A Clash of Traditions? – Codex runicus

Britta Olrik Frederiksen

In October 1728 a fire broke out in Copenhagen, destroying much of the city, including the University Library. At the last moment Professor Árni Magnússon succeeded in having his invaluable personal manuscript collection brought to safety. Among the manuscripts was one that did not originally belong in the collection and to this day it is not clear how it got there. The manuscript itself is just as mysterious, for it has the form of a medieval codex, but the text is written entirely in runes. Why were such different writing traditions combined in one written artefact?

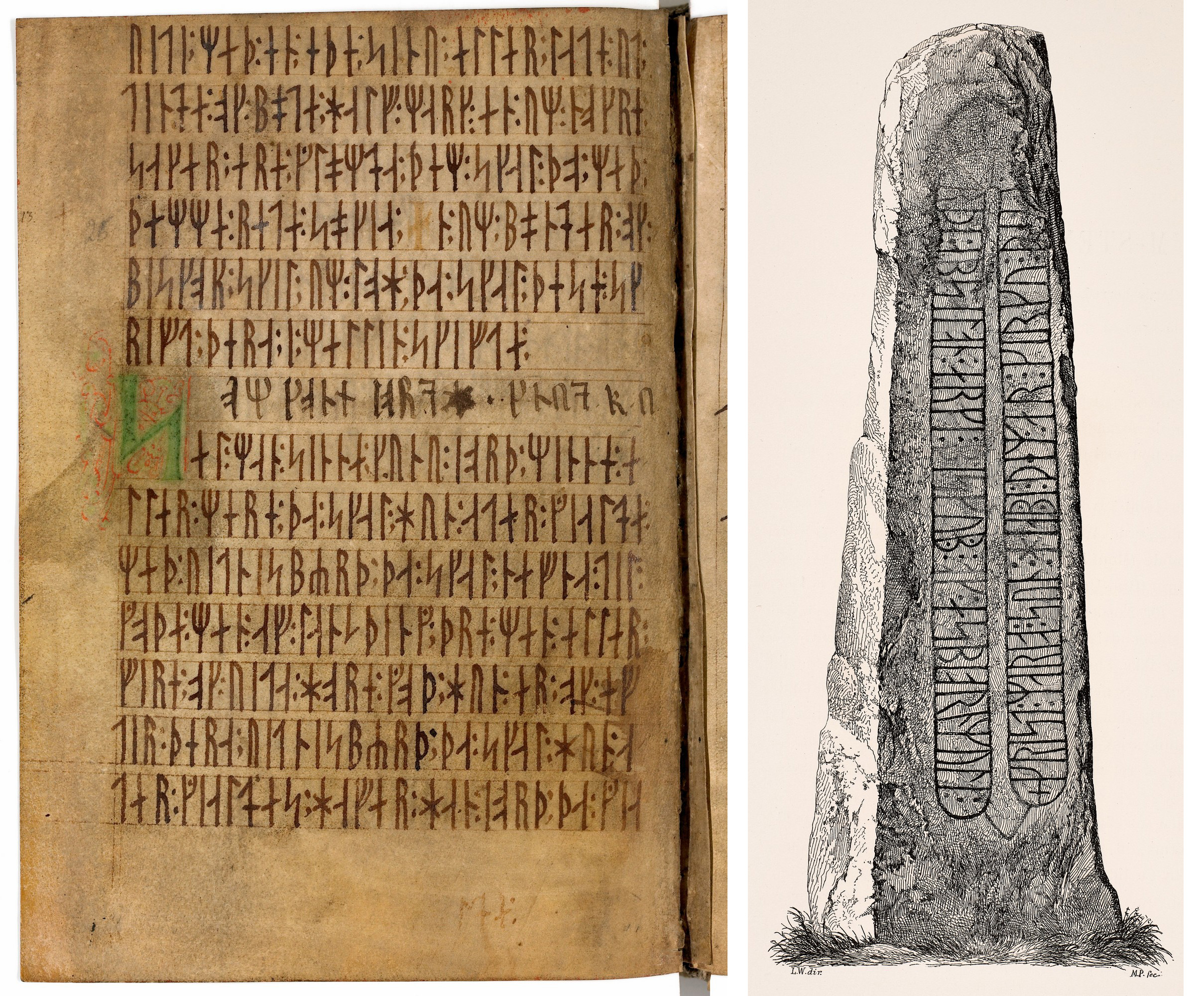

As far as is known, Codex runicus is the only extant codex from the Middle Ages written in runes and thus, apparently, representing a unique clash between different scribal traditions. A codex consists of sheets of parchment or paper folded over one another into gatherings and then sewn together into a book-block. This format spread throughout Europe along with the Latin script and Christianity and probably reached Scandinavia in the eleventh century. The runes, on the other hand, are descendants of an ancient Germanic scribal tradition that can be traced back to the second century. Runes are normally found in inscriptions on bone, metal, stone, or wood and, as epigraphic writing, they survived in Scandinavia long after the arrival of the codex and the Latin alphabet.

Codex runicus bears the shelf-mark AM 28 8vo and is housed in the Arnamagnæan Collection at the University of Copenhagen. It is a parchment manuscript measuring 17.7 × 12.5 cm, and the surviving (1+) 100 leaves have a post-medieval parchment covering. The language is Danish at an early stage, i.e., before 1350, and the contents are, with only one exception (Runekrøniken, ‘the Runic Chronicle’), known from other sources.

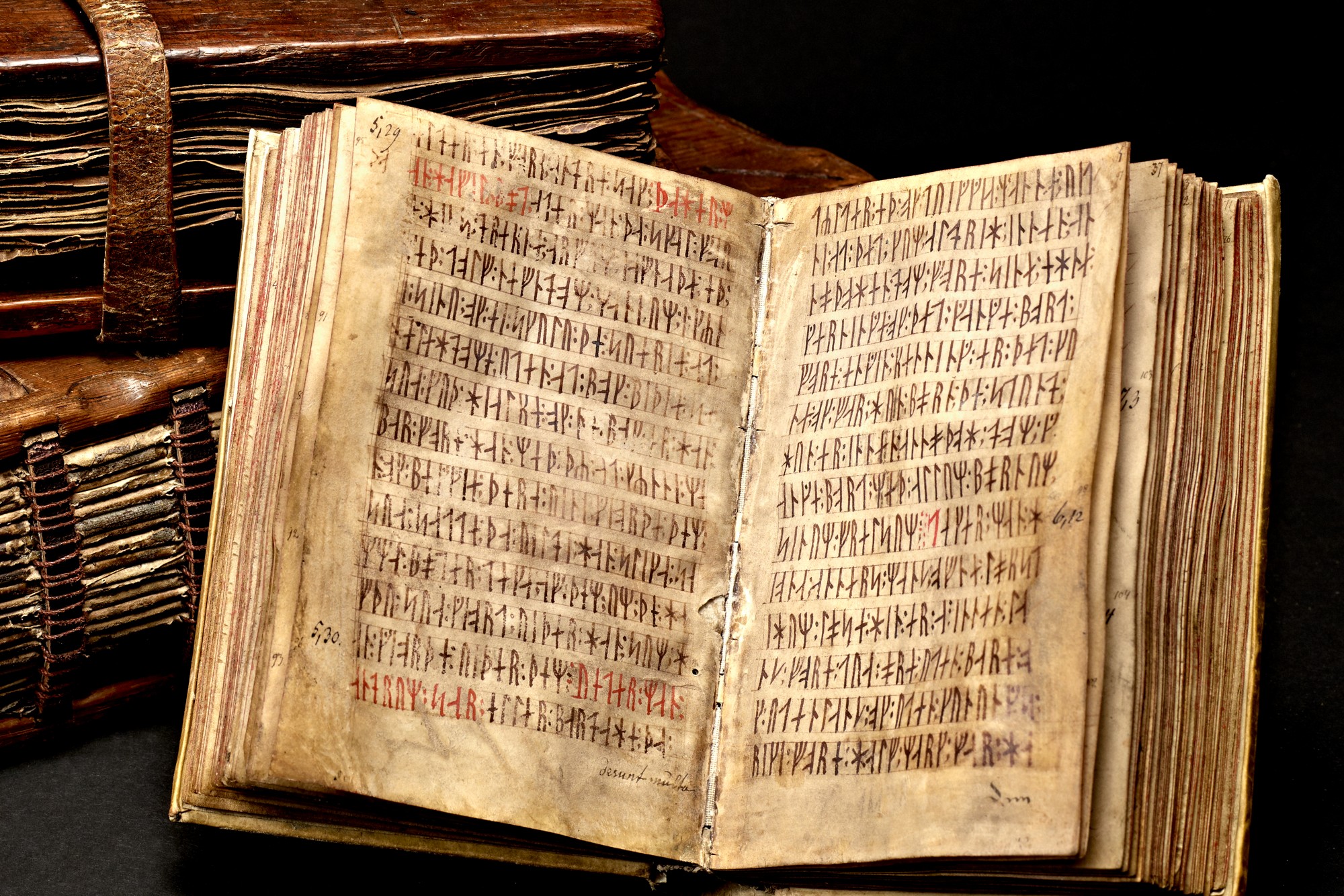

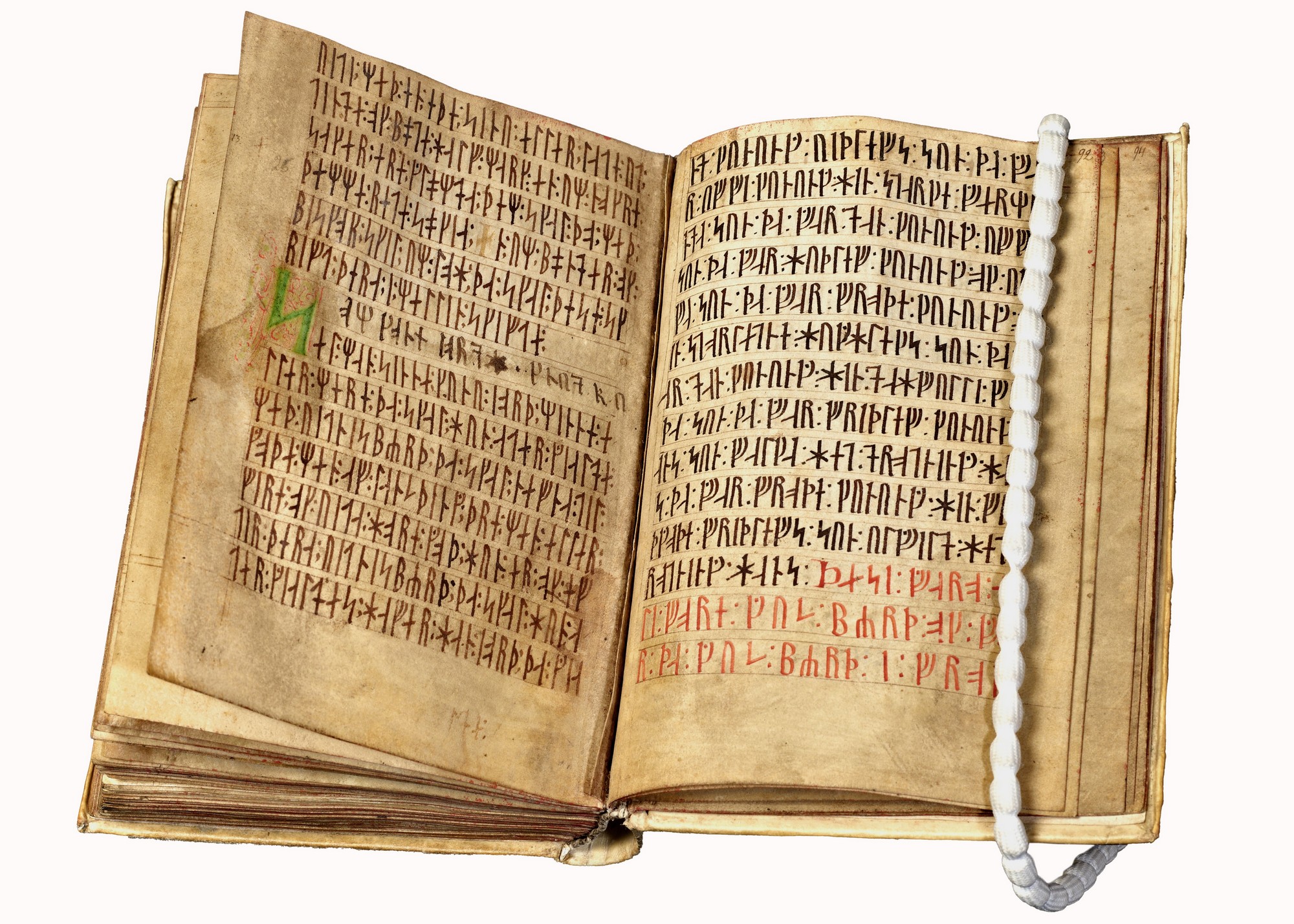

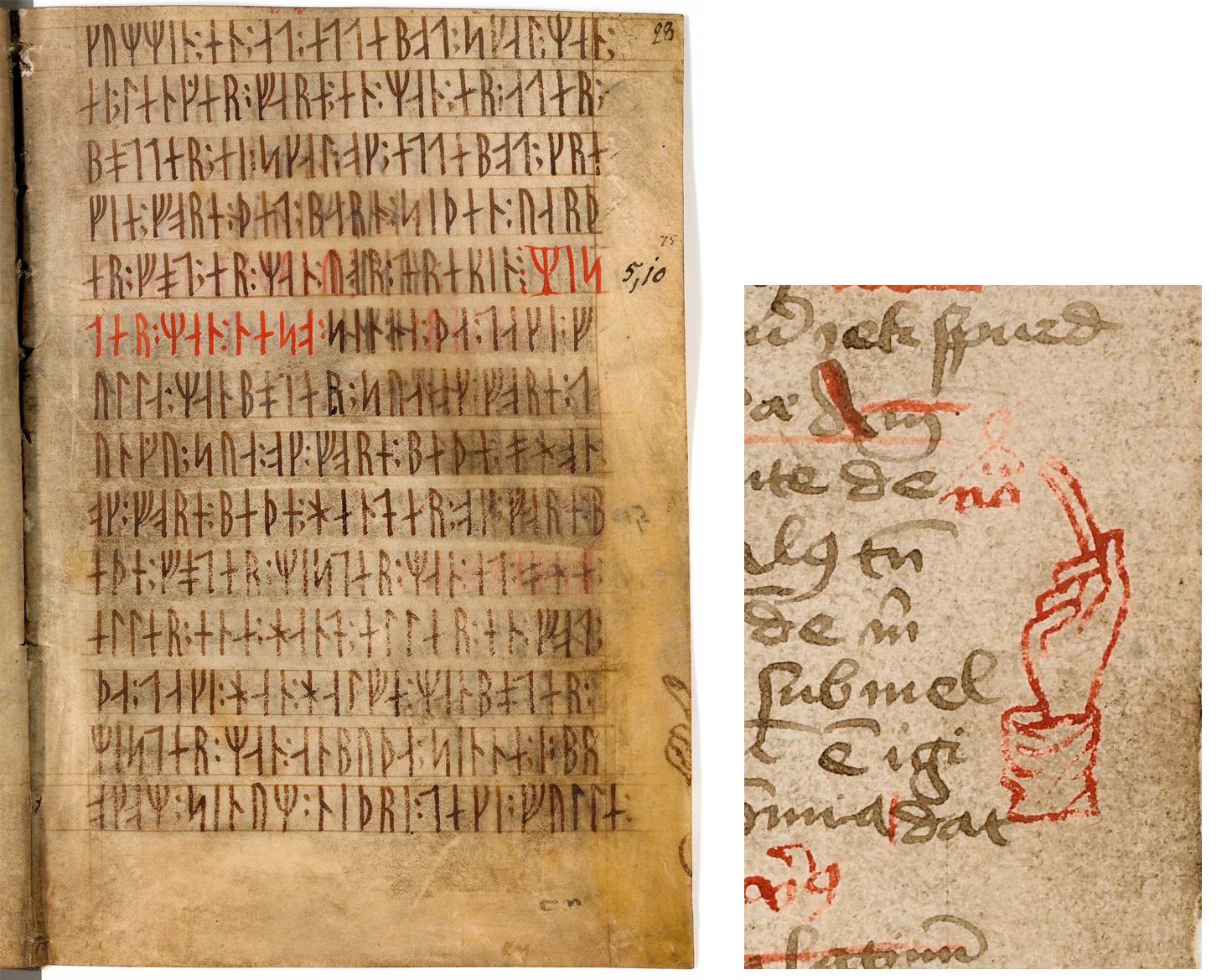

The main text is Skånske Lov (‘Scanian Law’), finalized at the beginning of the thirteenth century as the law for the provinces of Skåne, Halland and Blekinge on the Scandinavian peninsula; these provinces were then part of Denmark but came under the Swedish crown in 1658. Two supplements and the Skånske Kirkelov (‘Church Law’, an agreement reached in the 1170s between the Archbishop in Lund and the Scanians) follow the law proper. All the legal material (leaves 1–91) is written in the same neat hand (Fig. 2), except perhaps the first supplement (leaf 83), where the script has been overwritten, making it difficult to identify.

The last leaves (92–100), written in another and less regular, but not necessarily younger hand, contain short historical texts. The first is a laconic fragment of a Danish king list (leaf 92), followed by a slightly more informative king list (Runekrøniken, leaves 93–97r) which ends with Erik Menved (reigned 1286–1319). The final text purports to record a Danish-Swedish agreement from the eleventh century concerning the boundary between the two kingdoms (leaves 97r–100r). This text includes striking factual mistakes and has been interpreted as a fabrication from the thirteenth century with the aim of documenting an old Danish right to the frontier provinces of Halland and Blekinge, north and east of Skåne respectively. According to this text both lie on the Danish side.

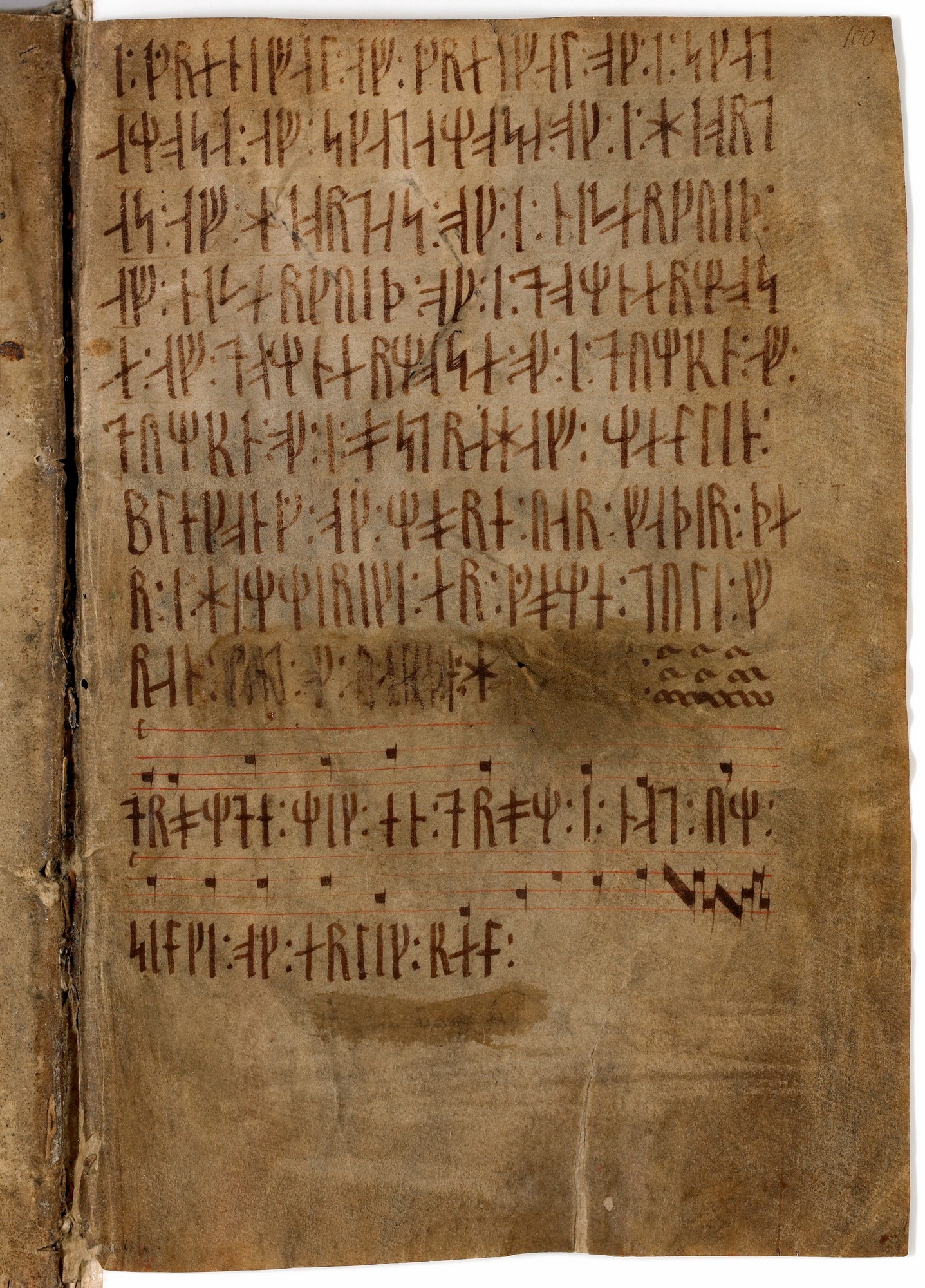

At the bottom of leaf 100r enough space remained to include a small verse with an accompanying melody, probably the oldest fragment of secular music preserved in Scandinavia (Fig. 3). The ballad-like verse runs in translation ‘Last night I had a dream of silk and glorious pæl [Modern Danish (antiquated) peld, a kind of expensive fabric]’. The verse is otherwise unknown.

The flyleaf at the front of the book contains exclusively post-medieval notes, mainly in Latin script. They indicate that Codex runicus passed through the hands of various Danish scholars, starting in the last third of the sixteenth century, and ended up – obviously by a mere stroke of good luck – in Professor Árni Magnússon’s (1663–1730) invaluable manuscript collection which he bequeathed to the University of Copenhagen.

The runes employed are, with small modifications, taken from the so-called ‘dotted’ runic alphabet. It was based on the 16-character Viking-Age runic alphabet with new symbols created partly by adding dots to existing rune forms. In this way, it was reorganized into an alphabet with symbols corresponding to just about all the letters of the Latin alphabet – not quite 30 – and was commonly used in medieval runic inscriptions (on gravestones, church furnishings etc.). In addition to the runes themselves, the manuscript’s use of two dots above each other to indicate word boundaries (Fig. 4) is undoubtedly a runic tradition. The fact that three or more dots in the law section can serve as punctuation is probably the invention of the skilled scribe – rather than additions by later readers. Furthermore, the layout of the pages is almost certainly inspired by the incised frames on rune stones since it has the characteristic framing rules rather than the single rules normally found in medieval manuscripts (Fig. 4). Throughout the manuscript, the ruling seems to have been done in a single phase which argues against an earlier theory that the two sections of the manuscript originally formed two separate manuscripts.

From the Latin scribal tradition derives the palmette-like design that decorates initials in two places in the legal section (Fig. 4) and the use of red or ochre or (once) blue ink for emphasis. In the legal section red and ochre often but not always indicate the beginning of a chapter – affecting the first few words or just the first letter. In the historical section red is used for the only surviving heading as well as in passages where the content seems to have been considered essential: firstly, the reference to the Birth of Christ in the first king list, and secondly, in the boundary-text, the account of the procedure for establishing the boundary and the places where the boundary stones were set up. Moreover, a well-known symbol from the Latin tradition, a manicula ‘little hand’, is glimpsed in the right margin of leaf 28r, or rather what the bookbinder´s knife has left of one (Fig. 5). The hand points to the text in the last three lines of the page and might have been added by the scribe, judging from the character of the ink. The reason for calling attention to these lines is obvious. The chapter is about fines for cutting off parts of a man’s body and just here full blood money is prescribed if a man loses ‘his tools in his trousers’. According to a contemporary Latin paraphrase of the law this humiliation was by many regarded as worse than death. The manicula in the margin of leaf 99r is probably post-medieval; the accompanying explanation in Latin – half cut-away – seems to indicate a crucial point in the boundary-text.

Codex runicus is difficult to date. The historical section could not have been written before 1319 since the Runekrøniken uses the past tense to inform us that Erik Menved’s queen was called Ingeborg, and she died in 1319. It is unlikely that the legal section is much older. A reliable counterpart written in runes might help in dating the manuscript but no such counterpart has been found. The existence of a single other Scandinavian runic manuscript whose linguistic form is comparable to that of Codex runicus and which is at least partly written in a hand similar to the second hand in Codex runicus is of little assistance, because this amulet-like duodecimo fragment can only be dated to the time after 1200, a date generally applicable to manuscripts written in Danish. The oldest marginal and interlinear additions written in Latin letters in Codex runicus have been dated to the fifteenth century, thus, the latest possible date of the manuscript must be c. 1500.

Even more uncertain is the manuscript’s place of origin. The contents and language point unequivocally to Eastern Danish provinces but any attempts to locate the place of origin more closely have been weakly substantiated. One possibility is the Cistercian monastery of Herrevad due to its possible relationship to the rune manuscript fragment whose text is attributed to a Cistercian. Another guess is the Augustinian monastery in Dalby, where objects have been found that suggest an interest in the runic culture.

There is no definite answer to the question as to why runes were used to write this manuscript. Although the evidence hitherto presented – pertaining mainly to presumed scribal errors – is not unambiguous, nevertheless, it seems most likely that the exemplar for Codex runicus, or the exemplar for the exemplar, was a manuscript written in the Latin alphabet. If this conclusion is correct, then the manuscript is a perfect example of deliberate antiquarianism. The motivation may have been cultural: a wish to revive the genuine Scandinavian script, but it may also have been political: a desire to show that an ancient writing tradition underlies this specific selection of texts linking Skåne, Halland and Blekinge to Denmark. Between c. 1330 and 1720, the three provinces were a bone of contention between Sweden and Denmark. In Codex runicus the law for these eastern provinces is accompanied both by the highlighted boundary agreement placing Skåne, Halland and Blekinge in Denmark and by the lists of kings of Denmark, including Svend Forkbeard(d. 1014) who is said to have been the Danish contracting party to the agreement.

Finally, the question remains as to whether we are considering a clash of traditions or a natural chronological sequence of traditions. Is it possible that Codex runicus is simply one of an earlier group of codices – written in runes – which preceded those in written Latin letters? This scenario seems most unlikely: The writing instrument used for parchment and paper, the so-called broad-stylus, worked very well for the flexible Latin letters, but the stiff shape of the runes simply did not go well with it.

Digitized manuscript

AM 28 8vo, Codex Runicus https://www.e-pages.dk/ku/579/ (accessed on 8 November 2021).

References

- Aakjær, Svend and Erik Kroman, assisted by Jørgen Olrik and Hans Ræder (eds) (1933): Skånske Lov. Anders Sunesens parafrase, Skånske kirkelov m.m. Danmarks gamle landskabslove med kirkelovene, vol. 1.2, Copenhagen: Gyldendal.

- Brøndum-Nielsen, Johs. (rev.) (1918), ‘Nils Hänninger, Fornskånsk ljudutveckling. En undersökning av cod. AM. 28, 8:o och cod. Holm. B 76, Lund (& Leipzig) 1917’, Nordisk Tidsskrift for Filologi, 4. series, 7: 38–43.

- Brøndum-Nielsen, Johs. (ed.) (1932), ʻLandegrænsen mellem Danmark og Sverige efter Codex Runicus af Skaanske Lov’, in Danske Sprogtekster til Universitetsbrug, vol. 1, 2nd edn, Copenhagen: J.H. Schultz, 13–14 [1st edn: 1925].

- Brøndum-Nielsen, Johs. and Aage Rohmann (eds) (1929), Mariaklagen efter et runeskrevet Haandskrift-Fragment i Stockholms Kgl. Bibliotek, Copenhagen: J.H. Schultz.

- Brøndum-Nielsen, Johs. and Svend Aakjær (eds) (1933), Skånske lov. Text I-III. Danmarks gamle landskabslove med kirkelovene, vol.1.1, Copenhagen: Gyldendal.

- Danielsen, Martin Sejer (2012), ʻInterpunktionen i runehåndskriftet AM 28 8vo af Skånske Lov’, Danske Studier, 2012: 150-161 [with an abstract in English].

- Danielsen, Martin Sejer (ed.), Skånske Lov (AM 28, 8vo) https://tekstnet.dk/skaanske-lov/metadata (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Drømte mig en drøm i nat (AM 28, 8vo; lemmatiseret) https://tekstnet.dk/droemte-mig-en-droem/metadata (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Imer, Lisbeth M., Foto Roberto Fortuna (2016), Danmarks runesten. En fortælling, Copenhagen: Nationalmuseet and Gyldendal.

- Lorenzen, M[arcus] (ed.) (1887–1913), Gammeldanske krøniker, Copenhagen: Samfund til udgivelse af gammel nordisk litteratur.

- Om konejord; Skånske Lov, tillæg III, 1 (AM 28, 8vo; fragment) https://tekstnet.dk/om-konejord/metadata (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Palm, Rune (2010), ʻRunorna under medeltid’, in Inger Larsson, Sven-Bertil Jansson and Barbro Söderberg (eds), Den medeltida skriftkulturen i Sverige. Genrer och texter, Stockholm: Sällskapet Runica et Mediævalia and Stockholms universitet, 26–52.

- Sawyer, Peter (1988), ʻ“Landamæri I”: The supposed Eleventh Century boundary treaty between Denmark and Sweden’, in Aage Andersen, Troels Dahlerup, Ulla Lund-Hansen, Jørgen Steen Jensen and Niels-Knud Liebgott (eds), Festskrift til Olaf Olsen på 60-års dagen den 7. juni 1988, Copenhagen: Det kongelige Nordiske Oldskriftselskab, 165–170.

- Skovgaard Boeck, Simon (ed.), Bodløst mål; Skånske Lov, tillæg I, 1 (AM 28, 8vo; lemmatiseret) https://tekstnet.dk/bodloest-maal/metadata (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Skovgaard Boeck, Simon (ed.), Kongetal (AM 28, 8vo, fragment) https://tekstnet.dk/kongetal/metadata (accessed on 17 November 2021).

- Skovgaard Boeck, Simon (ed.), Landegrænse mellem Danmark og Sverige (AM 28, 8vo) https://tekstnet.dk/landegraense/metadata (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Skovgaard Boeck, Simon (ed.), Runekrønike (AM 28, 8vo, fragment) https://tekstnet.dk/runekroenike/metadata (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Skovgaard Boeck, Simon (ed.), Skånske Kirkelov (AM 28, 8vo) https://tekstnet.dk/skaanske-kirkelov-am28/metadata (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Thorsen, P.G. (1877), Om Runernes Brug til Skrift udenfor det monumentale, Copenhagen: Gyldendal.

- Westlund, Börje (1994), ʻRunorna och den latinska skriften’, in Solbritt Benneth, Jonas Ferenius, Helmer Gustavson and Marit Åhlen (eds), Runmärkt. Från brev till klotter. Runorna under medeltiden, Borås: Carlssons, 119–126.

Description

Arnamagnæan Collection at the University of Copenhagen

Shelfmark: AM 28 8vo

Material: parchment, (1+) 100 leaves

Measurements: 17.7 × 12.5 cm

Provenance: the former Danish provinces (Skåne, Halland and Blekinge) on the Scandinavian peninsula

Date: first quarter of the fourteenth century (?)

Copyright Notice

Manuscripts, Copenhagen, Arnamagnæan Collection AM 28 8vo and AM 76 8vo: Photograph: Suzanne Reitz. Published with the permission of the Arnamagnæan Institute.

Reference note

Britta Olrik Frederiksen, A Clash of Traditions? – Codex runicus. In: Wiebke Beyer, Karin Becker (eds): Artefact of the Month No 16, CSMC, Hamburg, https://www.csmc.uni-hamburg.de/publications/aom/016-en.html