A ‘living fountain’ in bronze

Jochen Hermann Vennebusch

In a church, murmuring prayers in Latin, a priest slowly dips a metre-long candle three times into a font filled with fresh water, then reaches for a precious-looking vial and carefully pours a small amount of oil into the water. In the Middle Ages this mysterious ritual of consecrating the baptismal water was repeated once a year, during the Easter Vigil. A large number of baptismal fonts from the Middle Ages are still to be found in churches, and many of them show reliefs with intricate inscriptions. Some of these texts, especially in northern Germany, describe the baptismal fonts – often made of bronze – as a ‘living fountain’. Is this a plausible way of defining a bronze vessel whose contents are changed only once a year?

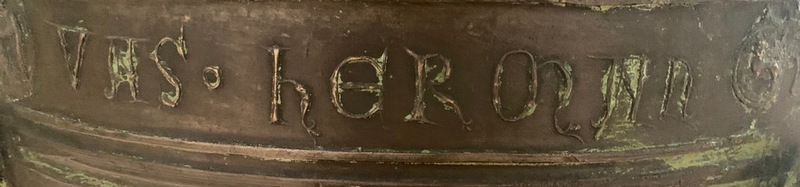

A baptismal font with such an inscription can be found directly before the chancel of the church in the convent of the Benedictine nuns in Ebstorf near Uelzen, Lower Saxony, Germany (Fig. 1). This ‘bronze font’ (‘font’ from Latin fons = fountain) is a round basin 95.5 cm in height with a diameter of 78.5 cm, narrowing slightly towards its lower rim (Fig. 1); it is carried by four male figures (Figs 1 and. 2) who seem to need all their strength to support the weight they are carrying, their feet apparently seeking a secure grip on the high standing rim. Three mouldings as well as the upper, slightly protruding, rim divide the wall of the font into four separate rings of differing heights. The top ring – between the upper rim and the first moulding – is smooth but has two solid handles which were previously used to fasten a cover; the latter was intended to keep the water pure but is no longer to be found. In the next (lower) ring a short section of the prayer used in the consecration of the baptismal water can be read in large lightly embossed letters (Fig. 3). The next ring on the outer wall contains numerous small reliefs some of which appear more than once. Various groups can be recognised: a small image of the crucifixion; several representations of Maria enthroned with the child Jesus on her lap; the badge of a pilgrim to Cologne showing an act of devotion to the Three Kings, embedded in a complex architectural motif (Fig. 4). In the lowest ring, just above the heads of the figures ‘supporting’ the font, a further inscription indicates in which year this bronze font was cast, and gives the identity of the person who created it (Fig. 5).

The man who cast this bronze font – in 1310 – is probably Hermannus Clocghetere, i.e. Hermann Glockengießer (lit. ‘bell-caster’) who operated a workshop in Lueneburg. A closer look at the lowest ring (Fig. 5) reveals a number of details which tell us how Hermann fashioned this font. A number of images in the ring between the two inscriptions (Fig. 4) are found several times: for example, the images of Maria with the child Jesus as well as the crucifixes. Furthermore, it seems that they were not formed from the outer side of the font, rather, they appear to be overlays added to the outer wall of the font. Work of this kind implies that the casting and moulding processes were very specific: first of all, a core made of bricks and covered with clay was made, reproducing the inside of the font. A further layer of clay was added by the caster, and was separated from the clay core by a thin layer of tallow; this second layer of clay was called the ‘shirt’ (German ‘Hemd’) and reproduced the actual font. The reliefs, made of wax, were then set into this second layer. We may assume that these reliefs were formed from pre-existing models and that they could easily be reproduced. Since baptismal fonts were cast with the opening face down the reliefs also had to be set ‘upside-down’. After the reliefs were set into the clay a third coat of clay was added, separated from the second by a further thin layer of tallow. Finally a fire was lit under all three clay formations (the core, the ‘shirt’ and the ‘coat’); thus, they dried and the wax reliefs melted leaving their imprint in the ‘coat’. After the ‘coat’ and ‘shirt’ had been separated from the core, the hardened ‘coat’ was put to one side. Subsequently, the reliefs and inscriptions which were to be embossed on the font, were carved or cut into the inner wall of the ‘coat’ in such a way that they would be filled by the liquid bronze. The caster then put the ‘coat’ over the core, this time without the ‘shirt’ (the model of the font). Thus, the space between the core and the ‘coat’ had the same form as the font and was filled with the bronze alloy (copper and tin). After the bronze cast had cooled down the inscriptions and reliefs were re-worked, the font polished and the ‘carriers’ (Figs 1 and 2) – which had been cast separately – would be soldered to the foot of the font.

It seems that the choice of reliefs on the baptismal font in Ebstorf – religious themes such as crosses or images of Jesus – entailed the repetition of some images, and, taken as a whole, the images do not represent a clear theme (Fig. 6). Since no reference is made here to the baptism of Jesus – a theme which might be expected on a baptismal font – this conclusion is perhaps self-evident. It seems that the artist was more interested in an abundance of themes, applying his reliefs – made from pre-existing models – to the wall of the font, between the two inscriptions. Here too we see the cast of a pilgrim’s badge from the cathedral in Cologne; this badge was given to those who made the pilgrimage to the shrine of the Three Kings in Cologne (Fig. 7). Such reliefs are found quite often on bronze baptismal fonts, but are more often found on bells; again one may draw the conclusion that these reliefs do not represent a clear theme, they are simply decorative; this suggestion is supported by the fact that these reliefs were made from models and were thus easy to reproduce.

However, the idea underlying the inscriptions on the bronze font in Erbstorf contrasts strongly with the reliefs: while the latter are almost certainly purely decorative and depict no specific theme, the inscriptions are written in gothic capital letters and are clearly related both to baptism and to the font itself. The inscriptions in the lower ring offer information concerning the production of the font: ‘ANNO D[omi]NI M CCC X FACTVM EST VAS HERMANVS ME FECIT’ – ‘In the year of the Lord 1310 this receptacle was made. Hermann made me’ (Fig. 5). At first sight the artist’s inclusion of an inscription on the font in which he himself – Hermann – is named may seem somewhat arrogant; and although the inscription is found in the lowest ring and the lettering is quite modest, nevertheless, Hermann’s name and the fact that he produced this baptismal font in the year 1310 is permanently engraved on this sacred object. Inasmuch as the inscription reveals the year of the casting and then the production of the font itself as the work of Hermann the caster, the master’s work is well valued, for the baptismal font speaks – quite literally – for itself. Furthermore, in the Middle Ages, the appearance of the name of the caster or artist on a liturgical object always expressed the artist’s yearning for God’s blessings.

Let us direct our attention to the inscription under the upper rim: ‘SIT · FONS · VIVVS · AQVA · REGENERANS · VNDA · PVRIFICA[ns]’ – ‘Be a living fountain, a water of life, a purifying wave’ (Fig. 3): Here, we see that, in contrast to the inscription naming Hermann (see above), the lettering is quite ornate; the contours of the individual capitals are well defined, some of them ending in the shape of a small leaf, while the interiors of the well-defined edgings show a finely engraved pattern. Thus, the design of the inscription on the baptismal font is well chosen and very accomplished; it declaims a short section of the prayer used to consecrate the baptismal water. In this invocation God is asked that the water be ‘a living fountain, a water of life, and a purifying wave’.

Despite the fact that the water is blessed only once a year – during the Easter ceremony – and that it remains in the font until the following Easter, and is not particularly life-giving – certainly not fresh from the source –, nevertheless, the life-giving quality of the water is highlighted. However, the emphasis here is spiritual rather than physical: in the earliest days of Christianity baptism was seen as a ‘Water of Rebirth’ (John 3: 3–5 / Titus 3: 5) through which the sins of the baptised person were forgiven. As the apostle Paul wrote (Romans 6), in baptism – seen as an initiation – the ‘former self’ is buried with Christ so that the baptised person may begin a new life and, at the end of time, may share in Christ’s resurrection. Seen from this perspective the baptismal water does not revive the body of the baptised person, rather – though the water is stale – this sacrament renews him at the spiritual level and the baptismal font is a source which gives him eternal life. Since part of the prayer of consecration of the baptismal water, spoken ritually only once a year, is cast in bronze and thus permanently engraved on the font, the prayer addressed to God – that he give the baptismal water a life-giving and purifying power – is, by its being read and by its sheer presence, continually renewed.

References

- Angenendt, Arnold (2006), ‘Taufe im Mittelalter’, in Bettina Seyderhelm (Hrsg.), Tausend Jahre Taufen in Mitteldeutschland. Ausst.-Kat. Dom Magdeburg 2006, Regensburg: Schnell & Steiner, 35–42.

- Kähler, Susanne (1993), ‘Lüneburg – Ausgangspunkt für die Verbreitung von Bronzetaufbecken am 14. Jahrhundert’, in Niederdeutsche Beiträge zur Kunstgeschichte, 32: 9–49.

- Eckhard, Michael (1997), ‘Die Ausstattung von Kirche und Nonnenchor des Klosters Ebstorf’, in Marianne Elster und Horst Hoffmann (eds), ‘In Treue und Hingabe’. 800 Jahre Kloster Ebstorf, Ebstorf: Selbstverlag, 189–196.

- Scheidt, Hubert (1935), Die Taufwasserweihegebete im Sinne vergleichender Liturgieforschung untersucht (Liturgiegeschichtliche Quellen und Forschungen, 29), Münster: Aschendorff 1935.

- Wahle, Stephan (2008), ‘Gestalt und Deutung der christlichen Initiation im mittelalterlichen lateinischen Westen’, in Christian Lange, Clemens Leonhard und Ralph Olbrich (eds), Die Taufe. Einführung in Geschichte und Praxis, Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 29–48.

Description

Ebstorf, Church of the Benedictine nunnery

Material: bronze

Dimensions: H: 95.5 cm; Ø: 78.5 cm

Provenance: Lüneburg, 1310

Copyright notice

All photos taken by Jochen Hermann Vennebusch

Reference note

Jochen Hermann Vennebusch, A ‘living fountain’ in bronze

In: Wiebke Beyer, Karin Becker (eds): Artefact of the Month No 11, CSMC, Hamburg,

https://www.csmc.uni-hamburg.de/publications/aom/011-en.html