‘Heckling from the left: Absolutely correct’

Shorthand notes in parliament

Hannah Boeddeker

Comprehensive, correct, word-for-word – that was the standard expected of parliamentary transcripts in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In effect, these published reports were the official, legally binding records which gave the public the possibility of keeping itself informed about parliamentary debates. But how was it possible to fulfil such high demands before the invention of the tape recorder? The answer is: stenography or shorthand. Quite simply, shorthand is a writing system which, using abbreviations, allows the spoken word to be written with remarkable speed. The manuscript under discussion – parliamentary shorthand notes from the early twentieth century – reveals the additional strategies and tricks which were needed to do justice to the exigencies of stenography.

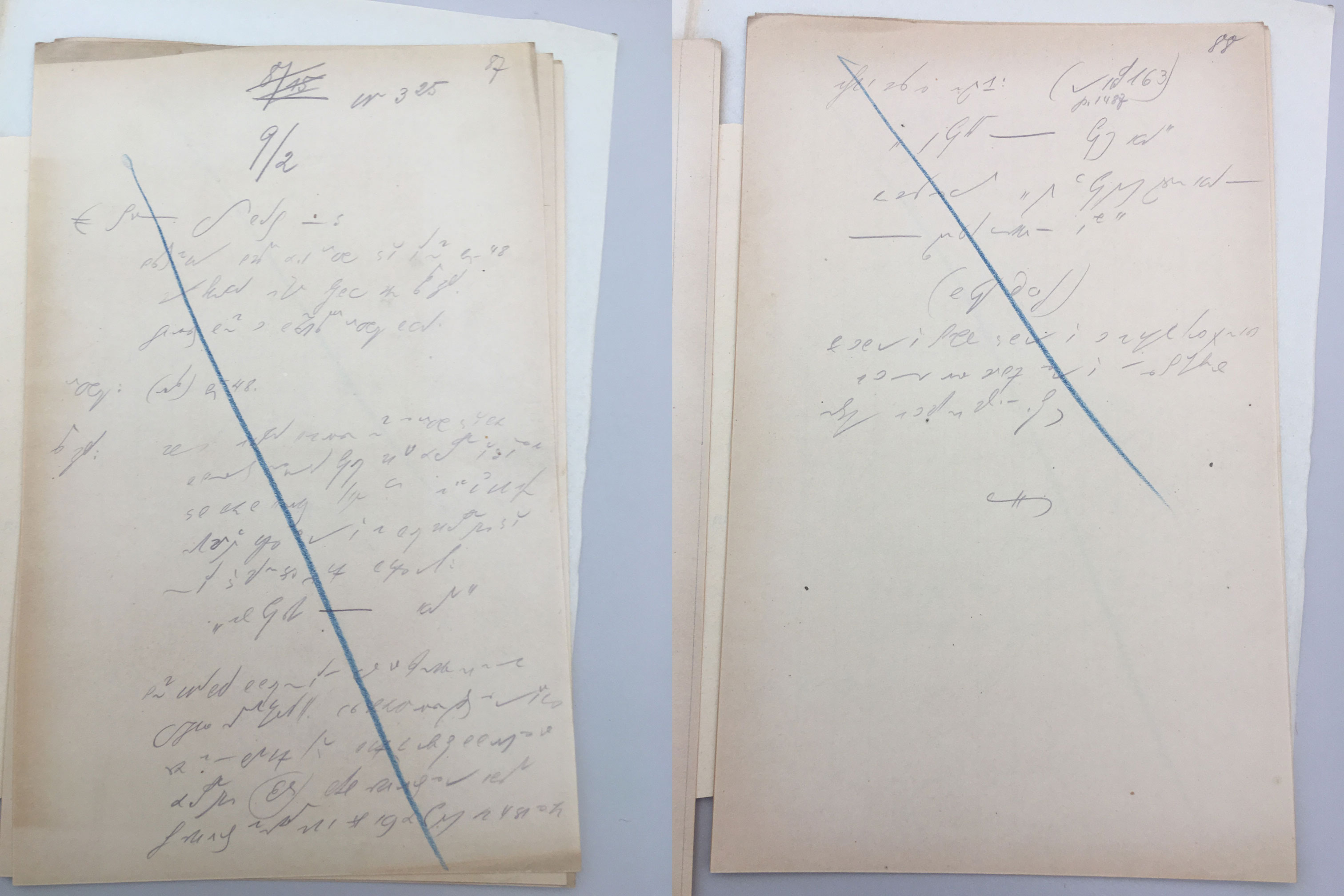

This parliamentary shorthand from the parliament of the Free State of Mecklenburg-Schwerin in 1920 contains an extract of the ninth plenary session of the parliament from 8 October 1920. The manuscript comprises two sheets of white paper, each approximately DIN A5. The shorthand is written in pencil on these two sheets with generous spacing. The text was later crossed out with blue diagonal lines (Fig. 1). All the shorthand notes of the sittings – as well as the written and the printed versions of the transcript – belong in the official state archives of the Schwerin parliament.

H. Boeddeker

The shorthand used in German parliaments originated about a hundred years before the notes described here were made; thus, our manuscript belongs in a tradition which goes back to the time of constitutionalism in the early nineteenth century. The first state parliaments to employ stenographers were Baden, Bavaria and Württemberg 1818/1819. By 1848 there were at least nine German assemblies employing ‘Geschwindschreiber’ (English: rapid writers), most of whom worked in pairs to record the debates. The next step saw the stenographers dictating their shorthand notes to secretaries who originally wrote in long hand, and later with a typewriter. Finally, the transcriptions were checked by members of parliament before they were printed and published. Following the ‘November Revolution’ (1918/1919) parliaments became more important in the German political system, and further state parliaments employed stenographers. One such was the Free State of Mecklenburg-Schwerin.

In 1919 the State Parliament of Mecklenburg-Schwerin employed the stenographers Walter Dobermann and Herbert Scheidhauer. At that time, parliamentary shorthand writers were expected to satisfy certain criteria: they had to have an academic education in order to understand the content of the debates, and they had to be physically fit because the work was physically demanding. Both Dobermann and Scheidhauer had studied and thus satisfied the first criterion. However, in 1925, Scheidhauer had to take a short break because the strain of the work had led to a breakdown. The shorthand notes produced by Dobermann and Scheidhauer are one of the rare examples which were systematically filed in the archives. In many state parliaments these notes were destroyed after the protocols had been printed; the former were no longer felt to be of use. Many of the characteristics of the notes under discussion were typical of parliamentary shorthand notes, and, indeed, were detailed in the official instructions.

H. Boeddeker

The present shorthand note is written with pencil on unlined paper. If the appearance of the manuscript seems to be somewhat haphazard, it must be said that the choice of pencils and paper – the tools of the trade – was certainly not random. The most important criterion here was that the material allows an undisturbed and rapid flow of writing, so that the stenographer should not miss a single word of what the speaker said. Pencils have the advantage over ink that they do not smudge the paper. Furthermore, one no longer needs the time to move the arm between paper and inkwell. In the early nineteenth century, the paper used for shorthand was a kind of parchment which was as thick and firm as cardboard, and whose surface was especially smooth. By 1929 shorthand pads had been specially developed in which the spaces between the lines were particularly suitable for the abbreviations used in shorthand. However, in the present manuscript the paper used by Dobermann and Scheidhauer was unlined; the reasons for this are not known.

The separate sheets were placed together in an envelope in which all the shorthand notes written by a stenographer during any one session were collected. However, Dobermann and Scheidhauer did not work together during a whole session, rather, they took turns. The short intervals of mostly ten to thirty minutes were intended to help the stenographers keep their concentration. The session and rotation numbers were marked on the outside of the envelope containing the shorthand notes (Fig. 2). In the present case, the ‘9’ refers to the ninth plenary session of the parliament, and the smaller ‘2’ and ‘4’ indicate the rotation of the stenographers during the ninth session. Additionally, the day’s agenda was noted on the inside of the envelope so that the notes of the given session could be documented (Fig. 3). In the present case one can see that the sheet of paper was prepared for a previous session: at the top of the page we see the numbers ‘8/15’; however, since it has been crossed out, it was apparently not needed. The session and rotation numbers were also noted in the longhand transcription; in this way the possibility of tracing any given speech was constantly guaranteed (Fig. 3).

H. Boeddeker

The numbers ‘3:25’ can be seen in the top right corner of the first sheet, marking the time at which the session began (Fig. 4); in the same corner the date and the name of the stenographer are sometimes noted. Since this information is not given in the present case we cannot know whether Dobermann or Scheidhauer made these shorthand notes. The number ‘87’ seen in the top right-hand corner was probably added later and marks the number given these notes in the archive – where a number of envelopes containing shorthand notes of the 1920 sessions are collected. The names of the speakers were marked in the same way as in a theatre script: they are found on the left preceding the relevant paragraph, allowing for a quick overview. The pages of the notes under discussion are crossed out with blue diagonal lines indicating that the shorthand had been transcribed with a typewriter.

In the shorthand notes described here a special kind of shorthand was used – a kind specifically designed to be used in such hearings: German ‘Debattenschrift’ (lit. ‘debate script’) and ‘Kammerstenographie’ (lit. ‘chamber shorthand’). In this type of shorthand words and whole sentences could be radically abbreviated in order to retain what was said in the often heated debates. For instance, prefixes and suffixes might represent a whole word, with the consequence that these prefixes and suffixes could represent a number of different words. Thus, when transcribing, context, logic and memory played an important role for the stenographers. In the notes under discussion we see that terms which were frequently used in parliament are markedly abbreviated, e.g. ‘deputy’, ‘colleague’ and the phrase ‘ladies and gentlemen’.

H. Boeddeker

Thus, the stenographers did not only record speeches, they also noted interruptions such as heckling, applause or disagreements. Consequently the demand for accuracy implied more than simply recording the speeches. The stenographers’ job was to record everything. Recording hecklers, however, was very difficult; their comments came without any warning and the speaker had to be identified. It is thus not surprising that the words actually used were written in the shorthand notes, e.g. ‘Absolutely correct!’ During the writing of the transcription the stenographer had to remember the details and add: ‘Heckling from the left: Absolutely correct.’

H. Boeddeker

Occasionally the stenographers could put the pencil to one side. This was possible when the deputies read something: for example, when they quoted a newspaper article, a legal text or other written documents. Since a written version already existed in such cases the stenographer only recorded the beginning and end of the quote, and it was the duty of the deputy to give a copy of the text to the stenographer afterwards so that it might be included in the transcription. Two examples of such quotes can be found in the shorthand notes of Schwerin. When a court decision was quoted only the beginning of the quote is recorded: ‘In the criminal case’; the final judgment is recorded in the transcription. A similar indication is given on the first page where we read: ‘Dpty Wendorff (reads out) typescript 48’. A facsimile of the typescript was then pasted into the transcription (Fig. 5).

The shorthand notes described here – and parts of the transcription – show just how difficult it was for the stenographers to produce a faithful protocol; they also indicate the techniques the stenographers used to record the speeches of the individual deputies, and to arrange the transcriptions in the sequence in which they were made. In fact, the rather unexceptional shorthand notes are the product of a very challenging writing technique, and the session and rotation numbers indicate just how complicated the whole process was: the transcription, the correction and the printing that followed the shorthand. All of this was necessary for the publication of a faithful protocol, one which was part to fulfilling the of a parliamentary public.

References

- Burkhardt, Armin (2003), Das Parlament und seine Sprache. Studien zu Theorie und Geschichte parlamentarischer Kommunikation, Tübingen: Niemeyer.

- Inachin, Kyra T (2004), Durchbruch zur demokratischen Moderne. Die Landtage von Mecklenburg-Schwerin, Mecklenburg-Strelitz und Pommern während der Weimarer Republik, Bremen: Edition Temmen.

- Johnen, Christian (1928), Allgemeine Geschichte der Kurzschrift, Berlin: Schrey.

- Olschewski, Andreas (2000), ‘Die Verschriftung von Parlamentsdebatten durch die stenographischen Dienste in Geschichte und Gegenwart’, in: Burkhardt, Armin (ed): Sprache des deutschen Parlamentarismus. Studien zu 150 Jahren parlamentarische Kommunikation, Wiesbaden: Westdeutscher Verlag, 336-356.

Description

Landeshauptarchiv Schwerin

Shelfmark: LHAS 5.11-2 281 (Shorthand notes), LHAS 5.11-2 298a (Transcription)

Material: Paper, pencil, blue pencil

Source: Schwerin 1920

Copyright Notice

Copyright: Landeshauptarchiv Schwerin. Photos by Hannah Boeddeker.

Reference note

Hannah Boeddeker, ‘Heckling from the left: Absolutely correct’: Shorthand notes in parliament In: Wiebke Beyer, Karin Becker (eds): Artefact of the Month No 19, CSMC, Hamburg, https://www.csmc.uni-hamburg.de/publications/aom/019-en.html