A Survival from a Sixteenth-Century Bardic School

A Unique Irish Poetry Book

Mícheál Hoyne

Libraries do not preserve themselves; books – even ancient manuscripts – do not have intrinsic value, only the value people assign to them. In 1699 and 1700, the Welsh philologist and naturalist Edward Lhuyd toured Ireland. Lhuyd had a keen scholarly interest in the Celtic languages and he acquired many manuscripts in the Irish language. He himself did not have much Irish, so he was probably unaware that he was rescuing a small treasury of traditional Irish ‘bardic’ poetry – a rather plain and unattractive manuscript now known as the ‘Seifín Duanaire’. The manuscript is named after a mysterious poet whose work is preserved in that codex, and it is the single most important source extant for a whole species of versification about which we would otherwise know very little.

Literature in Irish stretches back to the seventh century. It served and was funded by the Gaelic aristocracy and later – after the acculturation of the Norman invaders who had arrived in the twelfth century – the learned classes also enjoyed the patronage of the blended Norman-Gaelic upper class. In the seventeenth century, the old Gaelic order buckled and finally collapsed under the stresses of the Tudor and Cromwellian conquests. When Lhuyd came to Ireland at the end of the seventeenth century, he found a civilisation in ruins. The hereditary families of professional praise-poets, historians and ‘Brehon’ legal scholars who had created the vast corpus of literature in Irish from the medieval and early modern periods were now surplus to requirements: they were the voice of a world that no longer existed. With their professions extinct, how could the old learned families make a living with their books? Meanwhile, there was not yet the sort of widespread interest in Ireland’s ancient literature in the wider world to create a market for Irish-language manuscripts. It is difficult to quantify the number of manuscripts – and indeed the literature they contained – that have simply been lost without a trace.

Though Lhuyd was not a wealthy man, he was able to purchase a substantial collection of manuscripts at a time when they were in danger of being lost forever, including the sorts of visually unspectacular scholars’ books that might not have attracted the attention of later manuscript collectors. Lhuyd had little Irish, and it is not clear that he was a particularly discerning collector: it is likely he acquired whatever he could get his hands on. After his death in 1709, Lhuyd’s manuscripts were sold and finally donated to Trinity College Dublin in 1786. It is therefore thanks to Lhuyd that the manuscript known as the ‘Seifín Duanaire’ survived.

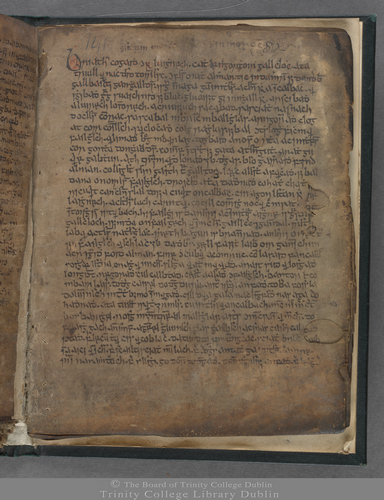

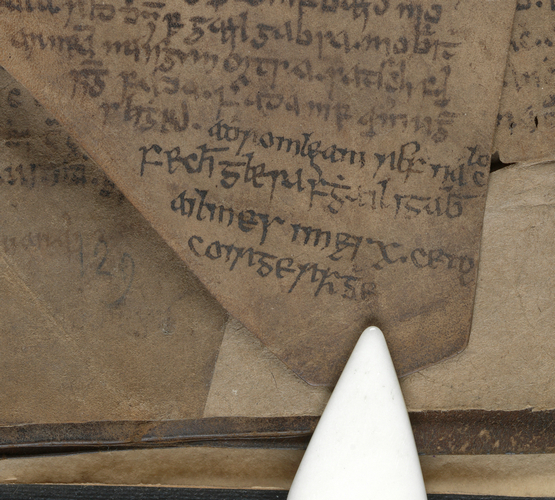

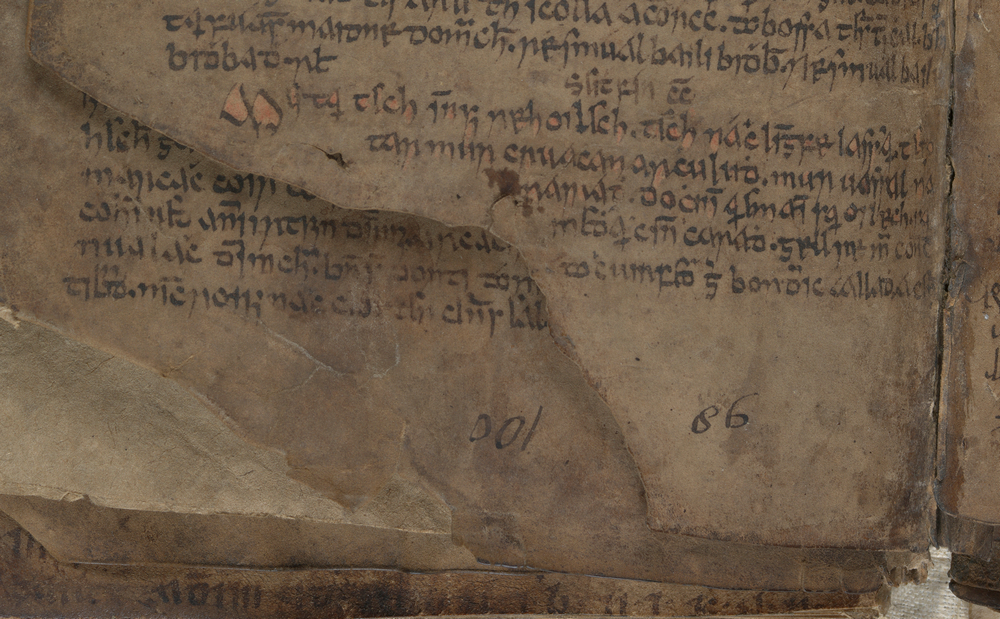

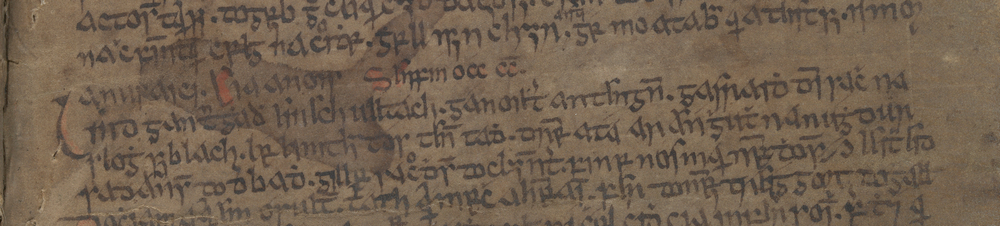

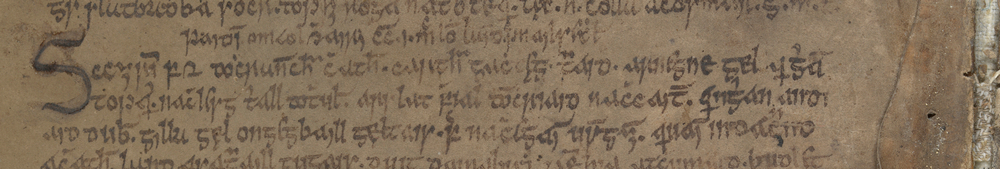

The Seifín Duanaire (Trinity College Dublin MS 1363 [olim H 4.22], XII) is a vellum manuscript. It is bound with a number of other manuscripts today, but these do not seem to be related to one another. Lhuyd had his manuscripts bound together in this way, and the many composite Irish manuscripts (originally distinct artefacts gathered together under a single shelfmark) currently held in Trinity College are part of his legacy. Our manuscript consists today of seventeen folios, though some material has certainly been lost. As is usual with Irish manuscripts, there was probably no cover (there certainly isn’t one now): even large Irish manuscripts were generally kept unbound. An unbound collection of vellum quires allowed the owner to lend out a single section without depriving himself of the rest of the book. Unfortunately, this gave the manuscripts less protection and meant that the sections most exposed were often subject to severe fading and damage. The vellum of the Seifín Poem-book is of poor quality, with many imperfections, irregularities and some prominent holes. Most pages are approximately 21.6 cm × 16.5 cm, but the manuscript also contains smaller irregular slips of vellum. These vellum scraps are sown into the main body of the manuscript and are not the result of damage to the book. The entire manuscript is written in the characteristic insular miniscule of medieval and early modern Irish manuscripts. The contents are all in Irish. There is at least one more or less contemporary probatio pennae (a short bit of text written to break in a new pen, but sometimes merely an excuse for someone other than the scribe to scribble his name on the book) by a hand other than that of the main scribe (Fig. 2), but otherwise the manuscript is wholly devoted to poetry. The manuscript has no ornamentation besides a little rubrication here and there, often marking the beginning of a poem but sometimes with no clear purpose. Lhuyd added page numbers, but as he bound multiple manuscripts together the pagination is continuous across several distinct books; in the case of our manuscript, which was originally bound upside down, the page-numbers are at the bottom of the page (Fig. 3). Hardly any space is wasted and the page often feels crowded. As we will see, the contents are all metrical, but the scribe makes little effort to show the metrical structure of the texts he transcribes (by clearly dividing lines of verse, say): he writes all the poems as if they were prose, filling up the whole text block and only dividing metrical lines by means of a simple full stop. The manuscript is clearly not a presentation manuscript for a lordly patron; it is rather a more humble scholarly textbook.

In two colophons at the end of poems the scribe Tanaidhe Ó Maoil Chonaire names himself and we learn that the manuscript (or most of it) was written in the house of Doighre Ó Duibhgeannáin in Drumcollop, Co. Leitrim, and that Tanaidhe wrote it for Cú Chonnacht Ó Duibhgeannáin and his sons. Doighre Ó Duibhgeannáin, in whose house our scribe worked, died in 1589; we don’t know exactly how he was related to Cú Chonnacht Ó Duibhgeannáin. Both the scribe of this manuscript and his host belonged to distinguished families of seanchaidhe or professional historians. Seanchaidhe were responsible for compiling, maintaining and sometimes even fabricating the genealogies of their aristocratic patrons; they composed prose tracts on the illustrious history and the rights and privileges of their employers; and they wrote elaborate praise-poems for them drawing on this material. All of this required special training, and in particular the craft of poetry had to be learned. The metrical system of Irish syllabic or ‘bardic’ poetry was very complex. In addition, poets were expected to adhere to a refined literary idiom, which is described in extraordinary detail in contemporary linguistic tracts, drawing on a canon formed from the work of master-poets who lived in the thirteenth, fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Bardic poets were expected to undergo at least seven years of training in specialist schools, and some might continue their studies longer still. In the period that the ancient universities were developing in mainland Europe and in Britain, specialist schools of history, law and poetry formed throughout Ireland for the hereditary learned families. The rules of syllabic poetry and the literary idiom were the foundation of the education offered in these schools.

This is the context in which we must read the Seifín Duanaire. It consists of a collection of poems composed in the fifteenth century. Most are by a poet named Seifín Mór and his sons. Seifín is shrouded in mystery (even his surname is unknown), but he must once have been a famous figure whose work was widely studied in bardic schools, as he is cited in the linguistic tracts. All of the poems are composed in a form of verse known as brúilingeacht, which is dominated by the type of rhyme known as comhardadh brisde (or ‘broken rhyme’) and is found in a small number of elaborate metres. This form of verse is particularly associated with hereditary historians like the Ó Maoil Conaire family and the Ó Duibhgeannáin family. It appears that the Seifín Duanaire is a kind of sourcebook, a collection of ‘classic’ examples of the metrical form which trainee seanchaidhe had to master, well-regarded poems from the golden age of bardic poetry which they were to imitate or to draw on in the course of their own careers. As it happens, very little of this type of verse has come down to us: the Seifín Duanaire preserves three-quarters of the extant corpus of brúilingeacht, and most of these poems are preserved nowhere else. The poems themselves are invaluable historical documents, containing vivid accounts of court life and the careers of Gaelic lords. One is a religious poem, but most praise-poems for Gaelic aristocrats, extolling their ancestry, their virtuous conduct, their patronage of the learned orders, and their skill in battle. Composed at a time when tower-houses were proliferating in Ireland, they feature unique descriptions of the tapestries and furnishings of Gaelic houses, for which there is no evidence in the archaeological record. Some of these poems were cited in the grammatical and metrical treatises of the bardic poets, which shows that they were well regarded, even though for most we have only this single copy – another sign of how much material we have lost, for copies of poems studied in the bardic schools must once have been widely available.

We know almost nothing about the Tanaidhe Ó Maoil Chonaire who wrote most of our manuscript, Doighre Ó Duibhgeannáin, in whose house he stayed, or Cú Chonnacht Ó Duibhgeannáin, for whom he wrote. At times Tanaidhe’s hand seems rather immature and he makes quite a few copying errors. I suspect our scribe was a trainee poet. It was not unusual for learned poets to be sent to schools run by other families to learn their craft. It could be that while he was a student at the Ó Duibhgeannáin school Tanaidhe was asked to make a copy of these important texts in the library of his teacher Cú Chonnacht Ó Duibhgeannáin for his teacher’s relative, Doighre. In turn, Doighre may have wished to use them to instruct his own sons or other students. But this is speculation. Some of these men must have written poems too, but to my knowledge none of these have survived. We can only guess at the extent of their libraries. Edward Lhuyd was probably not the most discerning collector of manuscripts: he gathered up what remnants he could find of a dying civilisation, books (some of them quite plain and inconspicuous) which no longer had value among the people who produced them but which would find new value at the hands of modern philologists. Edward Lhuyd ensured that a whole class of verse and versifier was not forgotten and that scholars of Irish syllabic poetry and Gaelic Irish history have a wealth of material on which to work, much of which still remains to be edited and translated.

References

- Bergin, Osborn (1970), Irish Bardic Poetry, Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies.

- Emery, Frank (1971), Edward Lhuyd F.R.S 1660–1709, Caedydd: Gwasg Prifysgol Cymru.

- McManus, Damian (2004), ‘The bardic poet as teacher, student and critic: a context for the Grammatical Tracts’, in Cathal G. Ó Háinle and Donald E. Meek (eds): Unity in Diversity: Studies in Irish and Scottish Gaelic Language, Literature and History, Dublin: Trinity College, 97–124.

- Ó Cuív, Brian (1973), The Irish Bardic duanaire or ‘poem-book’: The R.I. Best Memorial Lecture, Dublin: Malton Press for the R.I. Best Memorial Trust.

- Walsh, Paul (1947), Irish Men of Learning: Studies, Dublin: Three Candles Press.

Description

Present Location: Manuscripts Library, Trinity College Dublin

Shelfmark: 1363, XII

Material: Vellum, 17 folios

Dimensions: 21.6 cm (w) × 16.5 cm (h)

Provenance: Drumcollop, Co. Leitrim, Ireland; late sixteenth century

Copyright notice

Copyright for all images: The Board of Trinity College Dublin

Reference note

Mícheál Hoyne, A Survival from a sixteenth-century Bardic School: a unique Irish Poetry Book

In: Wiebke Beyer, Karin Becker (eds): Artefact of the Month No 9, CSMC, Hamburg,

https://www.csmc.uni-hamburg.de/publications/aom/009-en.html