A Coffin, a Doll, and a Curse

An Ancient Artefact from an Athenian Cemetery

Sara Chiarini

In the middle of a night around 2400 years ago, an unknown Athenian sneaked into a cemetery carrying some very odd objects: a small lead coffin with a crooked doll inside it, both bearing inscriptions. He or she headed to a grave, furtively opened its roof and laid those objects as close as possible to the buried corpse while whispering some forbidden formulas. For more than two thousand years, the grave kept its secret, concealing the artefacts until they were discovered by archaeologists in the twentieth century. What kind of secret ritual had been performed?

Plato’s words reveal a side of ancient Greek civilisation that was long kept hidden by scholarship, strongly influenced as it was by the ideal of a knowledgeable and illuminated society. However, the ancient belief in the ubiquitous influence of divine forces can be seen as the source of private cursing practices. These rituals included activities such as the deposition of the inscribed curse, usually on a lead sheet, in a secret place (mostly a grave); here, contact with the powers of the underworld – where the addressees and executors of the curse resided – was believed to be the closest.

Curses in Greek and Latin, but also in other languages of the ancient world such as Aramaic, Celtic, Coptic, Phoenician and Oscan, are attested all over the ancient world and throughout almost all periods of antiquity. The case presented here is an excellent example of such an epigraphic curse, and shows the close semantic and functional relationship between the artefact and the written text. These two elements not only complement each other, they are mutually dependent.

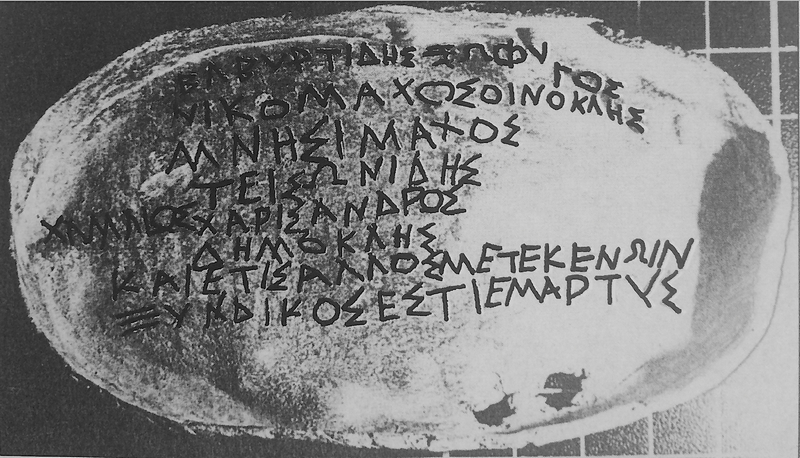

The object discussed here consists of an oval miniature coffin made of lead, and consisting in two parts, a container and a lid; enclosed therein was a male figurine also fashioned in lead (Fig. 1). It is dated around 400 BCE and was found in the grave of a male adult in one of the main cemeteries of ancient Athens, the so-called Ceramicus. The miniature coffin measures roughly 11 × 6 cm and is now preserved in the local museum.

The archaeological circumstances of the discovery are unclear: at the time of the excavations in 1940, the grave was still closed but the doll, the lid and the bottom of the miniature sarcophagus were found in three different places, the container being found outside of the grave. Moreover, inside the grave the bones of the skeleton were somewhat disordered. How could this disorder have occurred if the tomb was not open?

In the first publication on the find it was suggested that someone had known about the curse entrusted to the spirit of the dead person lying in the grave – such spirits were believed to be able to carry messages from the world of the living to the gods of the underworld – and wanted to cancel it by ritually mutilating the corpse. They would thus have opened the grave, performed their ‘anti-curse’ ritual and then carefully rebuilt the roof. Despite the fascination of such an interpretation, the events leading up to these puzzling circumstances were probably much more ordinary and, perhaps, accidental. One may start by posing the question as to why they did not destroy the cursing material.

More recently it was suggested that the original grave had not been sufficiently secured and that an animal managed to dig out the corpse and disfigure it. Following such an accident, one of the deceased’s relatives visiting the tomb would thus have re-built the grave with a more stable roof. Furthermore, since the cursing objects were neither removed nor destroyed, it is legitimate to regard that very relative as the author of the curse.

The question of why the author of the curse failed to put the pieces of the ritual artefact together again is open to a simple explanation: the reconstruction of the tomb must have taken place in the daytime, and perhaps under the supervision of a cemetery watchman. Our curser would thus have been under pressure: he or she did not want to be caught handling forbidden ritual objects and, perhaps, just managed to make sure that all the pieces were in the grave before it was closed. He or she might even have managed to place at least the doll where it was supposed to be: it was found just above the pelvic bones of the skeleton, i.e., right at the centre of the corpse.

Let us now have a closer look at the find: the inner side of the lid was engraved with a list of nine male personal names, followed by the closing sentence: ‘and anyone else who is an advocate or witness’. One of the listed names, Mnesimachos, was also carved along the right side of the lead figurine. Moreover, four names were added to the original list (shortly) afterwards; this assumption is corroborated by the fact that they were placed either above or outside the margins of the column containing the original list (Fig. 2). Since the terms advocate (σύνδικος) and witness (μάρτυς) are found in the inscription, the cursed people must have been involved in a trial. However, it is unlikely that they were all either prosecutors or defendants, since trials in ancient Greece were usually one-to-one disputes. Thus, all but one of the cursed people must have supported one of the parties to the case, either as advocates or as witnesses; this includes both those who were named and those who remained unnamed, i.e. those included in the curse by the closing sentence ‘anyone else who is an advocate or witness’. As was usual in curse inscriptions related to judicial matters, all the members of one party – and not just the main opponent – had to be affected by the curse, in order to make sure that none of the members of that party could persuade the judges.

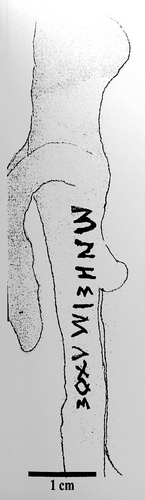

Yet, who was the actual enemy of the curser and thereby the main target of the ritual? The answer is found on the lead doll, carrying one of the names also included in the list: Mnesimachos must have been the main opponent of the curser, and the person who should suffer the greatest harm from the curse (Fig. 3). This idea is supported by the fact that his name is first in the original list of names – prior to the addition of the four other names.

Finally, what kind of retribution was invoked on the accursed person? Once again, the text in this regard is not very helpful, given its bareness and its lack of instructions to the chthonic deities. In fact, this message is found in the artefact – in both its shape and in the manipulations to which it was subjected – rather than in the text: firstly, the doll was moulded with the arms crossed and bound behind its back, a clear symbol of immobilisation; secondly, the doll lay in a coffin and was buried in a graveyard, which in turn point to the ultimate aim of the curse, namely, Mnesimachos’ death. Thus, the curser wished not only that their victim would lose the trial, but also that he would be made powerless forever. The violence inherent in such rituals is here entirely conveyed by its visual components, and demonstrates that their role was as important as that of the written text.

References

- Costabile, Felice (1999), ‘Κατάδεσμοι’, Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts (Abt. Athen), 114: 87–104 (esp. 87–91, no. 1).

- Costabile, Felice (2000), ‘Defixiones dal Kerameikos di Atene - II maledizioni processuali’, Minima Epigraphica et Papyrologica, 3: 37–122 (esp. 75–84).

- Jordan, David R. (1985), ‘A Survey of Greek Defixiones Not Included in the Special Corpora’, Greek Roman & Byzantine Studies, 26: 151–197 (esp. 156, no. 9).

- Jordan, David R. (1988), ‘New Archaeological Evidence for the Practice of Magic in Classical Athens’, Praktika of the 12th International Congress of Classical Archaeology, 4: 273–277 (esp. 275–276).

- Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum, vol. 21, no. 1093.

- Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum, vol. 49, no. 319.

- Trumpf, Jürgen (1958), ‘Fluchtafel und Rachepuppe’, Athenische Mitteilungen, 73: 94–102.

Description

Kerameikos Archaeological Museum, Athens

T148/VII,2 No. 19 (IB 12)

Material: lead

Dimensions: 11 × 6 cm

Provenance: Athens, around 400 BCE

Copyright notice

Fig. 1: Photo taken by Sara Chiarini.

Figs 2: and 3 photos taken from Costabile 2000, Fig. 19 and Fig. 20.

Reference note

Sara Chiarini, A Coffin, a Doll and a Curse: An ancient Artefact from an Athenian Cemetery

In: Wiebke Beyer, Karin Becker (eds): Artefact of the Month No 12, CSMC, Hamburg,

https://www.csmc.uni-hamburg.de/publications/aom/012-en.html