; the second (fols 72–124) is Plato’s Phaedo. Angelus copied these first two units possibly at the same time; however, the restarting of the quire numbering at fol. 72r suggests that they were originally two independent projects. The final unit (fols 125–191) comprises Porphyry’s Isagoge and Aristotle’s Categories, On Interpretation, and First Analytics I 1–7.

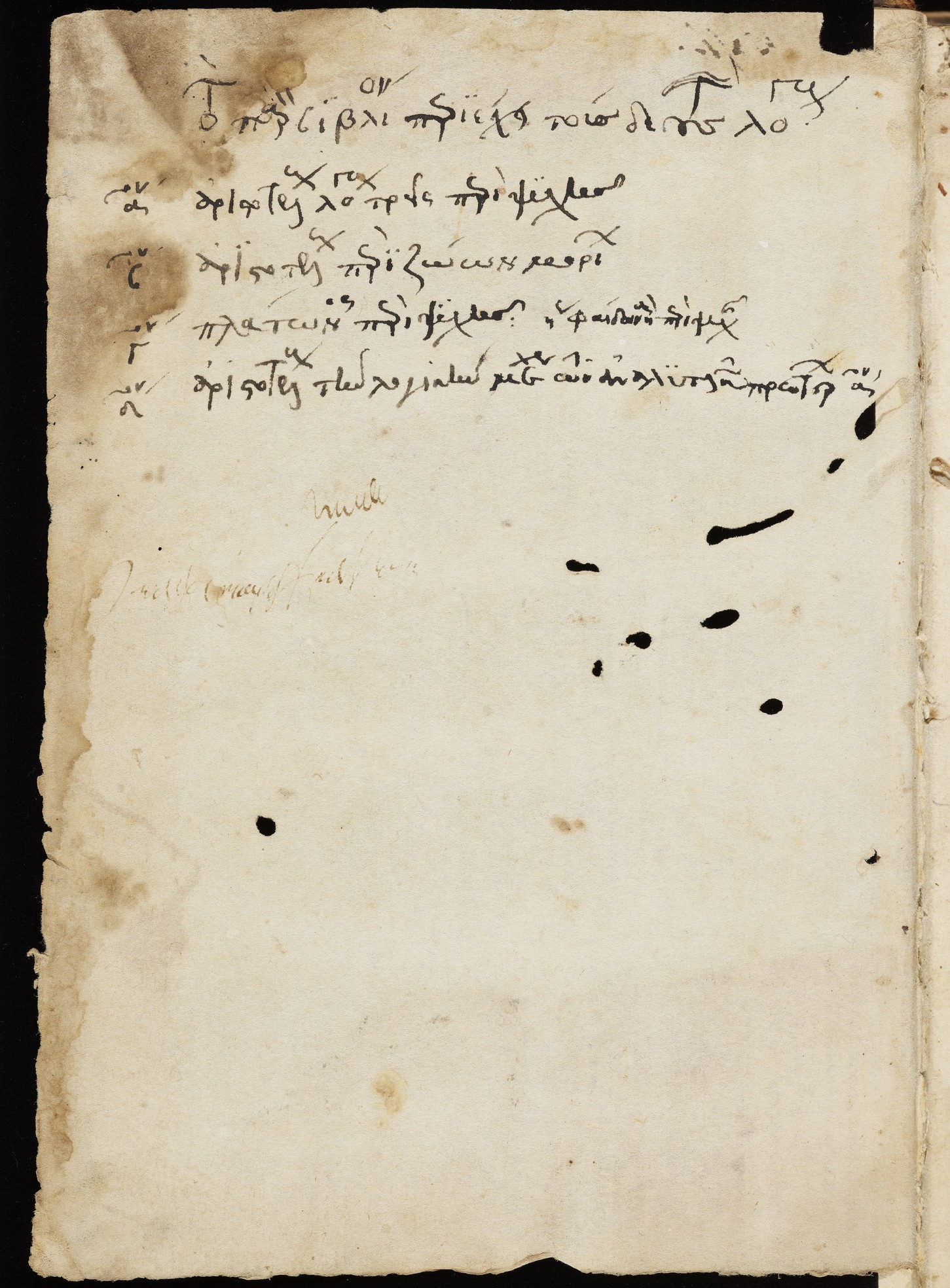

The fact that all three units have philosophical content may well be the reason for their being bound together. Evidence collected from other manuscripts informs us that Angelus worked at the Hospital of the Kral, which was attached to the Monastery of Prodromos in the Petra neighbourhood of Constantinople. It was in that hospital that he followed the lectures on Aristotelian logic given by the Byzantine teacher John Argyropoulus (1393/1394–1487) in about the year 1450. Against this background, our manuscript can be judged from a new perspective, namely that it is the book of a physician who studied logic. While the first two units contain physiological and scientific treatises, the third offers the first part of the Organon, namely the collection of Aristotle’s logical treatises (to which Isagoge was normally prepended). Furthermore, in addition to the fact that this volume would have been very appropriate in Angelus’ library, there is compelling evidence that he did indeed bind the three units together: on the verso of the first written folio (fol. 1v) one finds a table of contents, copied by Angelus himself (Fig. 1).

The table includes four entries (αον–δον = 1st–4th). The first two entries correspond to the contents of the first unit (Aristotle’s On the Soul and Parts of Animals); the third entry details the content of the second unit (Plato’s Phaedo), while the fourth lists the contents of the third unit (Aristotle’s Organon). Thus, we conclude that our manuscript was assembled by Angelus.

The Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

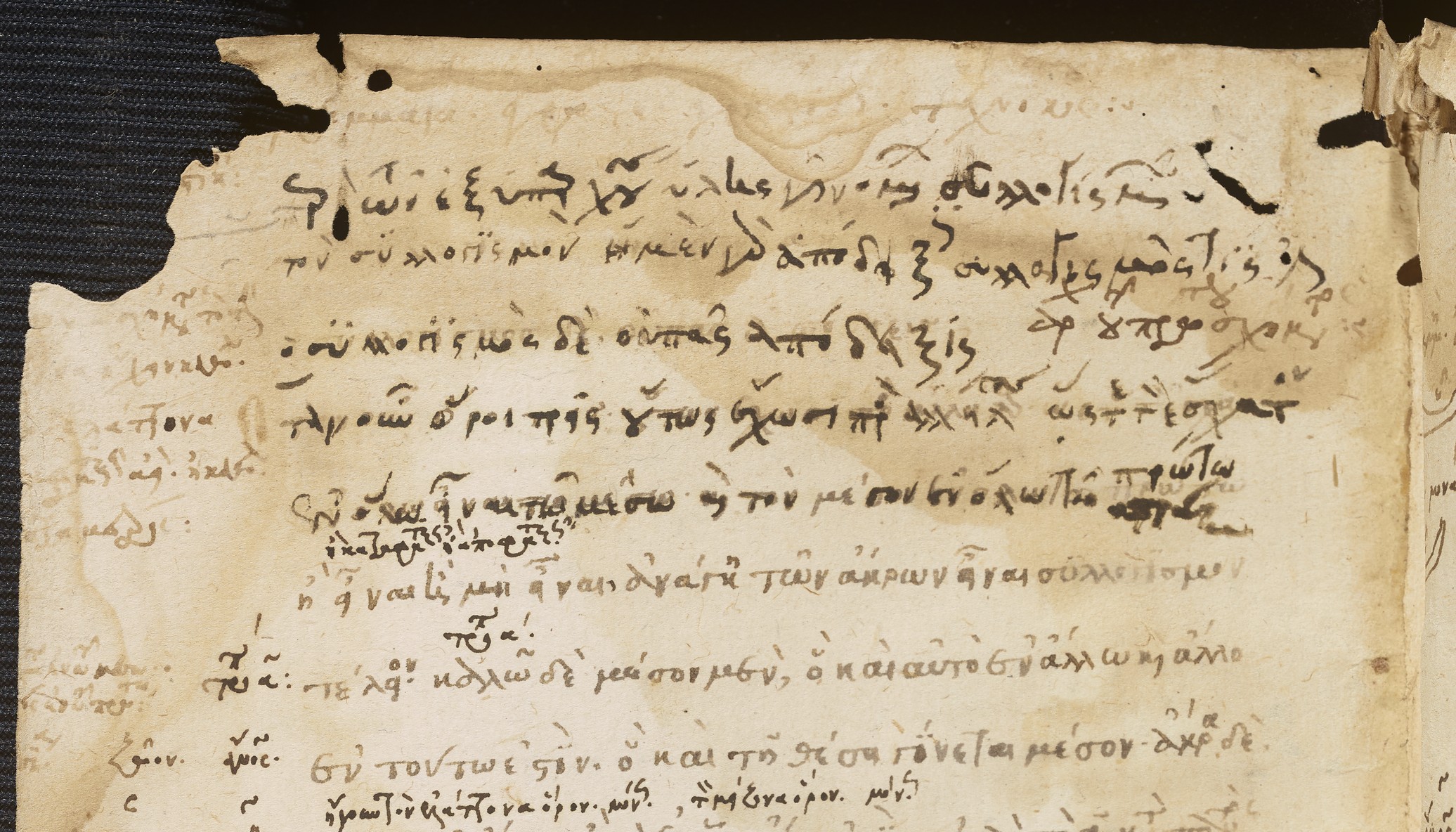

When Angelus acquired the fourteenth-century unit, it must have been in bad shape. He restored it by rewriting portions of the core text where the ink had faded (Fig. 2) and by adding some missing titles (Fig. 3).

The Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

While the annotations found in the first two units were almost all made by Angelus, the third – and oldest – unit in the codex shows clear indications of having been used by former readers. What do these annotations tell us about the oldest unit and about the individuals who read it?

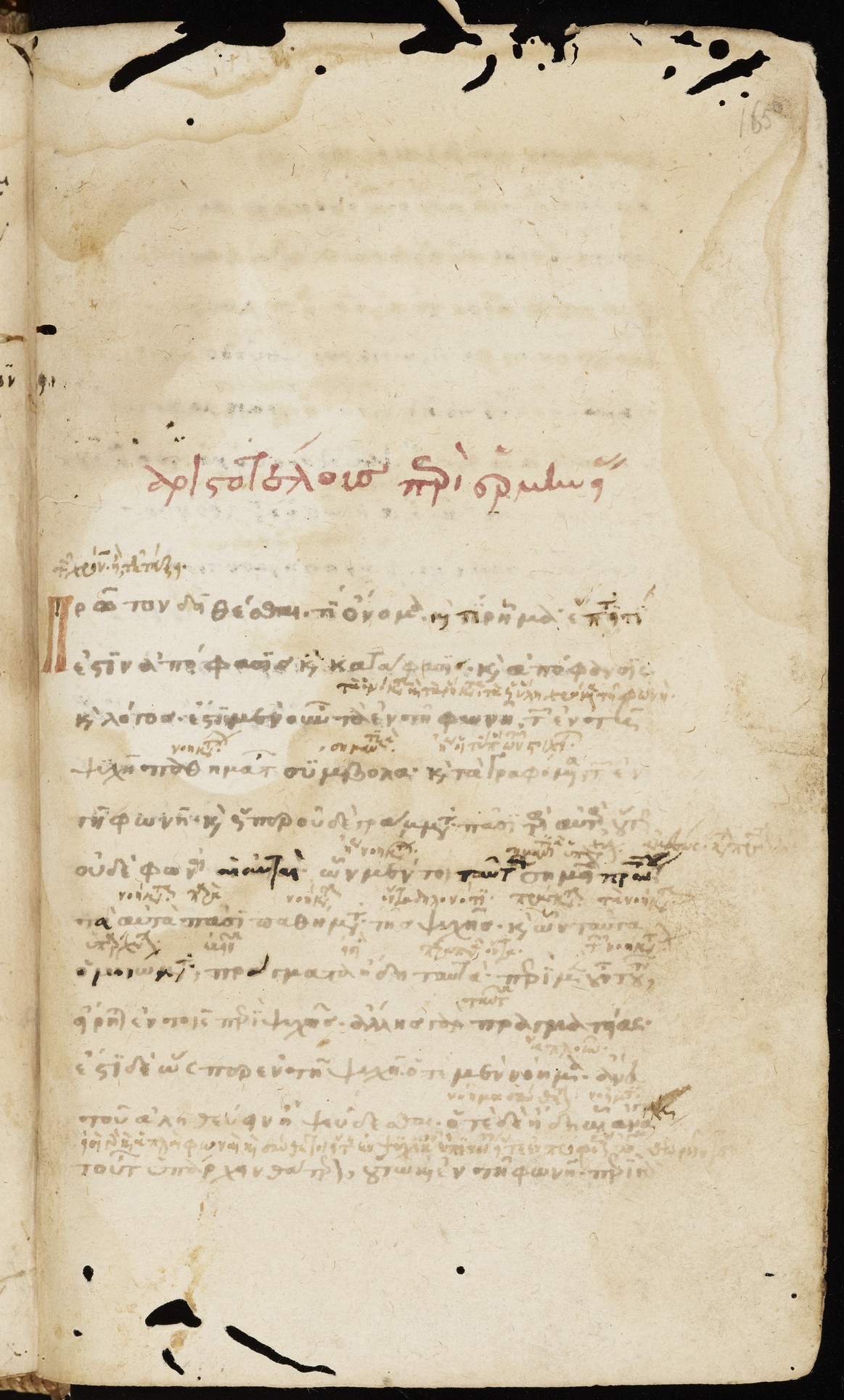

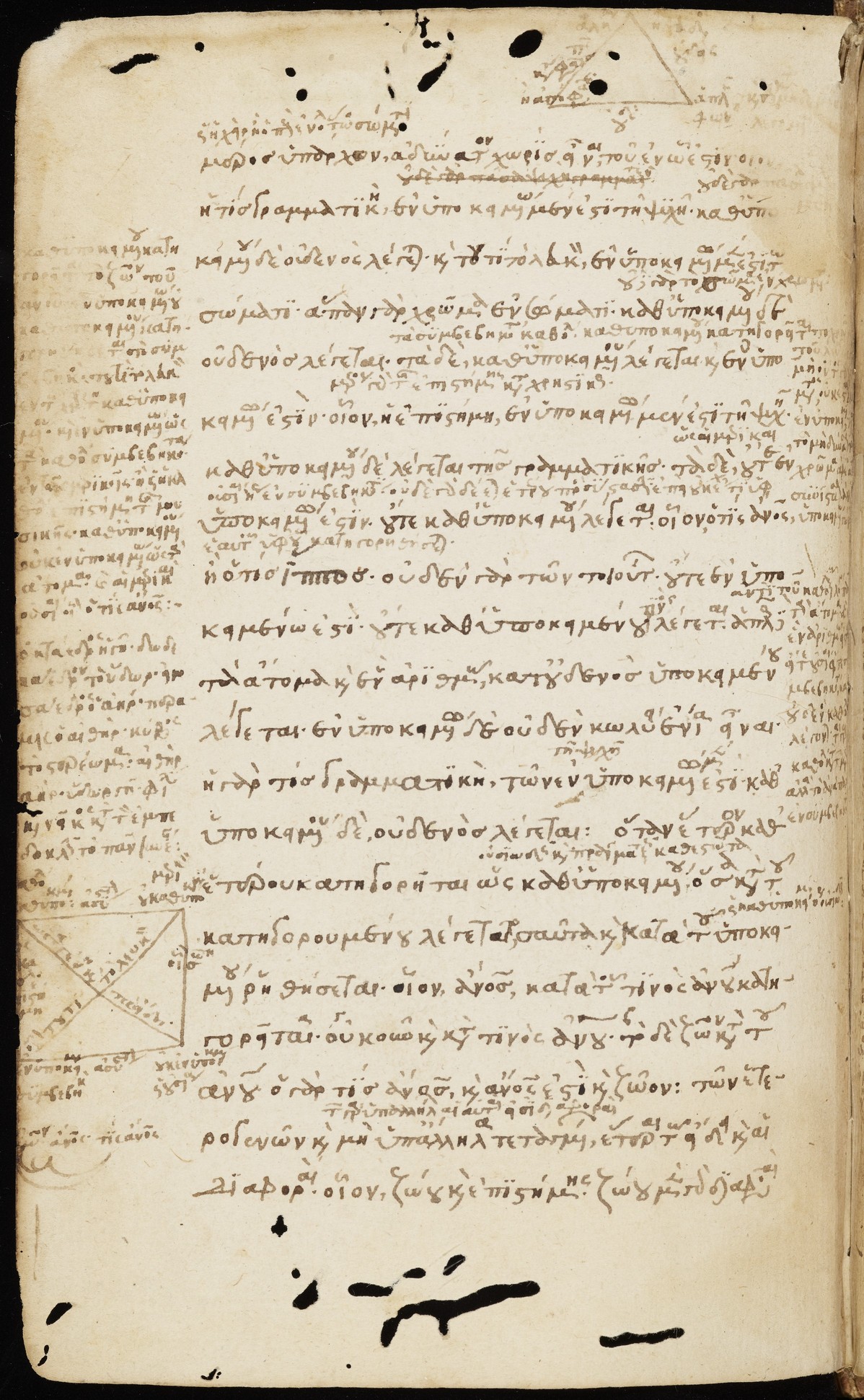

The writing in the third unit was evidently made by three hands, Hands A, B and C. Hand A appears to have copied the unit for his own use, a conclusion which is suggested by some later notes that he inserted in the last two folios (fols 190v–191v) and which are thematically unrelated to the general content of the unit (e.g. a list of Roman emperors). As is the case with many Organon manuscripts, this unit contains an exegetical apparatus consisting of notes copied by Hand A both in the margins and between the lines of the core text (Fig. 4); most of these notes have parallels in earlier commentaries on Aristotle. Given the fact that the portion of the Organon found in this unit was used to study logic in Byzantine schools it is quite likely that Hand A made this unit for study purposes.

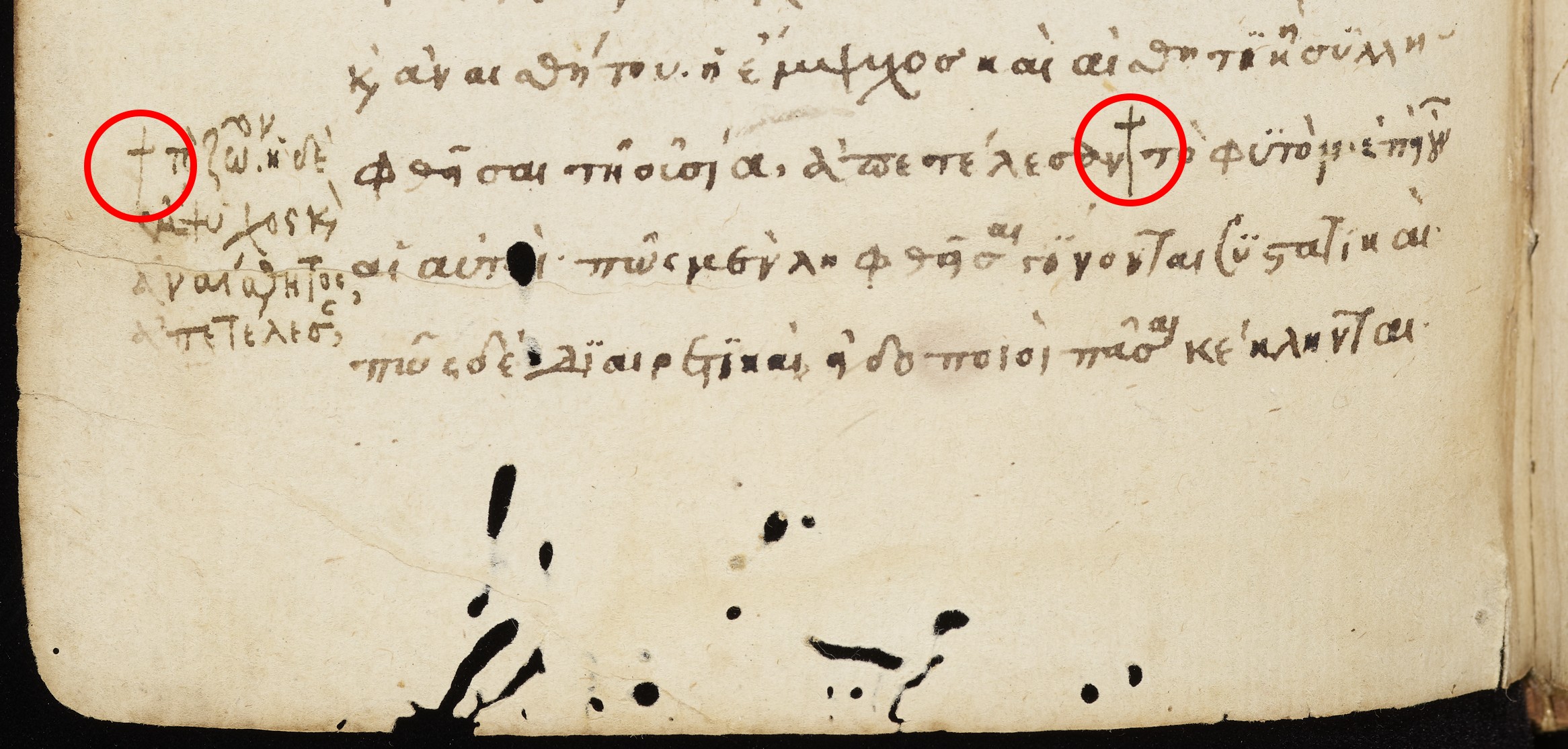

Following Hand A, two other individuals, Hand B and Hand C, used the unit in the second half of the fourteenth and the beginning of the fifteenth century, respectively. They improved the core content of the unit by comparing it with the text of other manuscripts of the Organon. Fig. 5 shows Hand B’s addition of an original line from Isagoge omitted by Hand A. Hand B made cross-shaped signs at the beginning of the marginal text and again in the middle of the core text to show where the supplement belongs.

The Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

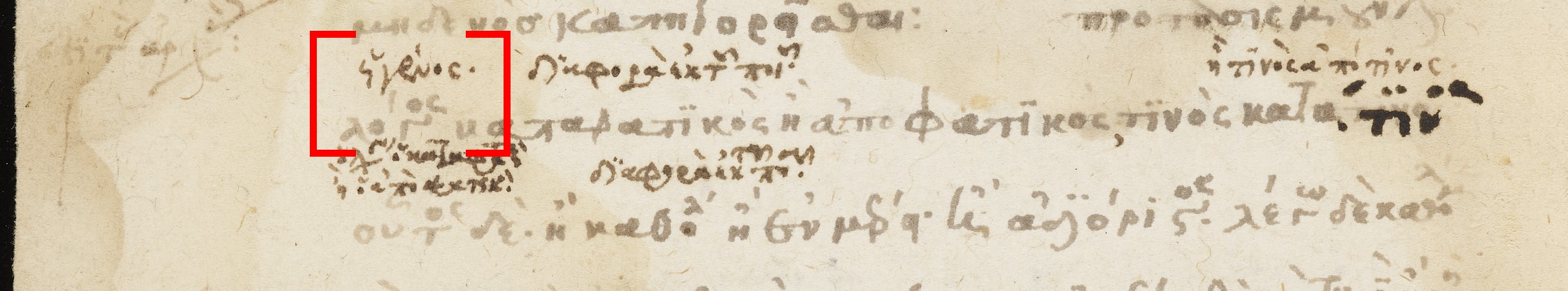

Hand B and Hand C made similar interlineal notes. Some of these notes offer short and simple explanations to a line, an expression, or a term in the core text; others provide additional information to the core text. A good example of the additional information is a note inserted by Hand C between the lines of fol. 181v (Fig. 6). At this point of the First Analytics, Aristotle defines ‘proposition’, one of the main components of a syllogism. Aristotle states: ‘πρότασις μὲν οὖν ἐστὶ λόγος καταφατικὸς ἢ ἀποφατικὸς τινὸς κατά τινος’ (‘Proposition, then, is an affirmative or negative sentence of something about something’). Above the word λόγος (sentence), Hand C wrote ‘ὡς γένος’ (‘as genus’), indicating that, here, Aristotle understands ‘sentence’ as a genus under which different species are subsumed (assertoric, interrogative, etc.). The ultimate source of this note is the sixth-century commentary of John Philoponus. The note is identically contained in older manuscripts of the First Analytics (e.g. Milano, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, M 71 sup., fol. 49r); Hand C must have copied it from an unidentified manuscript he used to upgrade our unit.

Although both Hand B and Hand C followed the practice of Hand A when adding marginal notes, nevertheless, there are substantial differences in the way each user annotated the unit. For instance, Hand B inserted marginal notes which summarise the discussion held in the core content of the manuscript: in fol. 126v we find the following note inserted by Hand B in the outer margin: ‘τὰ ἔχοντα θέσιν δεῖ εἶναι καὶ αἰσθητὰ καὶ κεῖσθαι ἐν τόπῳ τινὶ καὶ ὑπομένειν τὰ μόρια ἤτοι σώζεσθαι καὶ μὴ διεφθάρθαι τούτων τινά’ (‘It is necessary that things that have a position are perceptible and are situated in a place, and that their parts endure or some of them are preserved and not decomposed’); in this note Hand B recapitulates part of the sixth chapter of the Categories, condensing in one sentence the essentials of the discussion on position (θέσις) in Categories ch. 6. Such a note has no parallels in the known late-antique and Byzantine commentaries on the Categories, and its basic content and simple syntaxis suggest that it was spontaneously jotted down by Hand B while reading the treatise.

The Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

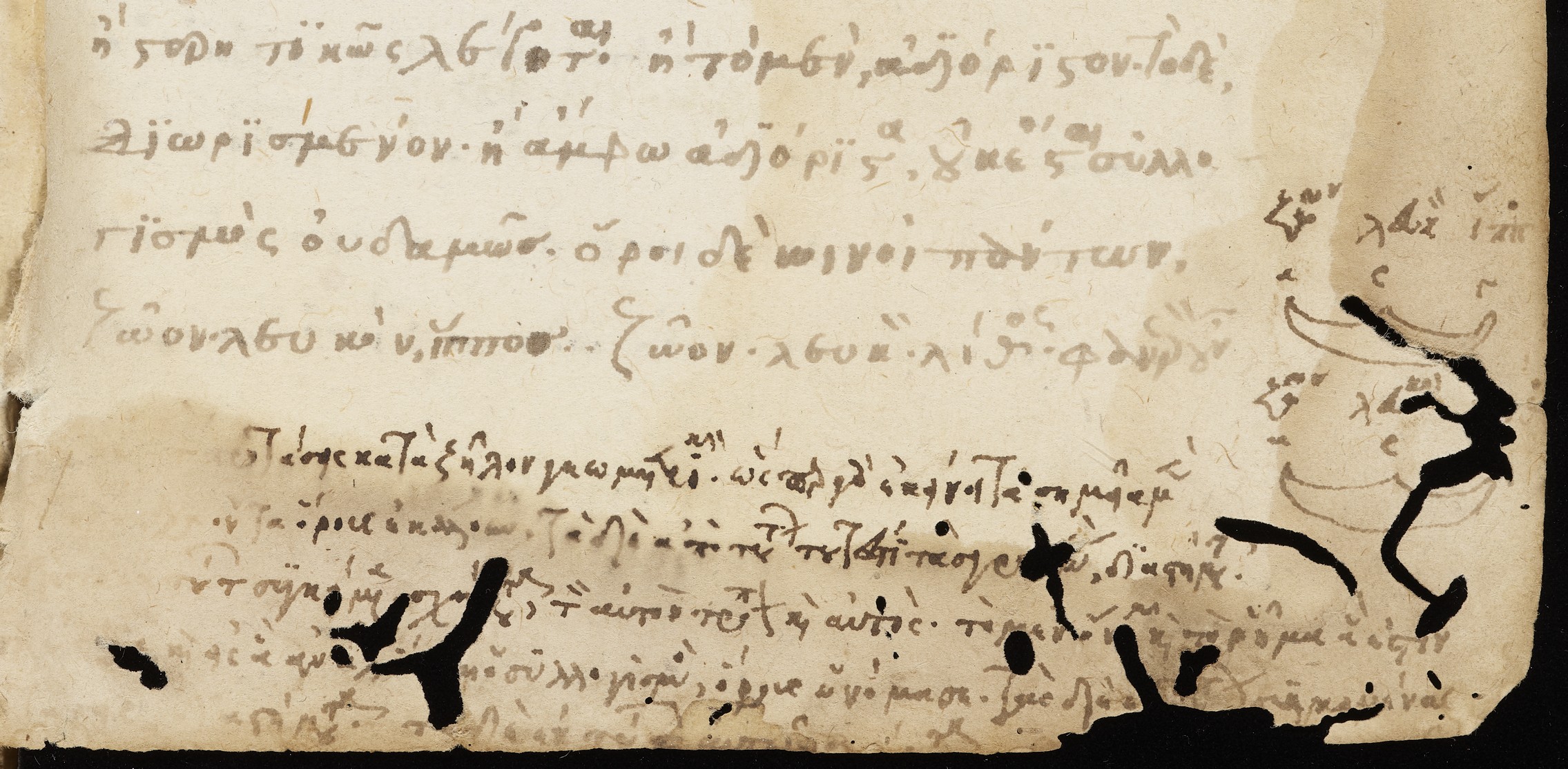

Hand C’s marginal notes are more complex. They are longer exegetical texts copied from other sources and inserted with the aim of shedding new light on the core content. An example of this is found in the lower margin of fol. 186v (Fig. 7). Although some portions of the note are illegible today, it can be identified as a citation from John Philoponus’ Commentary on the First Analytics. Unfortunately, the manuscript from which Hand C copied the note cannot be identified, however, it is likely that he found it in the margins of the manuscript he used to ameliorate the core text of the unit. Despite the differences in the ways in which Hand B and Hand C inserted annotations, they shared the same approach, and both intended to upgrade the unit – correcting the core text and adding explicative notes both in the margins and between the lines. The fact that both used a manuscript containing the ‘school format’ of the Organon would suggest that they used the unit as their textbook of logic.

The Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

This investigation of layers helps us to reconstruct different stages in the life of our manuscript – in what we might call its prehistory, namely, the adventurous life of its last unit; this phase ended when Angelus created the composite in which it is found to this day. Although it is no longer possible to trace the names and occupations of Hand A, Hand B, and Hand C, or the exact circumstances under which they used the final unit of our manuscript, examples of the way they copied, read, and annotated manuscripts survive in the many layers of the Oxford codex.

The Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

References

- Coxe, Henry O. (1883), Catalogi codicum manuscriptorum Bibliothecae Bodleianae pars prima recensionem codicum Graecorum continens, Oxonii: e Typographeo Academico [repr. Oxford: Express Litho Service, 1969], 808.

- Maksimzcuk, José (2022), ‘Demetrius Angelus’ Two Volumes of Aristotle’s Organon: A Multi-layered Set’, Jahrbuch der Österreichischen Byzantinistik, 72 (forthcoming).

- Mondrain, Brigitte (2000), ‘Jean Argyropoulos professeur à Constantinople et ses auditeurs médecins, d’Andronic Eparque à Démétrios Angelos’, in Cordula Scholz and Georgios Makris (eds), ΠΟΛΥΠΛΕΥΡΟΣ ΝΟΥΣ. Miscellanea für Peter Schreiner zu seinem 60. Geburtstag (Byzantinisches Archiv, 19), Munich/Leipzig: Saur, 223–250.

- Mondrain, Brigitte (2010), ‘Démétrios Angelos et la médecine : contribution nouvelle au dossier’, in Véronique Boudon-Millot, Antonio Garzya, Jacques Jouanna and Amneris Roselli (eds), Storia della tradizione e edizione dei medici greci. Atti del VI Colloquio internazionale, Paris 12–14 aprile 2008 (Collectanea, 27), Napoli: D’Auria, 293–322.

Description

Location: Oxford, Bodleian Libraries

Shelfmark: Auctarium T.4.23 (Misc. 261)

Date: first half of the fourteenth century and middle of the fifteenth century

Material: paper

Size: c. 22 × 13.5 cm

Provenance: Constantinople

Copyright Notice

Copyright: The Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

Reference note

José Maksimczuk , Peeling Away the Layers: The Birth and Previous Life of a Byzantine Manuscript In: Wiebke Beyer, Karin Becker (eds): Artefact of the Month No 20, CSMC, Hamburg, https://www.csmc.uni-hamburg.de/publications/aom/020-en.html