All that remains

A Painting with Inscriptions

Uta Lauer

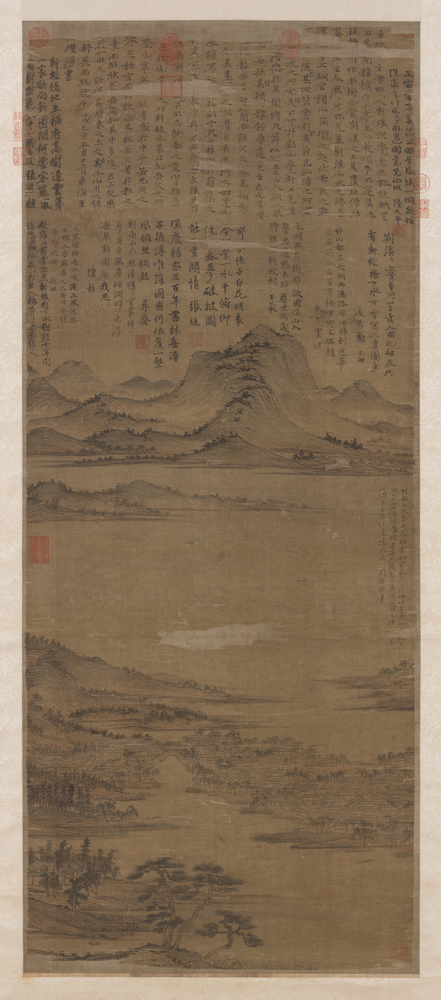

A hanging scroll depicting a small town in an idyllic landscape of lakes and gently rolling hills – it seems to be nothing more than a charming, albeit somewhat bland, Chinese painting. Yet, it tells a story of disaster and loss, of the burning of a library, and the looting and destruction of an art collection. Twelve signed inscriptions and numerous seals on the painting tell a tale of shared grief, of loyalty and friendship, and, finally, of appreciation and commemoration.

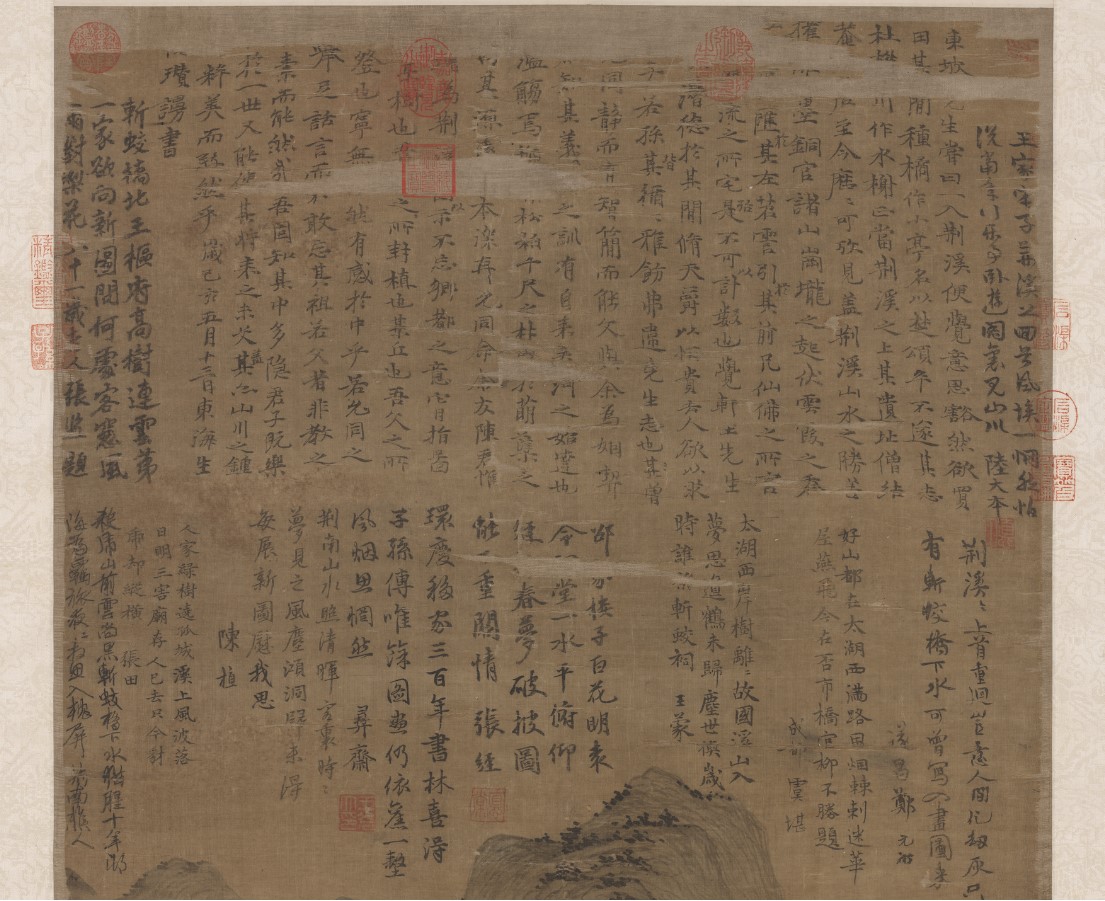

The painting bears the title Picture of Jingxi 荊溪圖. It is done in ink on silk and mounted as a hanging scroll, measuring 129 × 52.7 cm. The picture shows the town of Jingxi (modern day Yixing 宜興, Jiangsu province) on the west bank of Lake Tai, and is neither signed nor sealed by the artist, but the upper third of the hanging scroll is filled with eleven inscriptions, all of them signed and three of them impressed with the personal seal of the colophon writer. One additional inscription is written directly into the pictorial space to the right of the painting. In the fourteenth century, it was common practice among literati-scholars to write colophons on paintings in order to record themselves in the socio-cultural history of the artefact.

There are two dates in two separate inscriptions. One refers to the year 1359 and the other can be deduced from the line Inscribed by the old man aged 81 sui [years], Zhang Jian to 1361 (biographical information on Zhang Jian 張監 tells us that he lived from 1281‒1370).

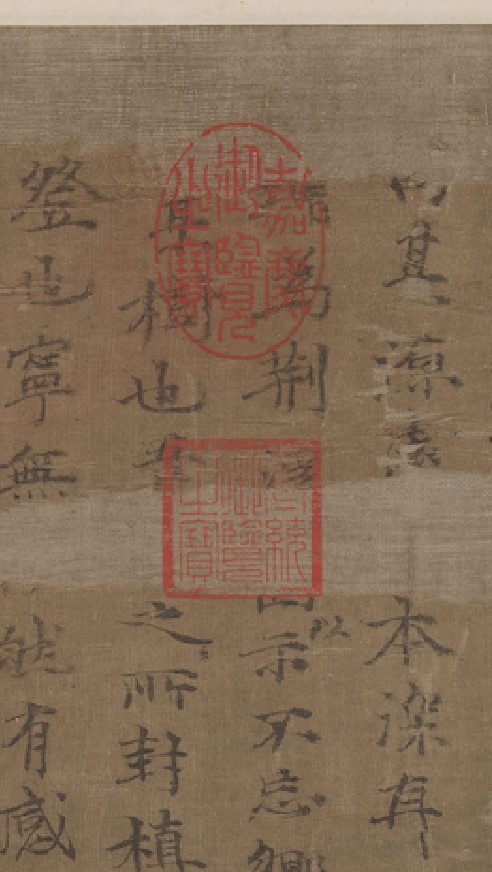

Ten seals by three emperors are prominently impressed on the upper part of the scroll. Only one imperial seal is imprinted directly on the picture at the left-hand side, nicely balancing an inscription to the right. Remnants of two more collectors’ seals are visible but they are so badly damaged that they have become illegible. In some parts, the silk of the scroll has suffered serious damage, especially at the top, i.e. at the outer layer which is most exposed when the scroll is rolled up. From the layout of the artefact, with the lower two thirds consisting of the painting and the top third cramped with inscriptions, it is obvious that the top part was deliberately left blank, leaving space for the inscriptions.

Closer observation of the painting reveals that the town is completely depopulated. In the middle of the lake two people are rowing away from Jingxi. What has happened, what is all this about? To answer that question, one must turn to the contents of the inscriptions and to the identity of the colophon authors. The earliest inscription on the painting is a lengthy record in the middle of the scroll, in the upper third. Several characters are missing, but the date is visible towards the end of the inscription, fifth month of the yihai year [1359], as well as most of the signature, casually written by Donghai-born/missing character/Zan; the latter refers to the literati painter and poet Ni Zan 倪瓚 (1301‒1374). Despite the damage, the colophon can be re-constructed from the published works of the author where the text is recorded as Inscription on Picture of Jingxi, painted by Chen Weiyun.

Chen Weiyun is the sobriquet of Chen Ruyan 陳汝言 (ca. 1331‒1371), a young amateur painter and friend of Ni Zan. He painted the scenery on behalf of Wang Yuntong 王允同, a descendant of a prominent Jingxi family who had owned a vast library and a substantial art collection prior to the destruction of the city. In his inscription Ni Zan recalls the catastrophe, observing that this commission served as a means of showing that he [Wang Yuntong] had not forgotten the essence of his place of birth.

In the 1350s, natural disasters like floods or crop failure, combined with dramatically increased tax demands on landowners and forced labour, led rebels to take up arms against the loathed, foreign Mongol rulers of China. The vicious, bloody fighting forced many families including the Wangs to flee their ancestral homes to the relative safety of pacified towns like Suzhou.

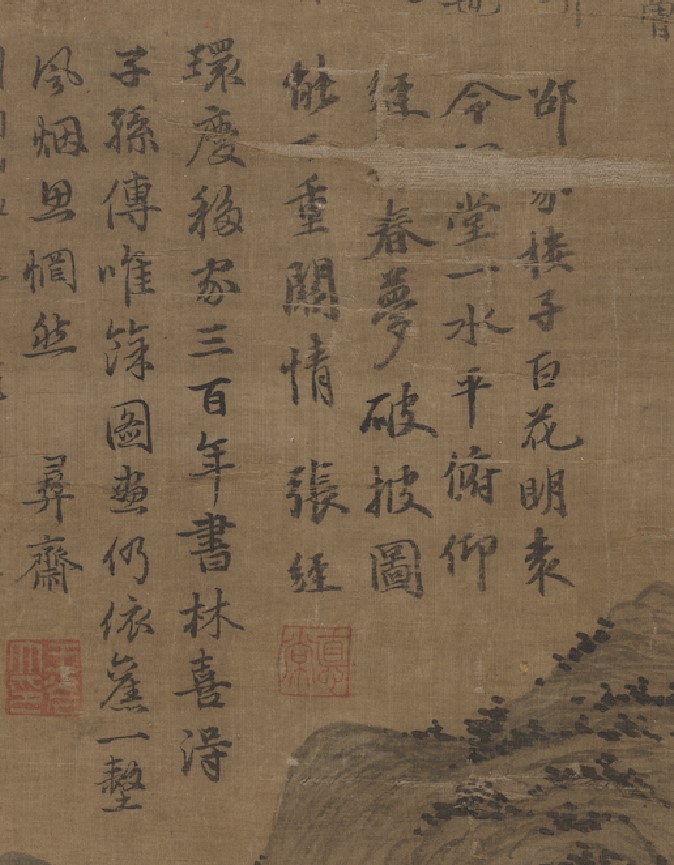

The author of the other dated colophon, the eighty-one-year-old Zhang Jian, was the private tutor of the Wang family in Jingxi. Along with his two sons, Zhang Jing 張經 and Zhang Wei 張緯, Zhang Jian had also fled to Suzhou. Zhang Wei followed in his father’s footsteps as teacher of the Wang’s younger generation, and the Zhang brothers were also close friends of Ni Zan. Both graced the Picture of Jingxi with inscriptions. Zhang Wei, not mincing his words, writes of the destruction and killing which devastated Jingxi: Before Mt. Shahu, the clouds are still black; beneath Zhanjiao Bridge, the water [reeks] like rotting meat.

His older brother Zhang Jing, adds a more nostalgic note, recalling the peaceful times: [my] spring dream is broken; [by] unrolling [this] picture, can I regain that emotion?

His signature is followed by a square relief seal, containing his sobriquet Dechang 德常.

Two more colophons bear seals: that of Lu Daben 陸大本 at the top right is a square intaglio seal with his personal name, Dezhong 德中; the one following Yi Zhai’s 彝齋 inscription to the left of Zhang Jing’s colophon, is a square intaglio seal reading Seal of Wang Guangda王光大印. This seal reveals the identity of Yi Zhai as Wang Guangda, father of Wang Yuntong, the patron who had commissioned this painting. Wang Guangda took the name Yi Zhai, Studio of the Yi [wine vessel], from an ancient bronze drinking vessel which had been handed down in the family. Because of its provenance, this wine vessel was a prized treasure: it had once belonged to the eleventh-century scholar, epigrapher, and calligrapher Ouyang Xiu 歐陽修 (1007–1072). Apparently, this was one of the very few objects from the family’s art collection that survived the looting and burning of their home. However, their book collection was destroyed during the fighting. Wang Guangda writes in his colophon:

By good fortune its libraries had been passed down through generations of sons and grandsons.

Now this painting is all that remains of them.

The remaining colophon authors were mainly known for their skills in poetry, as Daoist hermits and, in the case of Wang Meng 王蒙 (1308–1385), as a celebrated painter. All were born locally or, at least for some time, had taken part in cultural activities in the area, exchanging poems, writing calligraphy, or collecting rare books. Their colophons testify to their friendship and solidarity with the Wang family.

The Wang family is known to have returned to their family estate in Jingxi after ten years of exile in Suzhou. However, there are no visible markers on the scroll of what happened to the Picture of Jingxi between the mid-fourteenth century, when the painting was commissioned and the colophons were appended, and the late eighteenth century. It was only then that emperor Qianlong 乾隆 (r. 1735–1796) impressed eight seals on the artefact. Six of them are printed on the joint between the painting and the surrounding silk mounting. From their position, it can be deduced that the painting was re-mounted in the imperial workshop after it came into the emperor’s possession.

Finally, a rectangular relief seal reading Treasure examined and stored at Zhonghua Palace, is the only seal printed directly into the painted space at the middle left of the scroll; it provides an important clue as to the emperor’s appreciation of this painting. The Zhonghua Palace was part of emperor Qianlong’s private living quarters. It was there that he kept artefacts especially dear to him. Terms like viewed, examined and appreciated or ordered and examined, found in the legend of the seals impressed on this scroll, clearly point to detailed imperial attention.

Emperor Qianlong’s wish fitting for sons and grandsons, as expressed in the square intaglio seal second from the top on the left-hand side of the painting came true when his son the Jiaqing emperor 嘉慶 (r. 1796–1820) printed his oval relief seal in the top middle, slightly lower than his father’s – as a mark of respect. Not surprisingly, the painting received no attention for the next one hundred years as the Manchu empire struggled for survival. The final seal, a square relief seal reading treasure viewed by the Xuantong emperor was printed at the top of the scroll in a badly damaged area below emperor Jiaqing’s seal. Xuantong was the motto used in the reign of the last emperor of China, Puyi 溥儀 (1906–1967) who was enthroned as a two-year-old child in 1908 and abdicated in 1912. The historic situation encapsulated in this scroll was certainly something Puyi could personally relate to.

In the 1930s the artefacts from the former imperial collection were packed into wooden crates and transported far away from Beijing due to fears of an imminent attack by Japanese troops. After the war against Japan and the subsequent civil war between nationalists and communists – which ended in the communist victory – the nationalists took a large part of the imperial art collection with them to Taiwan. Today, Picture of Jingxi is part of the National Palace Museum collection in Taipei. In 2012, the scroll was declared an Important Cultural Relic. Over time, this painting, a personal artefact encapsulating notions of loss, trauma and the abhorrence of war, was collected by emperors, and is now considered a work of art, displayed in this world-famous museum.

References

- Bian Yongyu 卞永譽 (2012), Shigutang shuhua huikao 式古堂書畫匯考, original, s.l., 1682, facsimile Hangzhou: Zhejiang renmin meishu chubanshe, 2021 [1st edn: 1921].

- Bloom, Phillip (2008), ‘Mapping Violence in the Late-Yuan Jiangnan Landscape: Chen Ruyan’s 陳汝言Jingxi Tu 荊溪圖 of 1359’, unpublished manuscript.

- Brown, Claudia (1985), Ch’en Ju-yen and Late Yuan Painting in Suchou, PhD thesis, University of Kansas.

- Clapp, Anne de Coursey (2012), Commemorative Landscape Painting in China (Tang Center Lecture Series), Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Wang Jie 王杰 et al. (eds) (1971), Shiqu baoji xubian 石渠寶笈續編, original, Beijing, 1793, facsimile Taipei: National Palace Museum.

- Zhang Guangbin 張光賓 (1983), ‘Kan hua shuo gu - cong Chen Ruyan Jingxi tu shuo qi’ 看畫說古-從陳汝言「荊溪圖」說起, Gugong wenwu yuekan 故宮文物月刊, 1:71–73.

- Zhu Cunli 朱存理 (1991), Shanhu munan 珊瑚木難, vol. 2, original, s.l., late fifteenth century, facsimile Shanghai: Guji chubanshe [1st edn: 1970].

Description

Chen Ruyan, Picture of Jingxi

National Palace Museum in Taipei, Taiwan

Material: hanging scroll, ink on silk

Size: 129 × 52.7 cm

Provenance: Suzhou, fourteenth century

Copyright Notice

Copyright for all photographs: National Palace Museum, Taipei

Reference note

Uta Lauer, All that remains – A Painting with Inscriptions In: Wiebke Beyer, Karin Becker (eds): Artefact of the Month No 18, CSMC, Hamburg, https://www.csmc.uni-hamburg.de/publications/aom/018-en.html