A Scoop of Filial Piety?

Ondřej Škrabal

As in many other pre-modern civilisations, inscriptions in ancient China did not generally contain any sentential or phrasal punctuation. This was in stark contrast to manuscripts of the same period which often display a variety of punctuation practices. However, an ancient bronze scoop measure unearthed in 1982 in Liquan County, Shaanxi Province, China, bears a short but thoroughly punctuated inscription on its underside. Who made the unusual decision to punctuate this inscription, and why?

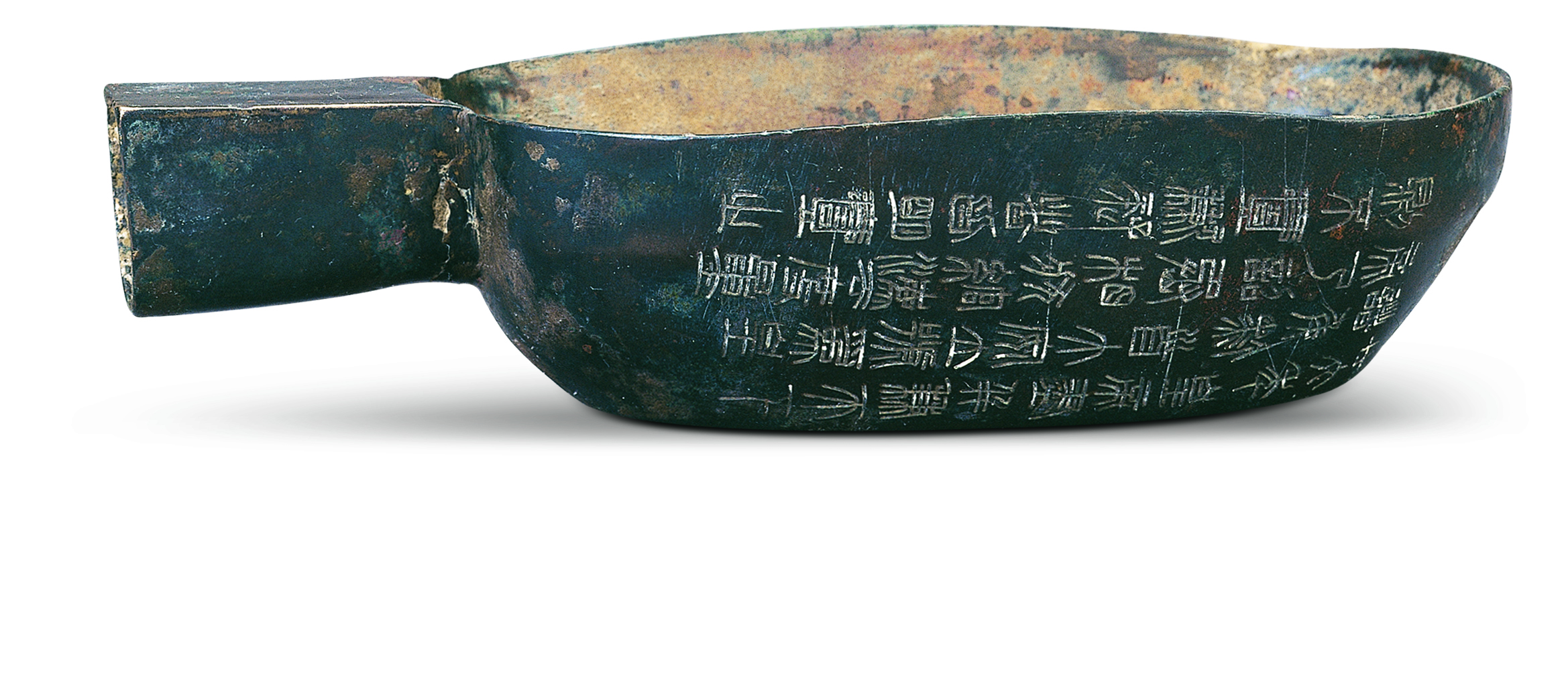

The bronze scoop measure described here is known as the ‘measure from the Private Treasury of the Northern Palace’ (Bei Sifu liang). The object itself is not unique. Quite the contrary: in the ancient Chinese state of Qin, one of the seven ‘warring states’ in the third century BCE, such bronze measures were mass-produced. The scoop, which is now housed in the Shaanxi History Museum in Xi’an (Fig. 1), is 20.8 cm long at its mouth, 12.5 cm wide and its slightly slanting walls are 6.1 cm high. It weighs 1,275 g and its capacity is 980 ml, i.e. ‘half a dou’. It has a solid socket through which it was mounted onto a wooden shaft, and it was probably used for measuring out grain at the Qin court. What makes this object special is the punctuated inscription engraved on its underside in 209 BCE.

In order to understand exactly why this inscription was produced, we need to go back a few years. In the year 221 BCE the First Emperor of Qin (259–210 BCE) concluded his decade-long campaign of conquests, during which his state, Qin, annexed all the states of the ancient Chinese realm and united them into a colossal empire. In order to overcome the disparities between the recently conquered regions and to promote the idea of the newly established political entity, former Qin laws, script and standards were now promulgated as empire-wide norms, affecting everything from units of weight and measure to the gauge of chariot wheels. In some cases the challenge of achieving standardisation was aided by epigraphic means. All newly produced weights and measures were inscribed with the following abridged version of an imperial decree:

In the twenty-sixth year [of his reign], the Emperor unified the lands of the realm completely. The populace enjoyed great peace, [and he] established the title ‘Emperor’. [He] then commanded chancellors [Wei] Zhuang [and Wang] Wan: ‘As for norms and standards, those that are divergent or doubtful are all to be clarified and unified.’

Moreover, weights and measures produced before the unification but conforming to Qin standards – including those produced previously in the state of Qin – also had to be certified for use by the inscription of this text, and this is the case for the bronze scoop measure described here. After the certification of weights and measures was declared, the abridged decree was engraved – most likely using an iron graver – on the outer right wall of the scoop (see Fig. 1). The inscription is written in small seal script, a new script form devised in Qin specifically for epigraphic purposes.

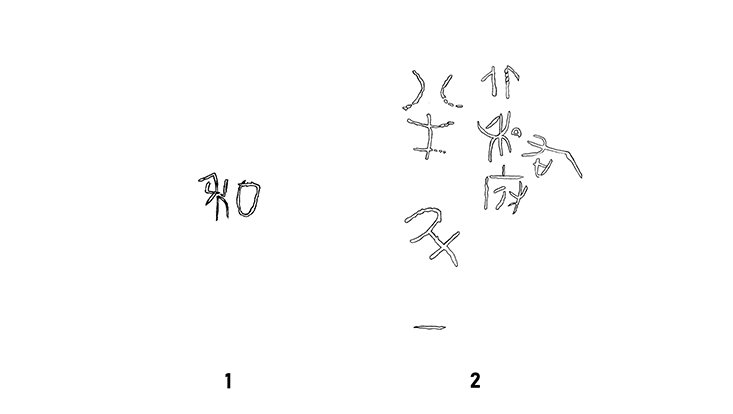

However, this was not the first time that the scoop had been inscribed. Its first inscription was a character perfunctorily chiselled on the outer left wall of the socket (Fig. 2:1). It reads si, ‘Private’, short for the Private Treasury of the Northern Palace. This institution was part of the palace administration at the Qin court and provided for the personal needs of the Qin queen. The chiselling was probably done in the workshop in which the measure was produced in order to indicate the scoop’s destination.

After the scoop was delivered to the Treasury, it was examined, recorded and a second shallow inscription was engraved on the upper side of the socket to indicate both its capacity and the institution where it would be used (Fig. 2:2). Two more characters in a different hand were added somewhat later; they further specify the place of use and the serial number of the object. These short inscriptions are all written in a more ancient script form:

Right [department(?)].

Private Treasury of the Northern [Palace].

Half a dou. [Number] one.

Only after years of use was the First Emperor’s certification added to the scoop in 221 BCE.

Eleven years later, following the Emperor’s sudden death, his eighteenth and youngest son unexpectedly assumed the throne and became the Second Emperor (r. 210–207 BCE). To consolidate the legitimacy of his rule, and under the pretext of highlighting the merits of his father, he issued a supplement to the First Emperor’s certification inscription which was to be engraved right next to it – also in small seal script. In this way, he made use of the medium that had proved so effective in his father’s state propaganda, with the consequence that newly produced weights and measures were now inscribed with both the original certification and the supplement. Some of the utensils already in circulation were recalled and their inscriptions supplemented in the capital city, while others were re-inscribed locally.

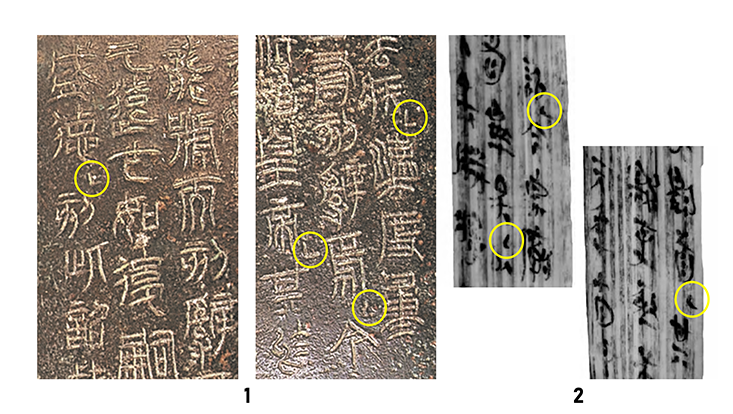

The Private Treasury scoop described here illustrates some of the peculiarities that occasionally emerged during the supplementing process. As mentioned above, the original certification was engraved on the outer right wall of the scoop. However, since the Chinese script was written vertically from right to left, and the first column was positioned on the lower part of the wall, the last column was written just below the rim, leaving no space on this wall for the supplement – the very supplement that was to be added after the First Emperor’s certification. The craftsmen had a problem: simply adding the text on the underside or on the opposite wall was deemed inappropriate, as it would then appear to precede the original inscription. They found a canny solution: they simply engraved the First Emperor’s inscription again on the opposite wall (this time beginning under the rim) and continued with the Second Emperor’s addendum on the underside of the measure (Fig. 3). Significantly, the supplement is punctuated by four L-shaped marks (highlighted in Fig. 4:1):

In the first year [of his reign, the Second Emperor’s] decision instructed chancellors [Li] Si and [Feng] Quji∟: ‘The standard measures were all established by the First Emperor, and all of them bear inscriptions [concerning this].∟Now [I] continue to use the title [‘Emperor’], but the inscriptions do not refer to [the previous emperor as] the First Emperor.∟After a long period of time, it might seem like [the standardisation] was done by [one of his] successors [and thus] fail to praise [the First Emperor’s] completed achievement and abundant virtue.∟Inscribe this instruction to the left of (=after) the previous inscriptions so there will be no doubt [about it].’

The marks serve essentially as caesuras, facilitating perusal of the inscription. The same L-shaped marks are well known from contemporaneous manuscripts, especially from legal texts written in ink on bamboo-strip rolls. Indeed, a wooden-board witness of another decree issued by the Second Emperor in the first year of his reign was recently unearthed from an ancient well in Tuzishan, Hunan Province; it also contains these L-shaped marks (Fig. 4:2).

One of the unresolved issues concerning these marks is the question of whether the punctuation was part of the original administrative or legal document issued by the central government or whether it was only a later addition made by the local officials or other users during further copying or perusal. Given the epigraphic evidence, the first option seems the more likely – at least for the reign of the Second Emperor – as our scoop is by no means an isolated case: three further artefacts containing the punctuated supplementary inscription are known today, and all of them employ the L-shaped marks in the same manner. The punctuation in these inscriptions was clearly not produced by their readers, but by engravers who copied them from a manuscript exemplar. This exemplar was not the full imperial decree, however, but an epigraphic template issued and tailored by the central government for purposes of the new medium. The template itself was not meant to be read out loud or publicly displayed; its sole purpose was to facilitate the inscription of the text onto such objects. The supplement contained 60 characters which, along with the 40 characters of the First Emperor’s certification, made 100 characters in all; thus, both texts were apparently the product of careful planning. Since the templates were distributed by the central government, the punctuation must also have been decided on by central draftsmen.

The question is, for what reason? Scholars have argued that, since the bronze weights and measures were disseminated to state institutions and marketplaces across the empire, they were ideal avenues for the mass communication of state ideology. The programmatic punctuation of the Second Emperor’s inscriptions bears out this line of thought as it reveals that these texts were indeed expected to be read out loud at their destinations, and that the state attached importance to the accurate delivery of the supplemented message – and only the supplemented message, since none of the certification inscriptions are punctuated. As the primary agenda of this addendum was to draw attention to the Second Emperor’s refusal to appropriate his father’s achievements, the incentive for punctuating his inscriptions is now clear: it was done to enhance the promotion of a stylised image of a filial and respectful ruler, a strategy devised to consolidate the perceived legitimacy of his questionable succession.

References

- Caldwell, Ernest (2018), Writing Chinese Laws: The Form and Function of Legal Statutes Found in the Qin Shuihudi Corpus, London: Routledge.

- Chen Mengdong 陳孟東 (1987), ‘Shaanxi faxian yi jian liang zhao Qin tuo liang’ 陝西發現一件兩詔秦橢量, Wenbo 文博, 2: 26–27.

- Hou Xueshu 侯學書 (2004), ‘Qin zhao zhuke yu quan liang zhengzhi mudi kao’ 秦詔鑄刻於權量政治目的考, Jianghai xuekan 江海學刊 6: 123–128.

- Hunan sheng wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo 湖南省文物考古研究所, Yiyang shi wenwuchu 益阳市文物处 (2016), ‘Hunan Yiyang Tuzishan yizhi jiu hao jing fajue jianbao’ 湖南益陽兔子山遺址九號井發掘簡報, Wenwu 文物, 5: 32–48.

- Li Guangjun 李光軍 (1987), ‘Liang Guang chutu Xi-Han qiwu mingwen guanming kao’ 兩廣出土西漢器物銘文官名考, Wenbo 文博 3: 32–38+31.

- Li, Kin Sum (Sammy) (2017), ‘To Rule by Manufacture: Measurement Regulation and Metal Weight Production in the Qin Empire’, T’oung Pao 1–3: 1–32.

- Li, Xueqin (1985), Eastern Zhou and Qin Civilizations (translated by K. C. Chang), New Haven: Yale University Press, 240–246.

- Ma Ji 馬驥, Yong Zhong 詠鐘 (1992), ‘Shaanxi Huaxian faxian Qin liang zhao tong jun quan’ 陝西華縣發現秦兩詔銅鈞權, Wenbo 文博 1: 3–4+40.

- Sanft, Charles (2014), Communication and Cooperation in Early China: Publicizing the Qin Dynasty , Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Staack, Thies (2020), ‘From Copies of Individual Decrees to Compilations of Written Law: On Paratextual Framing in Early Chinese Legal Manuscripts’, in Antonella Brita, Giovanni Ciotti, Florinda de Simini, and Amneris Roselli (eds.), Copying Manuscripts: Textual and Material Craftsmanship. Napoli: UniorPress, 183–241.

- Zhang Tian’en 張天恩 (2016), Shaanxi jinwen jicheng 陝西金文集成, vol. 10, Xi’an: San Qin.

- Zhu Jieyuan 朱捷元 (1988), ‘Guanyu “Liang zhao Qin tuo liang” de dingming ji qita’ 關於“兩詔秦橢量”的定名及其它, Wenbo 文博 4: 39–40.

Description

Location: Shaanxi History Museum 陝西歷史博物館, Xi’an, PRC

Accession number: 八七98

Material: bronze

Dimensions: 20.8 × 12.5 × 6.1 cm (scoop mouth), 5.7 × 4.7 × 4.3 cm (socket)

Weight: 1,275 g

Capacity: 980 ml

Provenance: third century BCE, State of Qin, with later inscriptions from 221 and 209 BCE. Unearthed in September 1982 in Nanyan Village 南晏村, Liquan County 禮泉縣, Shaanxi Province, PRC.

Reference note

Ondřej Škrabal, A Scoop of Filial Piety?

In: Wiebke Beyer, Karin Becker (eds): Artefact of the Month No 7, CSMC, Hamburg,

https://www.csmc.uni-hamburg.de/publications/aom/007-en.html