Berta and St Peter

Ordinary People under the Protection of St Peter’s Monastery

Till Hennings

Anyone who has seen medieval charters in a museum probably remembers them being as large as a poster, full of fancy and artistic writing, and adorned with many seals. That is how the great charters of the high Middle Ages looked – issued by emperors, popes, and powerful city states. How very different is the charter in the archive of Gent, shelf-mark K99, Nr. 174. This document is small and quite unexceptional, and yet it guarantees the legal status of a whole family for generations.

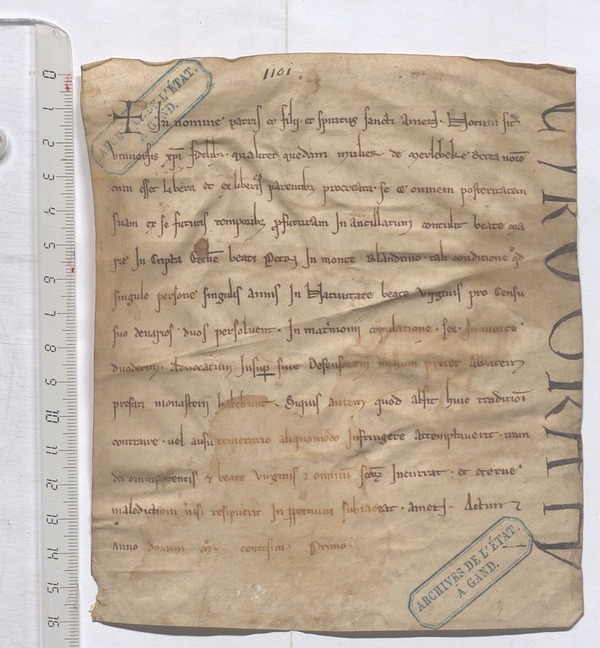

Even a passing glance at the charter shows that we are in a very different world – the world of ordinary people: the craftsman, the street vendor and the small shopkeeper, the fisherman and the day labourer. The parchment of the charter is hardly bigger than two postcards put together. The diplomatic minuscule in which the text is written is typical of the time, and, apart from the blessing cross at the beginning of the text (Fig. 1) and a very small number of ornamented letters, the scribe uses no decorative elements. There are no seals, not even signatures. The text is written in Latin, the official literary language of the time; ordinary people could not write, and certainly not write Latin; thus, the document was written by a monk in the chancellery of the monastery of St Peter’s. With this document, a woman named Berta accepts the protection of St Peter’s monastery in Gent.

The charter itself reveals the temporal setting in the final line where we read 'anno domini M[illesimo] centesimo primo’. Thus, we find ourselves in the year 1101 in medieval Gent, a prospering city in Flanders (now northern Belgium). At least three powerful figures dominate the region and time: the Duke of Flanders (and its noble vassals) and two monasteries, St Peter’s and St Bavo’s. The inhabitants of the city had little or no political power at this time, although, in due course, they would control the fortunes of rich trading cities such as Gent (or Bruges and Ypres).

St Peter’s monastery is one of the oldest monasteries in Flanders. It was founded in 630 by St Amandus, the apostle of the Belgians, and attained the height of its influence between the tenth and twelfth centuries. Many documents – including the one described here – have come down to us from that time. These documents were handwritten on parchment, and their purpose was to record and endorse legal agreements. Such testimonies included business transactions, e.g. a sale or an exchange, or private law about inheritance or dowry, but also political contracts concerning rights and privileges. For centuries, medieval monasteries collected such documents in order to prove the legitimacy of their many possessions; indeed, these were often disputed, by other monasteries, or by bishops, dukes, and kings. Thus, to a certain extent, the archive was worth more than all the golden chandeliers and silver gospels, for, in fact, the archive made such worldly wealth possible. The archive of St Peter’s has preserved a great number of documents concerning ordinary people like Berta. This is surprising because, normally, the contents of such documents were very different; for the most part, they involved land ownership but also e.g. tribute or customs duties. In economic terms, such contracts were of enormous importance since the tribute made by peasants to the landowners (the monastery) was made in kind. The peasants were bound to their landowners by many other obligations and duties – a system of bondage that nowadays is often referred to as serfdom.

Gradually, over the course of the eleventh century, a new kind of dependence appeared alongside serfdom. The so-called Zensualität was an ecclesiastical tribute, to be paid by the individual, and represented a medieval form of tenancy. Berta, the woman named in the charter under discussion is such a woman, an ecclesiastical tributary. Tributaries stood under the protection of the monastery, or, as it was expressed at the time, under the protection of the patron of the monastery, St Peter. They were required to pay the monastery an annual payment (German: Kopfzins, -zins from Latin census) as well as marriage and death duties. The annual payment was to be made in cash; how they earned this money was left up to them. Compared to the serfs the tributaries had many advantages: they could choose their own profession, they enjoyed freedom of movement, and, most importantly, they were legally protected by the monastery in any confrontation with those in power. These privileges gave the tributaries the possibility of settling in the cities, still under the protection of the monastery, and able to pursue a craft or trade. In this way, they became an early prototype of the burghers of the Middle Ages.

The status of tributary was inherited by the children from the mother. Matrilineal inheritance ensured that the correct legal status of the parents was passed on, for paternity could be wrongly attributed. In the present case, this means that, if the mother was a tributary, the children – sons or daughters – were subject to paying tax. The children of the daughters – the maternal grandchildren – were automatically tributaries, inheriting the status of the mother. Whether the children of her sons – the paternal grandchildren – were subject to tax depended on their mother – who married into the family.

The status of tributary – and the possibility of inheriting the status – was not a contract of employment between the monastery and the copyholders. Rather, it was a contract of dependence, and theoretically indissoluble.

Our Berta came from Merelbeke, not far from Gent and freely entered the status of tributary. Her name can be seen at the end of the second line of the document (Fig. 1). The text of the document emphasises the fact that she is free-born and that her parents were free-born. Furthermore, the document stipulates that not only Berta, but also all her descendants (omnem posteritatem suam) are bound to this status – as was customary in charters establishing the status of copyholder. The tax which she (and all her descendants) had to pay was two dinars per year; additionally, they had to pay a marriage and death duty (six and twelve dinars). The value of a denarius (Latin; a ‘silver penny’) at any particular time or place is difficult to establish; we lack data on the general economic situation, on deflation and inflation, as well as information about wages and prices. What is known about such facts from the eighth to the thirteenth century allows us to postulate that the daily remuneration for a skilled worker in the town or city was between two and four denarii. Thus, even if we assume that prices were relatively high, the tax was not oppressive.

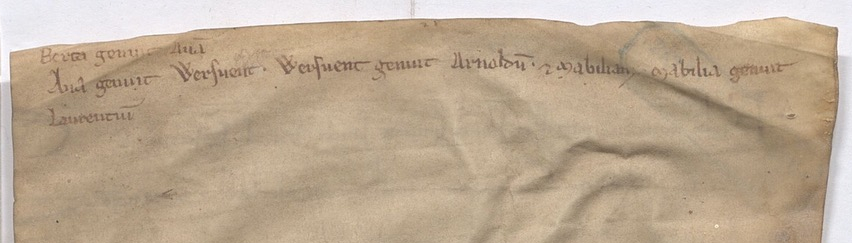

On the reverse side of the document is a further sentence (in Latin): ‘Berta begot Ava, Ava begot Wersvent, Wersvent begot Arnold and Mabilia, Mabilia begot Lorenz’ (Fig. 2). Here, five generations of a family were listed by a scribe at least 60 years after the original document had been written. This genealogy of ordinary people – not nobles – documented the family’s status as tributaries. As mentioned above, this status was inherited through the mother and only the maternal line is listed here. The depth of the ancestry – five generations – is quite remarkable: in the present-day, few people would know the name of their great-great grandmother on the maternal side without having to research it.

The reason for listing the genealogy in this way can only be guessed at. One possible explanation is that, by acknowledging the status of Mabilia and Lorenz, the monastery was demanding that they repay their unpaid taxes; however, such an option belongs more properly in the stereotype of ‘powerful church against powerless serf’. It is more likely that Berta’s descendants needed the document to prove their tributary status, in order to avoid the danger of their being treated as mere vassals or serfs – by a worldly power such as the city administrator or the local earl. The monastery had a duty to protect its tributaries against such risks; this included providing proof that Berta’s descendants genuinely belonged to the familia of the monastery. It should not be forgotten that the status of tributary was not a tedious duty, it was – in contrast to the available alternatives – a highly valued privilege. An earlier charter in Gent (RAG 107, 1034‑1058) tells us the story of such a legal dispute. In this document some members of the nobility claim that the descendants of a certain Avacyn are their vassals. These descendants turned to the monastery for support and, with the help of a witness, proved their status as tributary of St Peter’s. It was always possible that Berta and her descendants might face such a threat.

A further detail on our charter offers additional insight into the diplomatic practices of the times. Along the right-hand edge of the paper a rather strange script can be seen in which only half the letters are visible (Fig. 1). From other documents we know that the word ‘C[h]yrografu[m]’ was written there. The word ‘Chirographum’ simply means ‘hand-writing’ and – from its origins in the Roman tradition of writing such charters – this custom took a somewhat circuitous route into the chancelleries of the early and late Middle Ages. Such chirographs were an early form of protection against fake documents or forgeries. The text would be written twice on a parchment and the latter then cut in half along the chirograph, hence, the Latin name for such charters: charta partita, divided document. Each party retained one half and, in the case of a dispute, the authenticity of the document could be proved by placing the two halves together.

The half of the charter that was given to Berta can no longer be found. Nevertheless, the note on the verso of the document from St Peter’s clearly records the fortunes of Berta’s family over five generations, and was perhaps valid for further generations. At the same time, the document offers a fascinating insight into Berta’s world and that of her descendants, and thus into the world of ordinary people in Gent at the beginning of the high Middle Ages. A powerful monastery guaranteed the legal rights of citizens and laid the foundations on which the wealth of the great trading city of Gent was to flourish. The centuries-old writing traditions of the monastery affected the ordinary people: they had to prove their ancestry, they had to accept and safeguard their documents, and present them if required. It did not take long before they themselves took up the pen, fostering the writing culture which emerged in the trading centres of Europe in the high Middle Ages.

References

- Berings, Geert and Charles van Simaey (1988), 'L’Abbaye Saint Pierre de Gand', Monasticon Belge, 7/1, 69–154.

- Boeren, Petrus Cornelis (1936), Étude sur les tributaires d’église dans le comté de Flandre du IXe au XIVe siècle, Nijmegen: Instituut voor middeleeuwsche geschiedenis der Keizer Karel Universiteit te Nijmegen.

- Gysseling, Maurits and Anton Carl Frederik Koch (1950), Diplomata Belgica ante annum millesimum centesimum scripta, Brüssel: Belgisch Inter-universitair Centrum voor neerlandistiek.

- Nélis, Hubert (1923), ‘La rénovation des titres d’asservissement en Belgique au XIIe siècle’, Annales de la Société d’Emulation de Bruges, 66, 173–214.

Description

State Archives of Gent (Rijksarchief te Gent)

Shelfmark: K99, Nr. 174

Date: 1101

Material: parchment

Size: 16 × 14,5 cm

Copyright notice

Copyright for all images: State Archives of Gent (Rijksarchief te Gent)

Reference note

Till Hennings, Berta and St Peter: Ordinary People Under the Protection of St Peter’s Monastery. In: Wiebke Beyer, Karin Becker (eds): Artefact of the Month No 14, CSMC, Hamburg, https://www.csmc.uni-hamburg.de/publications/aom/014-en.html