One Manuscript and Three Persecutions

The Journey of the Vienna Hebrew Prophets and Hagiographa

Ilona Steimann

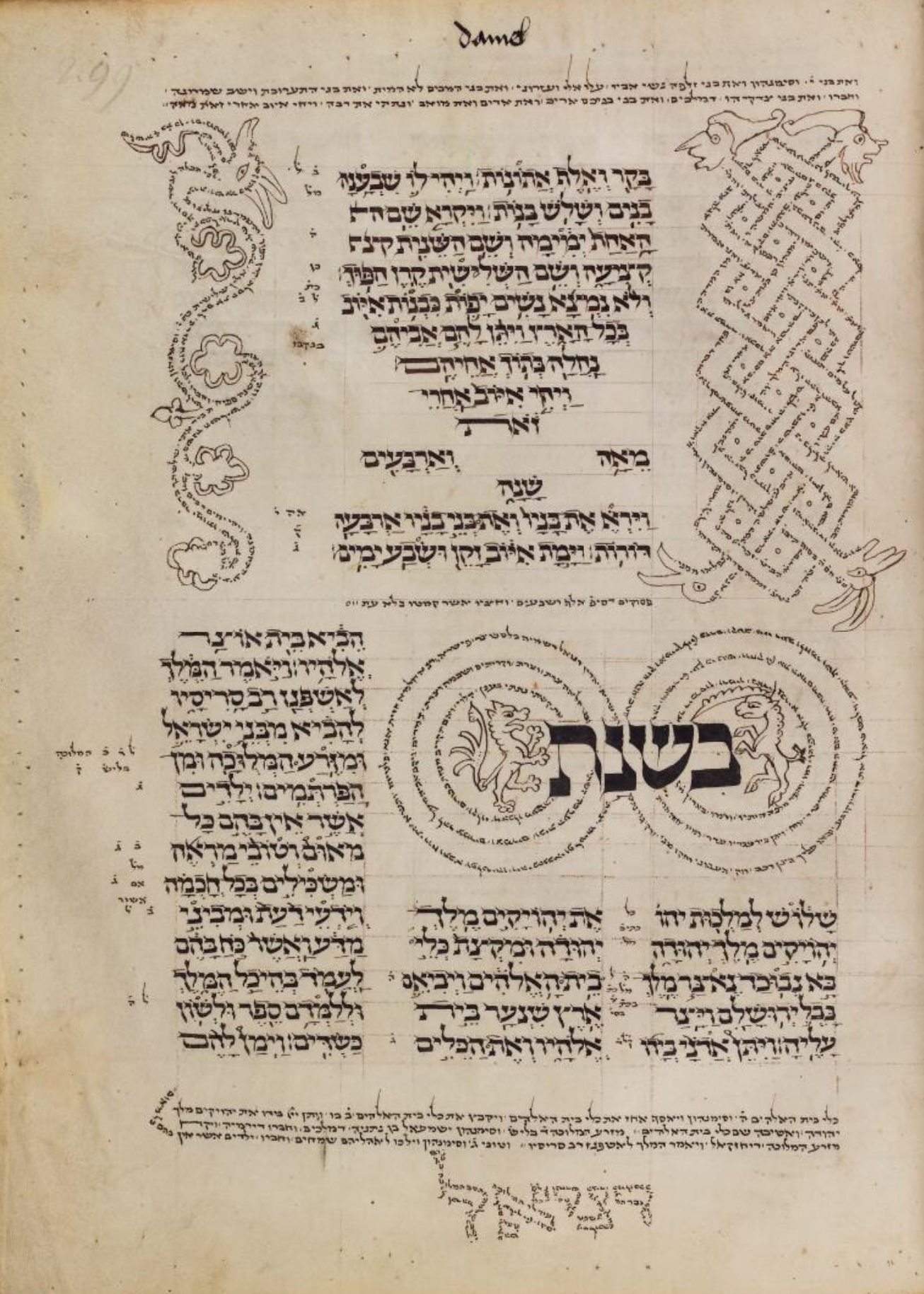

As a result of false allegations against the Jews, in which the existence of a Hussite-Jewish conspiracy was claimed, and various anti-Christian crimes were fabricated, Jews were expelled from Vienna and its environs in 1421 – an event that became known as the Vienna Gezerah (edict). In the wake of the expulsions, various Jewish possessions were confiscated by Duke Albrecht V, including numerous Jewish manuscripts. About a month later, the University of Vienna commissioned its theologians to acquire Hebrew books from the duke, books that could be useful for the university and the theological faculty. Under these circumstances, the theologians obtained an old Hebrew codex that contained the second and the third parts of the Old Testament, i.e. the Prophets and the Hagiographa (Fig. 1). However, the Vienna Gezerah was not the first persecution of Jews this manuscript had faced; the manuscript had witnessed two earlier pogroms, each of them echoed on its pages.

The Vienna Prophets and Hagiographa is a parchment codex (368 leaves) of Franconian origin, produced in 1298/99. In accordance with Jewish tradition, the Prophets (fols 1v–226r) contain the Former Prophets (Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings) and the Latter Prophets (Jeremiah, Isaiah, Ezekiel, and the Twelve, or Minor Prophets, such as Hosea, Joel, Amos, and others). The Hagiographa (fols 227 v–368r), separated from the Prophets by two blank pages, comprises the poetic and historical books: the Song of Songs, Ruth, Lamentations, etc. Normally, such Hebrew Bibles were produced in either two volumes (Pentateuch and Prophets-Hagiographa) or three volumes (Pentateuch, Prophets, and Hagiographa), suggesting that the Vienna manuscript is the second volume of the entire Bible, whose first volume, the Pentateuch, has not come down to us.

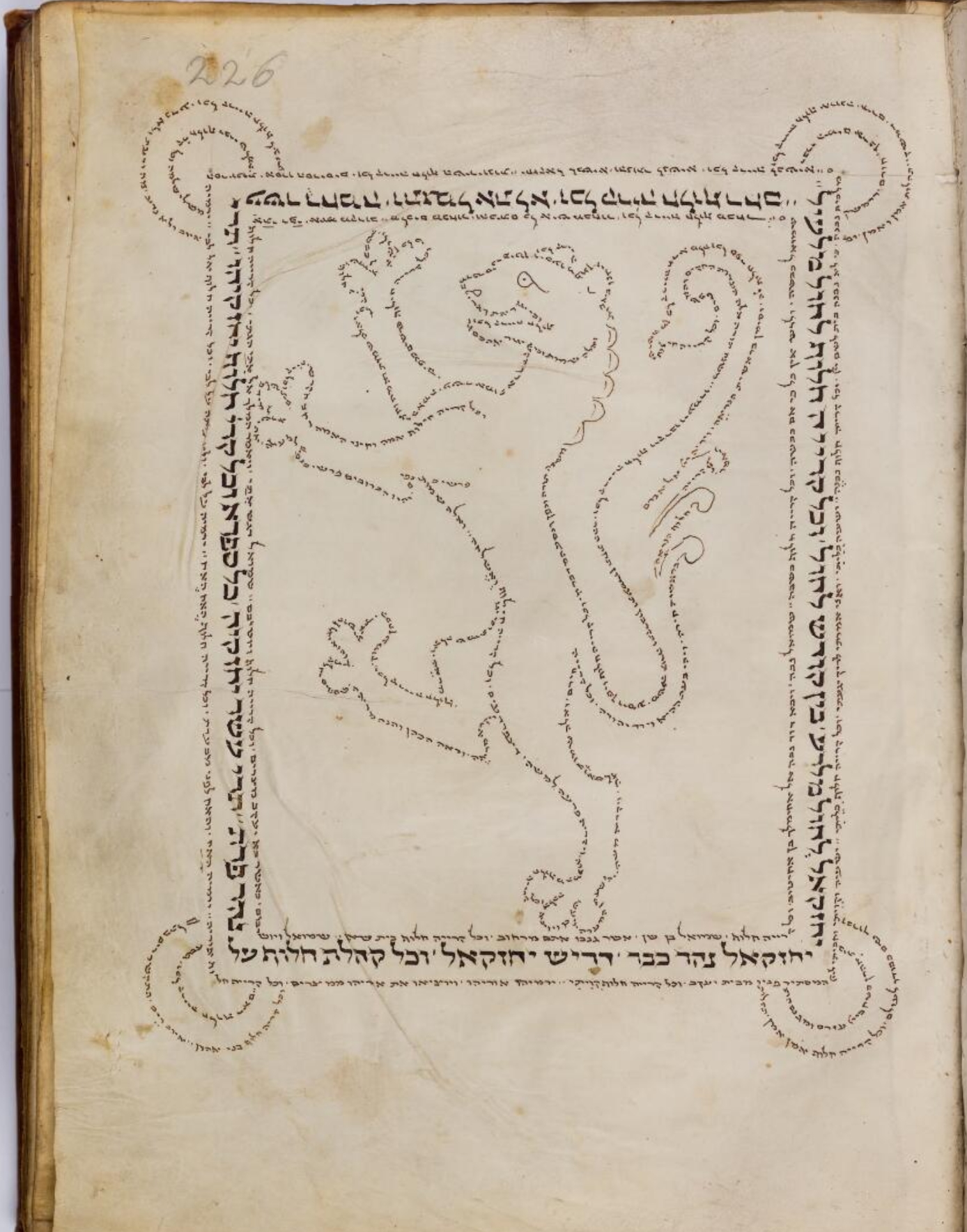

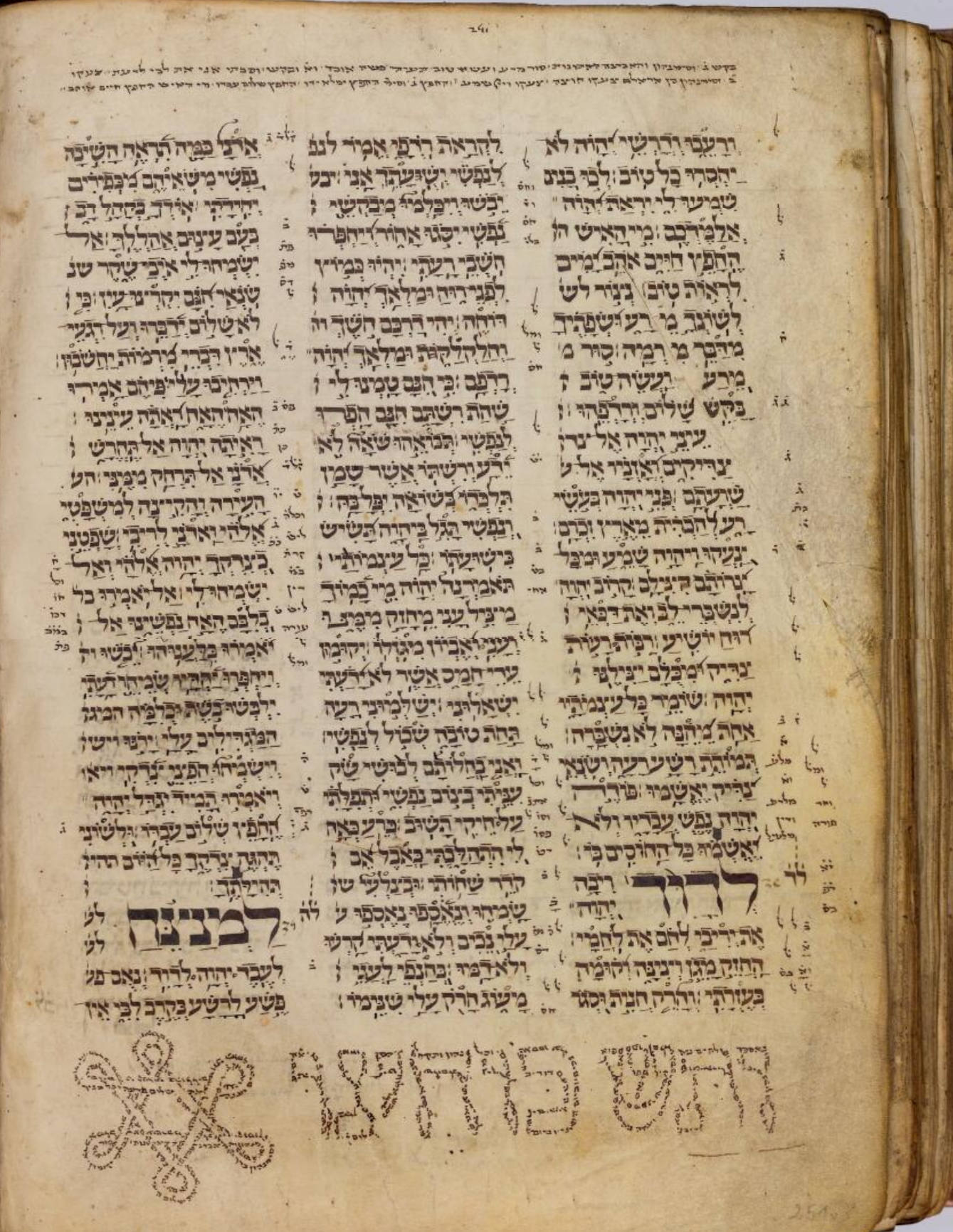

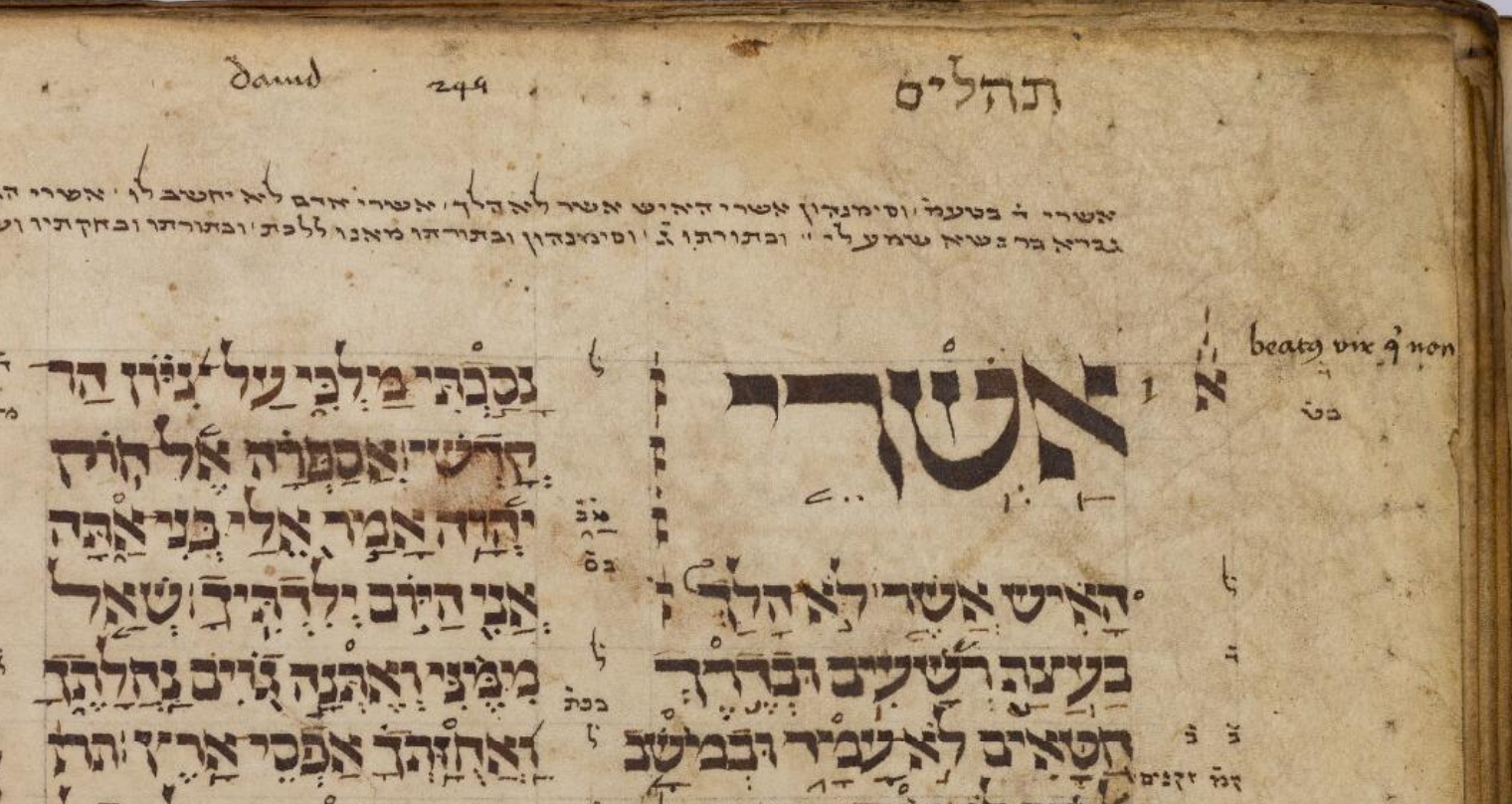

The text, in dark brown ink, was copied in two columns for Prophets and three columns for Hagiographa; both types of layout were common in Hebrew biblical codices. The last pages of the Hagiographa are arranged in one column, a visual indication of the end of the manuscript. The text of the Vienna Prophets and Hagiographa is written using the traditional elements of transmission of the biblical text such as accentuation and vocalization above and below the consonant letters. The main text is accompanied by large and small masorah, e.g. comments on spelling and pronunciation, as well as on the occurrence of certain words in the text; other lexical notes are written between the columns and in the margins. Masoretic annotations are part of the Jewish oral tradition, first written by the Masoretes in the seventh and eighth centuries in order to transmit the correct reading of the Bible, and they and are often found in biblical manuscripts. As in many other codices of the Bible, the minute script of the masorah in the Vienna Prophets and Hagiographa takes the form of micrographic decorative patterns and figurative images. Such decorative elements mainly appear at the beginning and end of the biblical books (Fig. 2).

Because of the complexity of biblical manuscripts, their production would involve a number of people, each responsible for a different task. The scribes of the consonant text were not necessarily experts in vocalization, accentuation, and Masoretic annotations. Therefore, the tasks of copying the text, vocalizing, accentuating, and annotating it would be divided between different persons, each of whom would write a colophon containing information about his copying process. While the three scribes who copied the text of the Vienna Prophets and Hagiographa left no colophons, Aberzush, the scribe who was responsible for the vocalization and the masorah, wrote a detailed colophon the letters of which were formed by masorah, thus creating a text within a text. The colophon occupies the lower margins of forty successive pages of the Psalter (fols 248v–268r; Fig. 3); neither its length nor such a degree of elaboration are common in Jewish manuscript culture.

The colophon tells of the Rintfleisch massacres in 1298 (named after a German knight, the instigator of the pogroms) when thousands of Jews including members of Aberzush’s own family were killed in southwest and central Germany:

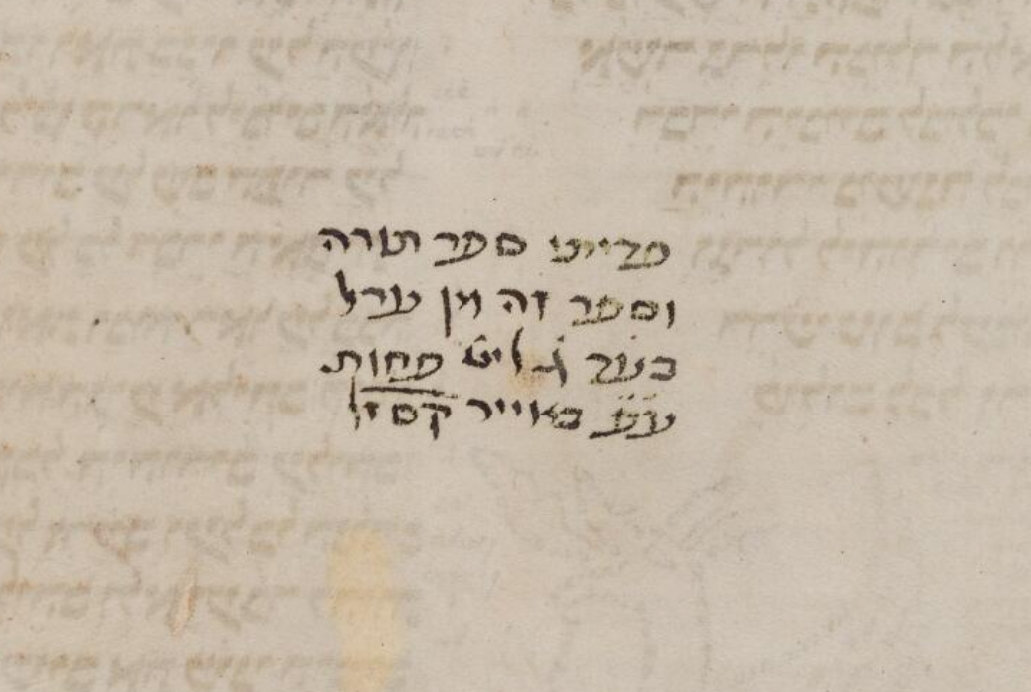

It is not known for whom this manuscript was produced and who owned it after the Rintfleisch pogroms. Those Jews who survived the massacres and managed to flee resettled in other regions of the Empire. They brought their precious manuscripts with them one of which is the Vienna Prophets and Hagiographa. The next stop in the itinerary of this volume was Vienna. In this case too, the manuscript appears in the context of anti-Jewish violence. When in 1406 a fire broke out in the Vienna synagogue, burghers and students of the university seized the opportunity to attack the Jews and to plunder Jewish houses. Among the looted property were Jewish manuscripts. Christians were well aware of the Jewish practice of redeeming manuscripts from non-Jewish hands, often at any price. The Vienna Prophets and Hagiographa, together with an unidentified Torah scroll, were thus resold to a Jew in 1407 at a high price. The new owner documented their redemption with the following words, which he wrote in the Vienna Prophets and Hagiographa: ‘I have redeemed a Torah scroll and this book from a gentile for three pounds minus seventy pfennigs in the month of April, 1407’ (Fig. 4). Since a Torah scroll was usually preserved in a synagogue, it is possible that both the scroll and the Vienna Prophets and Hagiographa were plundered directly from the Viennese synagogue during the course of the fire.

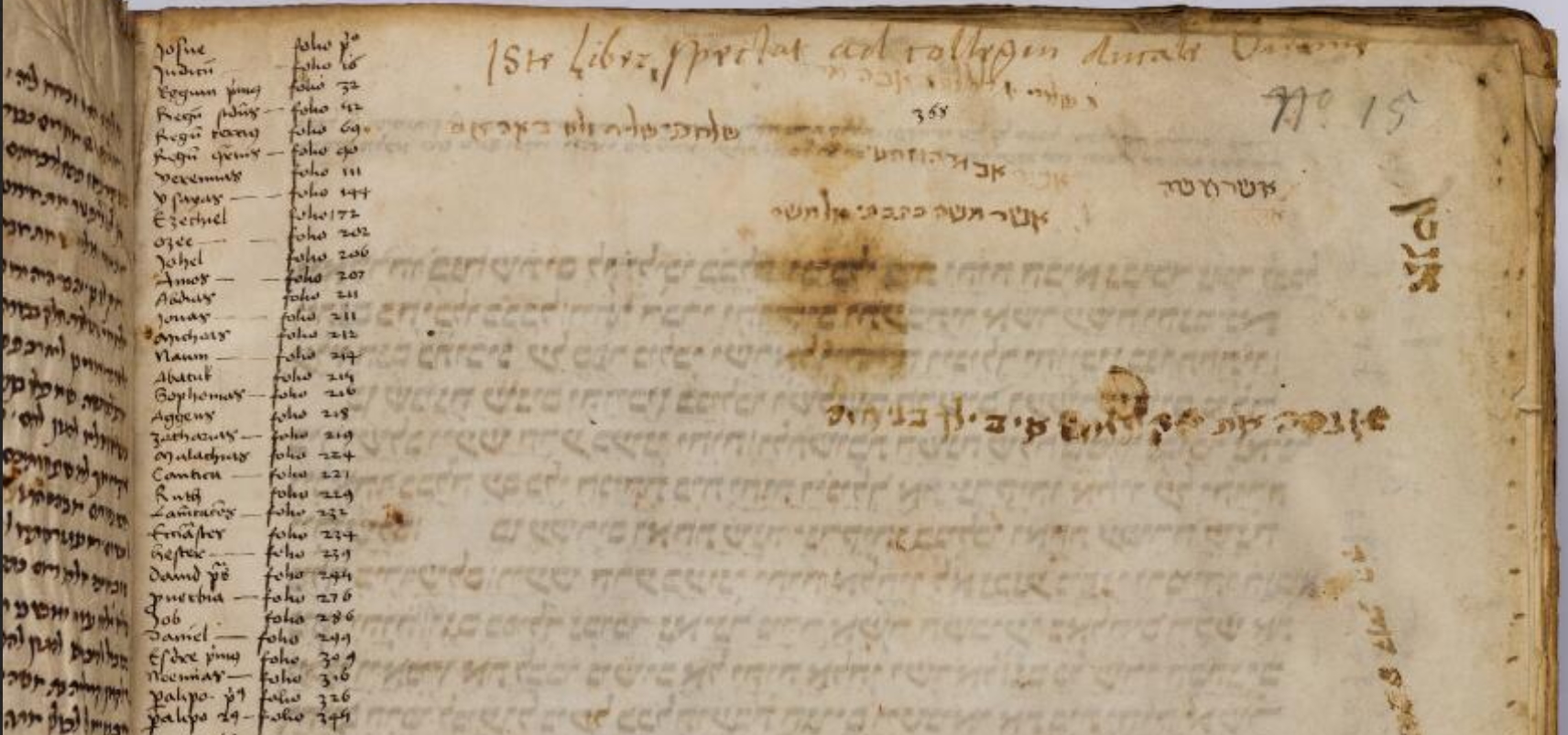

In 1421, when Albrecht V confiscated Jewish books during the Vienna Gezerah, the Vienna Prophets and Hagiographa fell once more into the hands of Christians. The theologians of the Vienna University must have acquired this manuscript together with several other Hebrew volumes from the confiscated stock, and housed them in the Collegium Ducale (Duke’s College, 1384–1623) (Fig. 5). Most of the Hebrew manuscripts obtained by the Collegium were biblical codices which the theologians read through the lens of ‘Christian truth’ and thereby hoped to use them as evidence for the veracity of their own religion. To adapt the Vienna Prophets and Hagiographa to Christian use, the members of the Collegium added running Latin titles to the Hebrew text, divided the chapters and translated some of their opening lines into Latin in accordance with the Vulgate (Fig. 6). They also wrote a Latin list of the biblical books contained in this volume (fol. 368v). These additions were intended as navigation aids for readers not fluent in Hebrew and, taken as a whole, they suggest that an attempt was made to build a bridge between the Hebrew Bible and the Vulgate.

Although the theologians showed an obvious interest in the Hebraica they had just obtained, over the course of time the Collegium’s Hebrew volumes were neglected. As the librarian of the Vienna Court Library (the precursor of the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek), Sebastian Tengnagel, wrote to King Matthias in 1611, some twelve or thirteen large Hebrew volumes belonging to the university were not in use, and were gradually being destroyed by bookworms and moths. Tengnagel, therefore, asked the king to transfer these manuscripts to the Court Library, suggesting that they would be better preserved there. However, despite Tengnagel’s efforts, it was more than a hundred years before the university’s Hebrew codices became part of the Court Library, when the university book holdings and the Court Library were united in 1756. In the Court Library, the Vienna Prophets and Hagiographa was rebound, possibly because its original/older binding had been damaged as a result of the bad conditions that Tengnagel had described.

The journey of the Vienna Prophets and Hagiographa between different geographical areas (from Franconia to Vienna) and religious traditions (Jewish and Christian) is reflected in the manuscript’s margins. The margins not only mirror the traumatic events of medieval Jewish life, as a result of which the manuscript changed hands, but they also demonstrate that the meaning of any text is in the eye of the beholder. The same manuscript, interpreted differently and adjusted accordingly, could serve the needs of different religious groups.

References

- Beit-Arié, Malachi, Hebrew Codicology: Historical and Comparative Typology of Hebrew Medieval Codices based on the Documentation of the Extant Dated Manuscripts Using a Quantitative Approach , preprint internet English version 0.4, 188–189.

https://web.nli.org.il/sites/NLI/English/collections/manuscripts/hebrewcodicology/Documents/Hebrew-Codicology-continuously-updated-online-version-ENG.pdf - Ginsburg, Christian D. (1966), Introduction to the Massoretico-Critical Edition of the Hebrew Bible, New York: Ketav, 777–778.

- Schwarz, Arthur Z. (1925), Die hebräischen Handschriften der Nationalbibliothek in Wien , Museion, 2, Vienna: Strache, 6–7.

- Sirat, Colette (2002), Hebrew Manuscripts of the Middle Ages, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 225 .

Description

Library: Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek

Shelfmark: Cod. hebr. 16

Origin: Franconia, 1298/99

Material: Parchment, II + 368 + 1 leaves

Size: ca. 245 × ca. 330 mm

Languages: Hebrew with Latin annotations

Binding: Eighteenth-century brown leather binding on the wooden boards

Provenance: Vienna, Collegium Ducale and later the Court Library

Digital images of Cod. hebr. 16 from the collections of Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, accessible at Ktiv Project, the National Library of Israel.

Reference note

Ilona Steimann, One Manuscript and Three Persecutions: The Journey of the Vienna Hebrew Prophets and Hagiographa

In: Wiebke Beyer, Karin Becker (eds): Artefact of the Month No 8, CSMC, Hamburg,

https://www.csmc.uni-hamburg.de/publications/aom/008-en.html