‘God will make them rich’

… unless her father steals the marriage gift!

Claudia Colini and Daisy Livingston

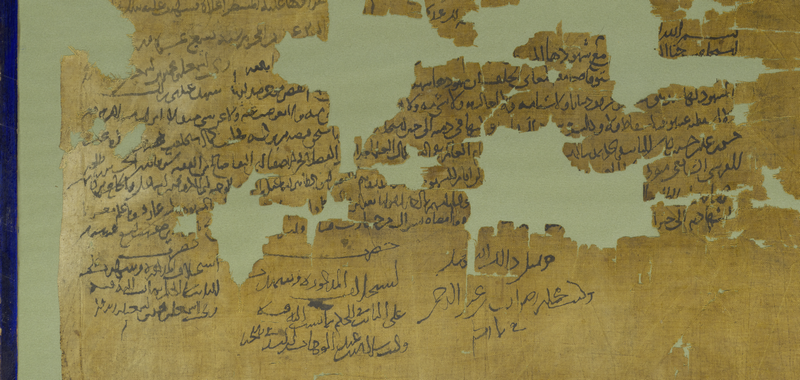

On 4 December 1207, a scribe in a provincial city in Egypt drew up a document recording the financial arrangements of a marriage. Following the legal rules and regulations of the time, he produced a lengthy Arabic text, and the agreement was accepted by witnesses. The couple were now husband and wife. Over the next fifteen years, however, the manuscript gained further texts, vestiges of a peculiar story of an injustice perpetrated by a father against his daughter.

The newlyweds were a merchant called ʿĪsā and his bride-to-be Khibāʾ. They lived in Bahnasa, the provincial capital of an administrative district of the same name, situated on the desert fringe of Egypt’s Nile valley, around two hundred kilometres south of the capital of Cairo. At the time, Egypt was under the control of the Ayyubid sultans, a dynasty of Kurdish rulers who had taken control of the country when Saladin stepped up from his role as vizier to the Fatimid caliphs and took on the mantle of ruler.

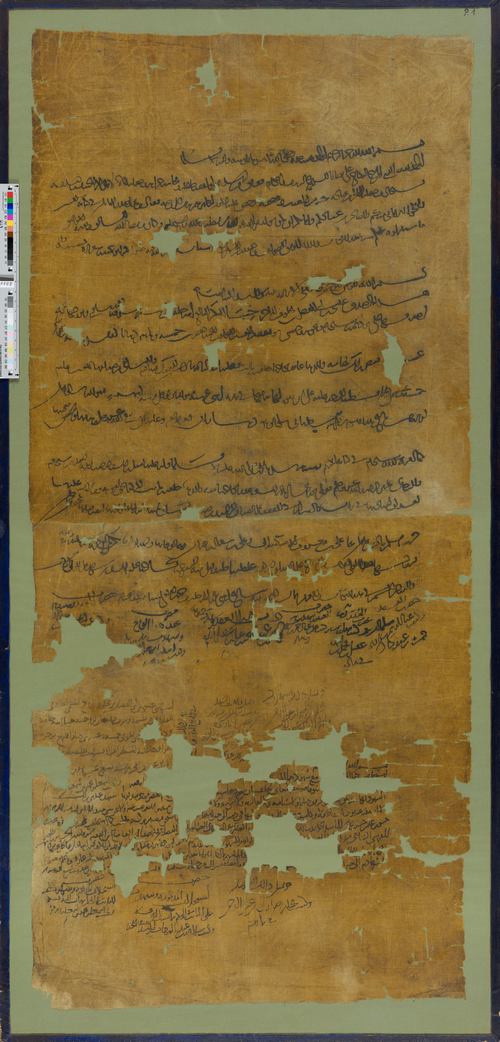

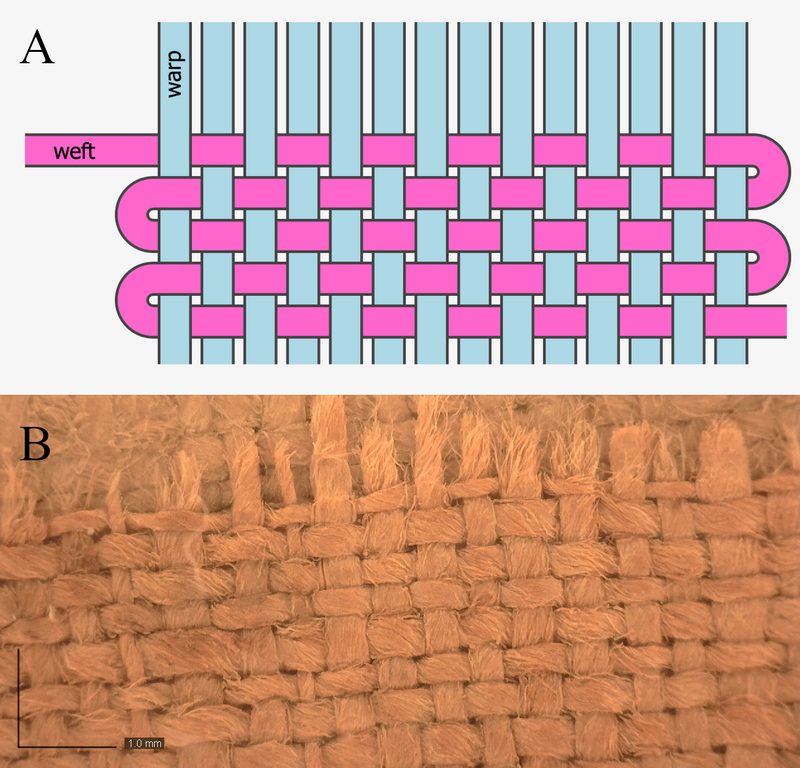

The marriage record, which is now housed in the Hamburg State and University Library, was written on two similar pieces of light-yellow linen, both of analogous dimensions and glued together to form a larger piece of 101,3 × 45,4 cm (Fig. 1). The textile is woven in a common plain weave: the weft thread goes over a single warp thread and down the following one, while the next weft thread does the exact opposite (Fig. 2). As the threads cross at right angles, they form a chessboard pattern. The linen is not high quality, as both threads have an irregular diameter. The yellow colour might be the result of a dye or of the degradation process of a white cloth. The lower part of the document has several holes, probably caused by the environment in which it was preserved, as such documents were often discovered in archaeological excavations.

Linen was a fairly unusual support for legal documents, but it had some precedent for marriage records and was perhaps selected to give these artefacts a special status and durability, as they sat right at the core of a family’s existence. For this couple the choice was especially pertinent since the bride came from a family of cloth merchants, and the groom may also have been involved in this trade. For them a piece of cloth would have been easy to acquire in the form of leftovers and not too costly compared to expensive parchment or high-quality paper.

The contents of the manuscript deal with the financial settlements involved in the contracting of a marriage: the husband’s payment of a marriage gift to his wife. These procedures conventionally involved several stages, with one sum being paid upfront and another deferred. Reflecting this multi-stage procedure, it is common to see marriage records containing various texts from different dates, with texts added to older records to keep them up-to-date. In our manuscript we can see several blocks of text, visibly distinct from one another by the shades of ink and handwriting. These were written on three occasions covering a period of fifteen years, and include the handwriting of at least fourteen individuals.

The first, and longest, text (text 1; Fig. 3) covers almost two-thirds of the surface and outlines the details of the settlement. After a four-line preamble extolling the benefits of marriage and citing the Qur’an, we learn that Khibāʾ was owed 35 gold dinars as a marriage gift. 10 dinars was to be paid upfront, with the remaining 25 dinars to be paid in yearly instalments over the next twelve years and six months. 35 dinars is a reasonably large sum for people outside the period’s elite and suggests that the couple came from relatively affluent mercantile families.

The scribe who wrote text 1 has an elegant though cursive hand, typical for legal documents of the period. He used a decorative layout: the first five lines include the opening blessings and Quranic preamble, after which the lines are grouped into threes to give the text a repetitive visual pattern. Such techniques are common in marriage records and helped convey their symbolic status. Following the text are statements of six witnesses, written in columns. Witnesses ordinarily wrote their own statements but here one had his son write for him, presumably as he could not write. As legal affairs, marriage transactions required these witness testimonies to ensure their validity. Witnesses were particularly important in the Islamic judicial system, since without them a document would not be considered an authoritative record.

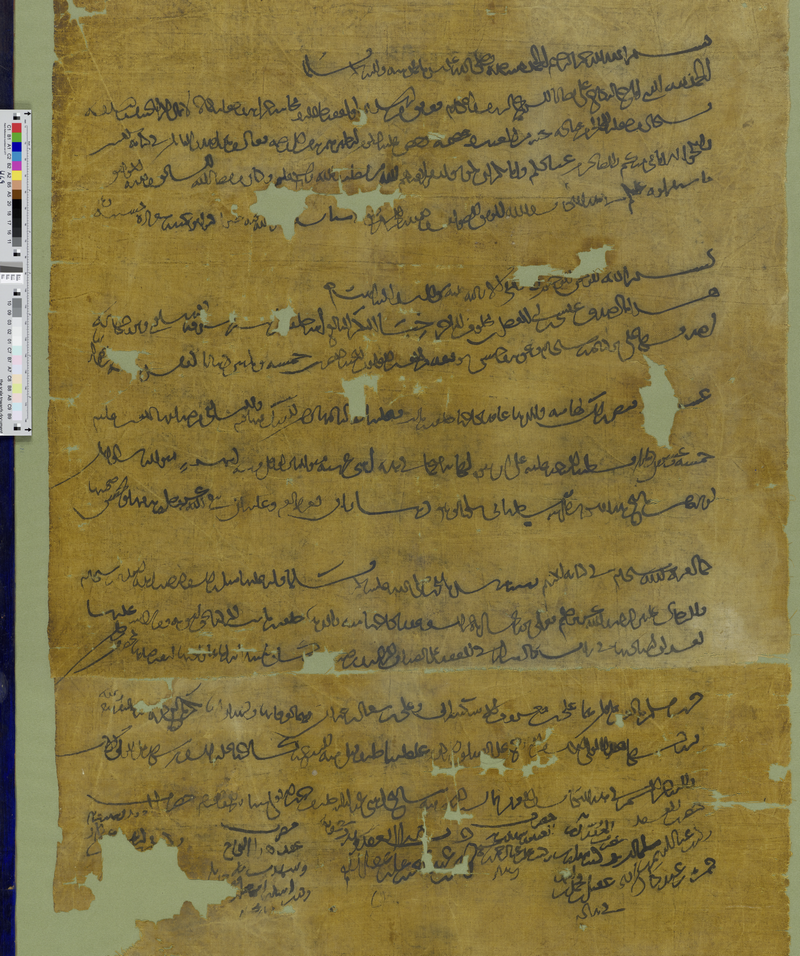

The second text (text 2; Fig. 4), added 13 years later on 20 March 1220, shows that the payment of the marriage gift initially proceeded according to plan. It explains that ʿĪsā had been cleared of his debt, having paid the 25 dinars to his father-in-law Khalīfa. Witnesses testified to this too. The scribe of text 2 wrote in fainter ink beneath text 1, starting around two-thirds of the way across the page. This positioning was not unusual in these kinds of updates to older records, presumably because scribes acknowledged that the added texts were subsidiary notices and did not demand the prominence of the main text.

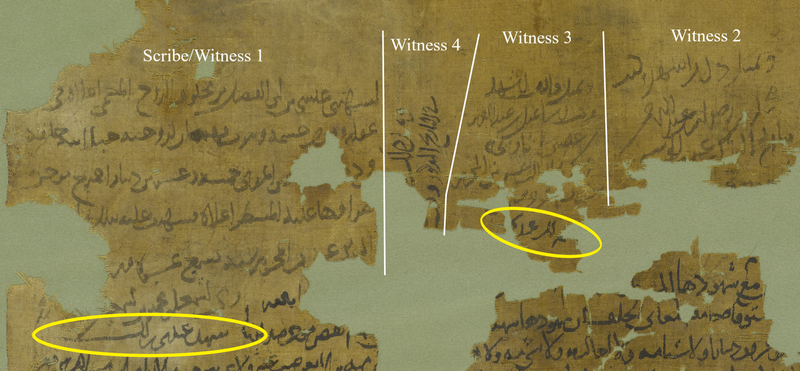

The layout of the witness statements supporting text 2 offer a puzzle of interpretation. They do not follow the usual pattern of appearing below the text in columns, but appear instead to the right of the text, one even written perpendicular to the other writing on the page with a darker ink (witness 4). It is tempting to imagine that these statements were added later, after the final text had been written, meaning that there was no space for them below text 2. They do, though, contain the date of text 2, so unless they were backdated to make it look like they had been added earlier, this seems unlikely. Either way, at least two of the witnesses passed assessment by a judge, who wrote his verdict on their reliability beneath their statements (Fig. 5). This is part of a legal procedure to ensure the validity of transactions. The intricacy of the layout show that this manuscript was shaped both by institutionalised legal procedures and practical concerns such as the available space on the page.

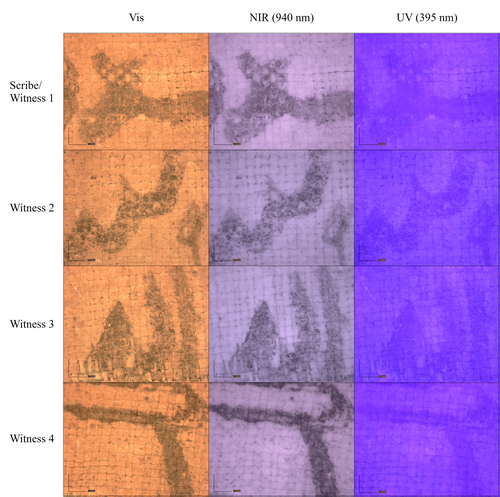

Though the content of the manuscript gives us a picture of how and when scribes added to its text, ink analysis can give us more detailed insight into the process of its production. By identifying the inks, we can learn whether all the witnesses signed on the same or different occasions, whether they shared writing materials, or used their own inks. Various kinds of inks were used in Egypt during this period: carbon, plant, iron-gall, and mixed inks. A first screening to classify the ink types was performed with a handheld microscope operating in visible light and in two specific wavelengths in near infrared (NIR) and ultraviolet (UV) light. We have observed that all the inks used in this manuscript are carbon-based (Fig. 6). This suggests that on each occasion only one ink was used, with the exception of text 2 where the ink used by witness 4 is visibly different. This might be an indication that he, at least, added his statement later, squeezing it in the empty space between the body of text 2 and the statement of witness 3, although the formula he used claims that it was still written on the same day. To confirm these hypotheses, we are currently applying additional techniques, used to identify mixed inks and to differentiate inks based on their impurities.

As for the content of text 2, there was nothing unusual about a woman being represented by her father. In fact, text 1 already explained that Khalīfa was acting in this capacity and was legally obliged to deliver the money to his daughter. What is surprising, however, is what we learn from the final text (text 3; Fig. 7). It reveals that two years later, on 29 March 1222, Khalīfa had still not handed over the money. This text, partially missing due to the holes in the cloth, reports that Khibāʾ swore an oath before a judge, complaining that she had not received the money. This kind of oath is not a procedure commonly attested in legal documents and was probably necessary because there was no other way of obtaining evidence that the money had not been paid.

Unfortunately, the story of this manuscript ends with text 3, so we do not know if Khibāʾ ever received her money. No final receipt appears to testify that the sum was handed over. Even without a satisfying ending, though, this manuscript offers us a fascinating glimpse into life, craft, and legal practice in a thirteenth-century provincial Egyptian city.

References

- Cohen, Zina (2021), Composition analysis of writing materials in Genizah Documents, Leiden/Boston: Brill.

- Dietrich, Albert (1952), ‘Eine arabische Eheurkunde aus der Aiyūbidenzeit’, in J.W. Fück (ed.), Documenta Islamica inedita, Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 121–154.

- Krakowski, Eve (2017), Coming of Age in Medieval Egypt: Female Adolescence, Jewish Law, and Ordinary Culture, Princeton: University Press.

- Mouton, Jean-Michel, Dominique Sourdel and Janine Sourdel Thomine (2013), Mariage et séparation à Damas au moyen âge. Un corpus de 62 documents juridiques inédits entre 337/948 et 698/1299, Paris: l’académie des inscriptions de belles-lettres.

- Rabin, Ira, Roman Schütz, Anka Kohl, Timo Wolff, Roald Tagle, Simone Pentzien, Oliver Hahn and Stephen Emmel (2012), ‘Identification and classification of historical writing inks in spectroscopy: a methodological overview’, Comparative Oriental Manuscript Studies Newsletter 3, 26–30.

- Rapoport, Yossef (2005), Marriage, Money and Divorce in Medieval Islamic Society, Cambridge: University Press.

Description

Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Carl von Ossietzky, Hamburg

Shelfmark: P.Hamb.Arab.1 (PURL: https://resolver.sub.uni-hamburg.de/kitodo/HANSh4116)

Material: two pieces of light yellow linen glued together, black carbon-based inks

Dimensions: 101.3 × 45.4 cm (two pieces of c. 50–51 × 45.5 cm)

Provenance: 604–619 AH / 1204–1222 CE, Bahnasa, Egypt

Ink analysis carried out by Claudia Colini, Olivier Bonnerot, Kyle Ann Huskin, Ivan Shevchuk.

Copyright notice

Fig. 1,3,4,7: Hamburg State and University Library (Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Hamburg Carl von Ossietzky), Germany

Fig. 2a: Lauren Nishizaki

Fig. 2b, 6: Claudia Colini

Fig. 5: Daisy Livingston

Reference note

Claudia Colini and Daisy Livingston, ‘God will make them rich’ … unless her father steals the marriage gift! In: Wiebke Beyer, Karin Becker (eds): Artefact of the Month No 13, CSMC, Hamburg, https://www.csmc.uni-hamburg.de/publications/aom/013-en.html