Jane Austen’s Frugal Art

Kathryn Sutherland

Jane Austen’s manuscript of The Watsons presents something of a mystery. As a working manuscript, it looks different from print. With crossings out and revisions exposed, it requires us to consider how meaning is made. Manuscripts like The Watsons, we sense, are touched by life – quite literally, since they bear the impress of the writer’s hand. Jane Austen’s quirks of spelling, how she formed her letters and how she filled her page are all clues to how she worked and therefore to who she was.

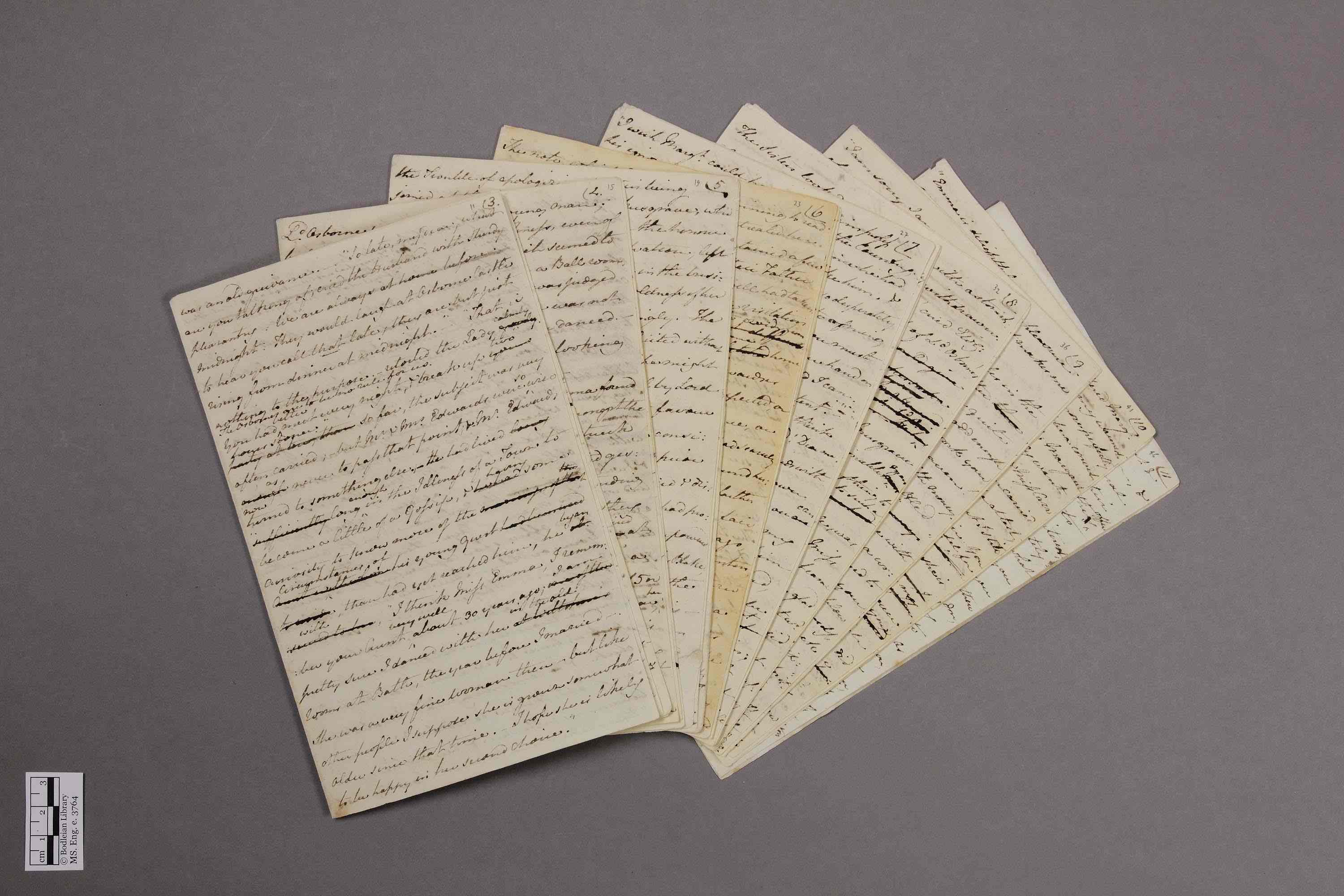

The earliest surviving working draft of a novel by Jane Austen, England’s most celebrated novelist, The Watsons is written into eleven small uncovered booklets of eight pages each (see Fig. 1). At around 17,500 words, it is unfinished and no more than one sixth the length of a regular completed Austen novel. It is a work in progress, with first and second thoughts, deletions and revision, all on display. We literally see the novel growing, from page to page, and from booklet to booklet beneath the writer’s hand. Composition appears to progress confidently, until it breaks off abruptly. It has no title, no chapter divisions and no pagination, though each of its booklets is numbered in the top right-hand corner. Its paper includes the dated watermark ‘1803’, and circumstantial evidence suggests Austen began it in 1804–5 when she was 28 or 29 years old (see Fig. 2). Her nephew and early biographer, James Edward Austen-Leigh, gave it the descriptive title The Watsons from the name of the story’s central family when he published it in 1871, more than fifty years after its author’s death. Enigmatic itself, it is also a rare survival: there is no manuscript evidence for the more famous novels published in Austen’s lifetime. But if we know little about its composition, The Watsons may contain material clues that help unravel a far greater mystery: Austen’s habits as a writer.

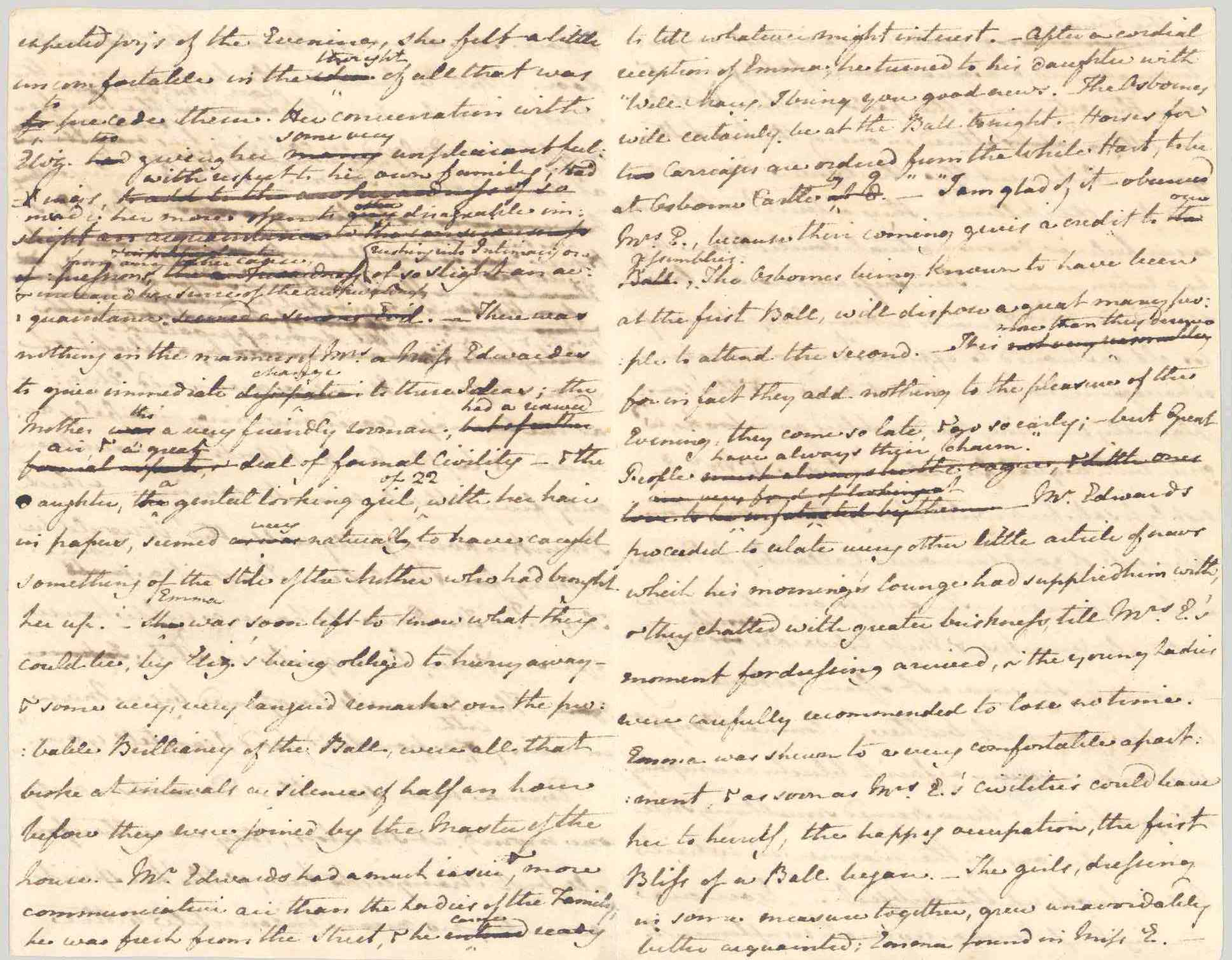

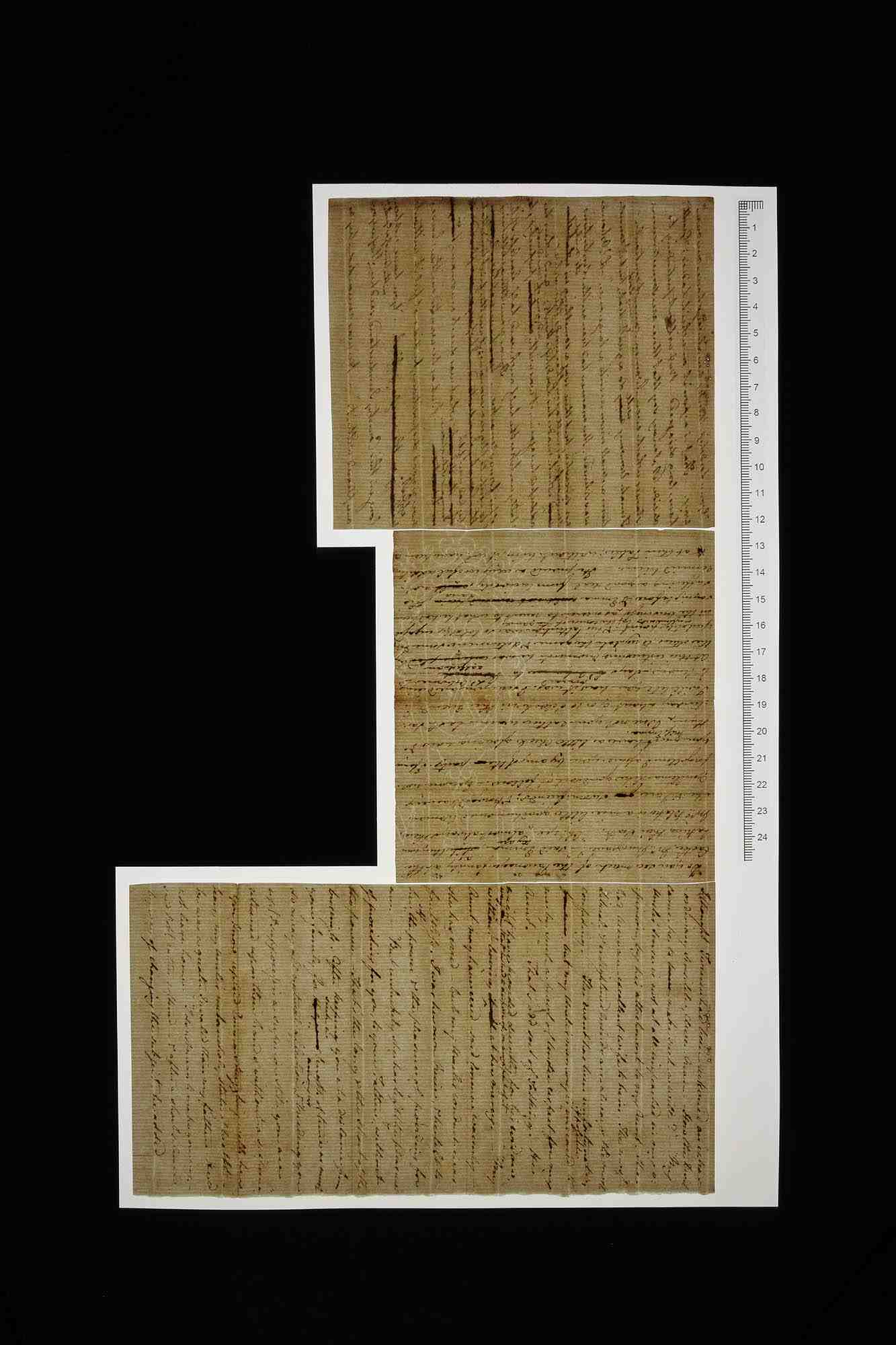

Like most people in the early nineteenth century, Austen wrote with a goose quill pen using iron gall ink. The first thing the reader notices from The Watsons is the controlled penmanship and economy of both the hand and the writing surface: how closely written over its small pages are, every one filled to the very edges, with no margins or white space left for extensive revision or expansion beyond short interlinear insertions (see Fig. 3). The surviving manuscripts of her contemporary novelists in English (those of Frances Burney and Walter Scott, for example) exhibit far more generous deployment of paper, with large tracts of blank space held over for revision and further development.

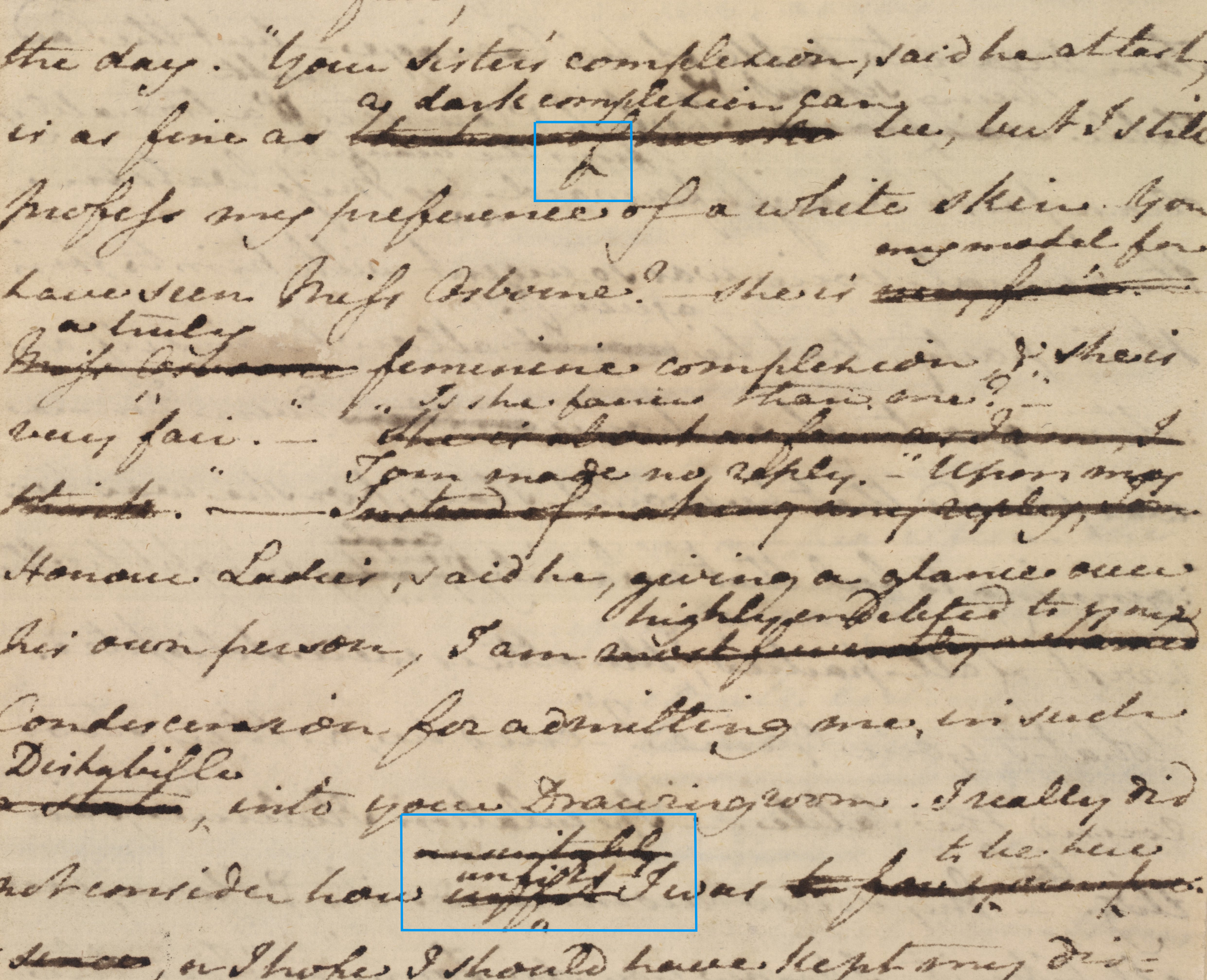

At the local level, too, Austen wrote thriftily, with composition emerging through repetition, or the recycling of first thoughts rather than their expansion. A single word is set down and deleted, another is tested in its place, only for the original to be restored: ‘Postboy’ > ‘Driver’ > ‘Post-Boy’ (Booklet 8, p. 5); ‘unfit’ > ‘unsuitably’ > ‘unfit’ (booklet 10, p. 1, line 12). Tiny obsessive stylistic tics offer mechanical evidence of a similar economy: for instance, where caret insertion marks are regularly formed from unused elements of deleted characters (the tail of an ‘f’ and a ‘y’ and ‘p’ in booklet 10, p. 1, lines 2 and 12) (see Fig. 4).

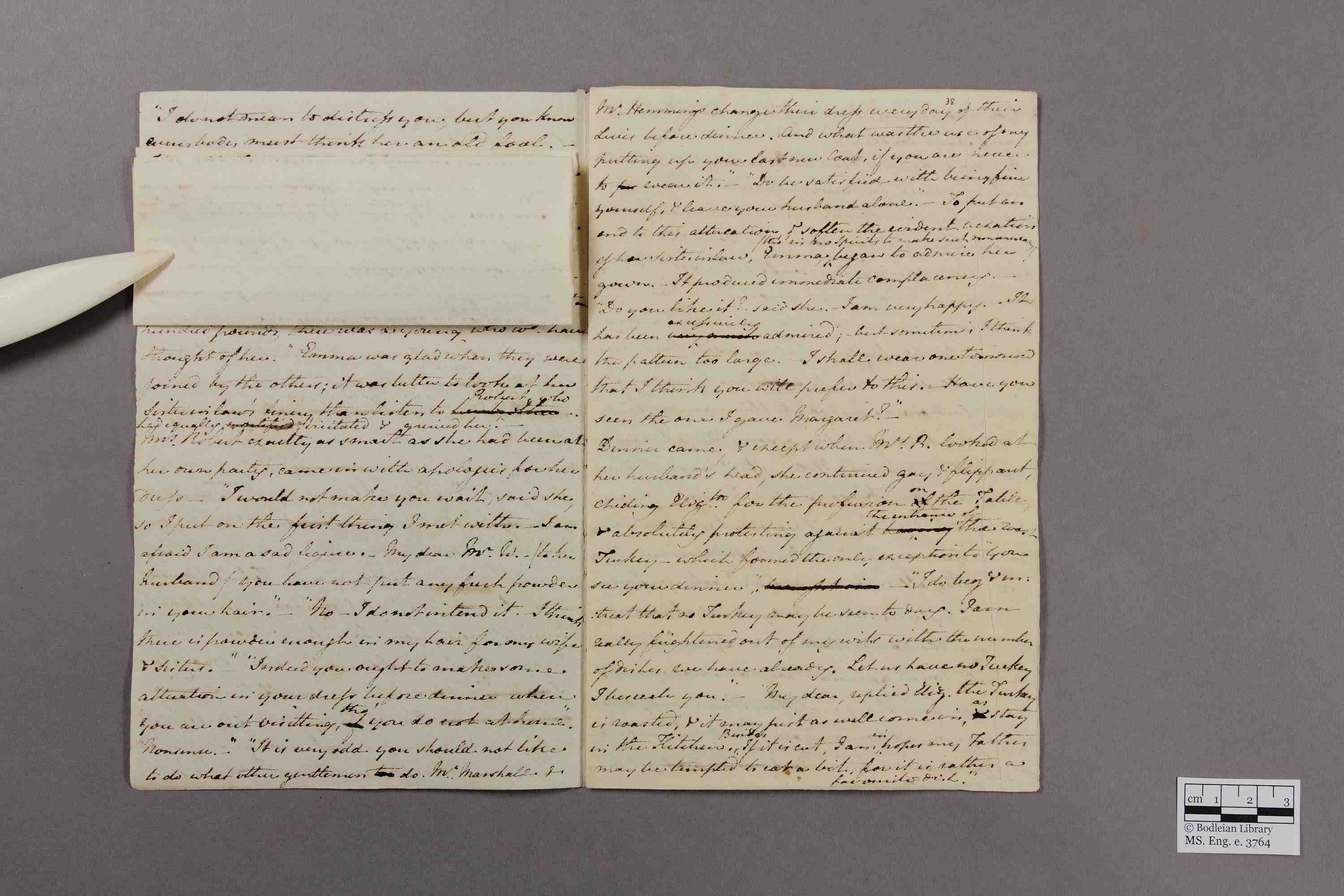

In three places (at booklets 7, p. 7, 9, p. 2, and 10, p. 3) the writing spills over onto separate leaves, which bear the marks of having been carefully patched onto the booklets and held in place with straight steel pins (see Fig. 5). Made from cotton and linen rags, paper of the period was as workable as cloth; sewn and pinned repairs were not unusual. Tailored precisely to the spaces they fill, like patches that mend a shirt or gown, all three show Austen repairing or strengthening her story at three particular points. The first patch replaces a heavily deleted section with new text; the second is a textual insertion expanding the narrative’s backstory; and the third allows Austen to lay down hints for how her story may develop. All three significantly complicate the action.

The eleven booklets are homemade and their pages are small (190 × 120 mm), fashioned by cutting and folding larger sheets of writing paper and nestling their leaves one inside the other, without sewing or binding. Evidence from others of her surviving manuscripts confirms that such small homemade booklets were Austen’s preferred composition surface.

Why might Austen draft directly into little booklets rather than onto single leaves of paper? She had no private room of her own in which to work; little booklets could easily be hidden away from prying eyes. They were portable, too; she could carry them with her with less likelihood of losing single leaves. In size and shape each booklet imitates, gathering by gathering, the appearance of an emerging novel, suggesting that from the earliest moment of putting pen to paper she associated her writing with building a book for publication.

But the booklets, like the style of the revisions, point also to habits of thrift. As a surface for composition, as opposed to copying, booklets impose a high level of discipline upon the writer. They close off options early and leave writing dangerously exposed: get it right first time for there are few opportunities for turning back or reordering the story line. Like the closeness with which she fills each page from the outset, the booklet challenges Austen to keep moving forwards. Drafting onto loose leaves would give far more freedom to discard passages and begin again. Of course, material can be deleted and new matter inserted into the booklets – the three patches in The Watsons show that – but flexibility is limited. There are fewer options for generating new text in an alternative order and sequence.

Students of manuscripts need to be detectives. The regular and repeated disposition of watermarks (the date ‘1803’ and papermaker’s initials ‘WS’) in each booklet of The Watsons reveals that no paper has been removed or wasted: no individual leaves or conjugate leaves (sets of two leaves) have been spoiled. Examination shows, too, that a single sheet of paper was used to cut all three patches. From their changing orientation in relation to the original sheet, these patches, their texts gauged in advance, can only have been inscribed subsequent to cutting (see Fig. 6). Such physical thrift witnesses to remarkable sureness in composition.

The device of patching, like the evidence of local revision, appears to rule out the possibility that Austen wrote her fiction in several separate drafts: The Watsons represents early and late versions compacted into a single material space. Austen used paper sparingly. She wrote during the Napoleonic Wars when paper was expensive and in short supply: cotton and linen cloth were needed to bind wounds.

But her extreme economy may also have served another purpose. Austen described her way of working as – ‘the little bit (two Inches wide) of Ivory on which I work with so fine a Brush, as produces little effect after much labour’ (in a letter of 16 December 1816). This is usually read as explaining the narrow subject matter of her fictions: what she describes elsewhere as ‘3 or 4 Families in a Country Village is the very thing to work on’ (in a letter of 9 September 1814). But it fits even better as a description of her ivory-coloured paper and her method in filling it. The constrained spaces of the little booklets are a material manifestation of her frugal art and an essential discipline for her way of writing.

Why was The Watsons left unfinished? In style, it represents a shift away from the comedy of manners that defines her early novels. Instead, it anticipates the introspection and tougher realism about women’s fate that we associate with her mature novels: with Mansfield Park and Emma. But, as she wrote, its story may have come too close to circumstances in her own life. In 1805 her father died suddenly, leaving Jane, her mother, and sister as financially vulnerable as the family of women described in The Watsons. She may have abandoned the story because its further development became too painful.

Did The Watsons simply run out of fictional steam? Did its story have no real growth left in it? Perhaps that is so. But, as Austen’s most graphically disordered manuscript, it has another story to tell, laying bare the bones of her way of writing more effectively than any other of her surviving drafts.

References

-

Austen-Leigh, James Edward (1871), A Memoir of Jane Austen, to which is added Lady Susan and Fragments of Two Other Unfinished Tales by Miss Austen. 2nd edn, London: Richard Bentley & Son.

-

Le Faye, Deirdre (ed.) (2011), Jane Austen’s Letters. 4th edn, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

-

Sutherland, Kathryn (ed.) (2010), Jane Austen’s Fiction Manuscripts: A Digital Edition. Images and transcriptions of the manuscript can be examined freely here www.janeausten.ac.uk.

Description

The manuscript remained with a branch of the Austen family until the twentieth century. In 1915 it was divided into two portions:

68 pages in the Bodleian Library, Oxford (Bodleian MS Eng. e. 3764)

12 pages in the Morgan Library, New York (Morgan MS MA1034)

All 8 pages of booklet 2 are missing since 2005 and represented only by digital surrogates.

Material: handmade wove and laid paper; 44 leaves + 3 patches

Dimensions: 190 × 120 mm; patches are 121 × 125; 222 × 119; 133 × 121 mm (approximate measurements)

Date: Bath, England, 1804–5

Reference note

Kathryn Sutherland, Jane Austen’s Frugal Art

In: Wiebke Beyer, Karin Becker (eds): Artefact of the Month No 6, CSMC, Hamburg,

https://www.csmc.uni-hamburg.de/publications/aom/006-en.html