All Is Fair in Love (Letters) And War

An Unusual Letter from Ludwig Börne to Jeanette Wohl

Sophia Victoria Krebs

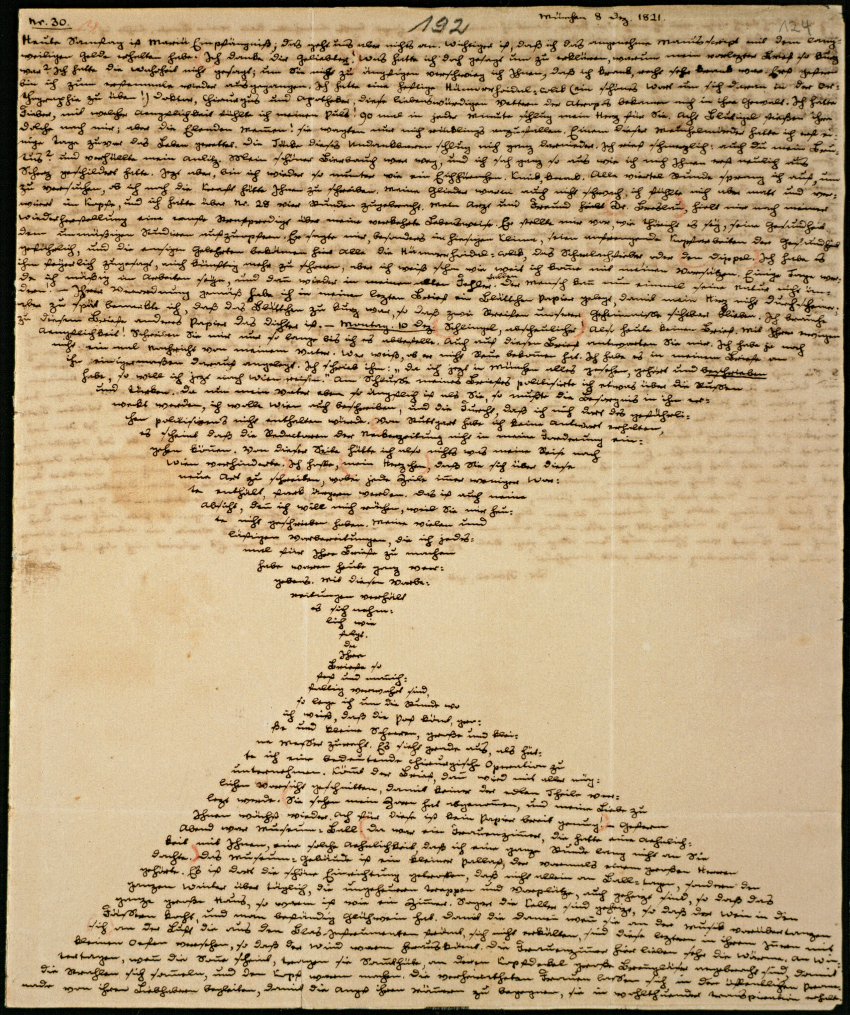

At the age of 35, Börne writes to Jeanette Wohl – once again. The two of them have been good friends for many years; amorous sparks are still flying between them, but, so far, their wedding plans are little more than dreams. Börne writes this letter – beginning on 8 December 1821 and finishing on 10 December – having looked forward to her reply for several days in vain; and the most recent delivery is still not the desired reply. This letter is a perfect example of written communication at the start of the nineteenth century, although Börne uses it to air his frustration in a highly individualized way: He punishes Jeanette Wohl with a very unusual style of letter.

Ludwig Börne, born in 1786 under the name Juda Löw Baruch in Frankfurt’s Judengasse (‘Jew Alley’) is considered to be the first German journalist. His witty, ironic writing style marks him out as one of the trailblazers of the literary Vormärz movement (a literary movement prior to, and leading up to the revolution of 1848) which stood in opposition to the literary and artistic characteristics of the conservative Biedermeier era (the predominant style in Central Europe between the Napoleonic Wars and the revolution of 1848). In 1816, he met Jeanette Wohl, also a Jew from Frankfurt and three years his senior. During the first years of their relationship, its tone oscillated between the familiar and the amorous; in the end, however, the pair developed a deep and productive friendship that can be mapped out in their letters. They communicated frequently for years, and many of their letters were later published.

At the time our letter was written – from 8 to 10 December 1821 – Börne and Wohl have known each other for five years and corresponded for three – but they still address each other with the formal Sie and refer to each other as Dr. Börne and Fräulein Wohl. However, these distance markers amount to no more than coquetry; the remainder of the manuscript paints a very different picture.

Wohl was in Frankfurt, the hometown they shared, while Börne was in Munich. At the time, mail would arrive in Munich twice a week, with delivery days structuring the week. Börne had received Wohl’s most recent letter on 3 December, i.e. five days earlier, and had already responded on 5 and 6 December. Although this letter had not yet been answered, he was impatient enough to start the present letter on Saturday, 8 December, to tell Wohl about some short encounters and an illness he had had. When there was still no letter from Wohl by the following Monday, 10 December, Börne got increasingly irritated:

‘Schlingel, abscheulicher! Also heute keinen Brief‘

(‘Dreadful rascal! Still no letter today’).

Writing a letter in 1820 required more than just the ability to write: the sender also needed some practical skills. Ink had to be mixed, quills had to be skilfully prepared and the paper needed to be just the right size. In addition, many social rules had to be followed in order not to appear rude or uneducated. For example, the higher the recipient’s social standing, the wider the letter’s margins had to be. Placement of the day’s date was also significant: When writing to a distinguished recipient, the writer’s location and the date had to be written on the bottom left of the letter next to the signature; the Kaufmannsdatum (‘merchant’s date’) in the upper right-hand corner was only appropriate when writing to a person of equal or lower standing.

The materials used in the letter also clearly show the close relationship between Börne and Wohl. Börne writes in orderly Kurrent (German cursive), his script is only 2.5 mm high and he forgoes addressing his recipient directly. In the top left-hand corner, he writes his individual letter number which serves both as a reference point for future letters and as a way of checking whether all the letters have indeed reached their recipient. In the top left-hand corner, Börne has written his location and the date (to the left there is an archive note in pencil). He opens with:

‘Heute Samstag ist Mariä Empfängnis; das geht uns aber nichts an’

(‘Today, Saturday, is the Solemnity of the Immaculate Conception, but that doesn’t concern us’).

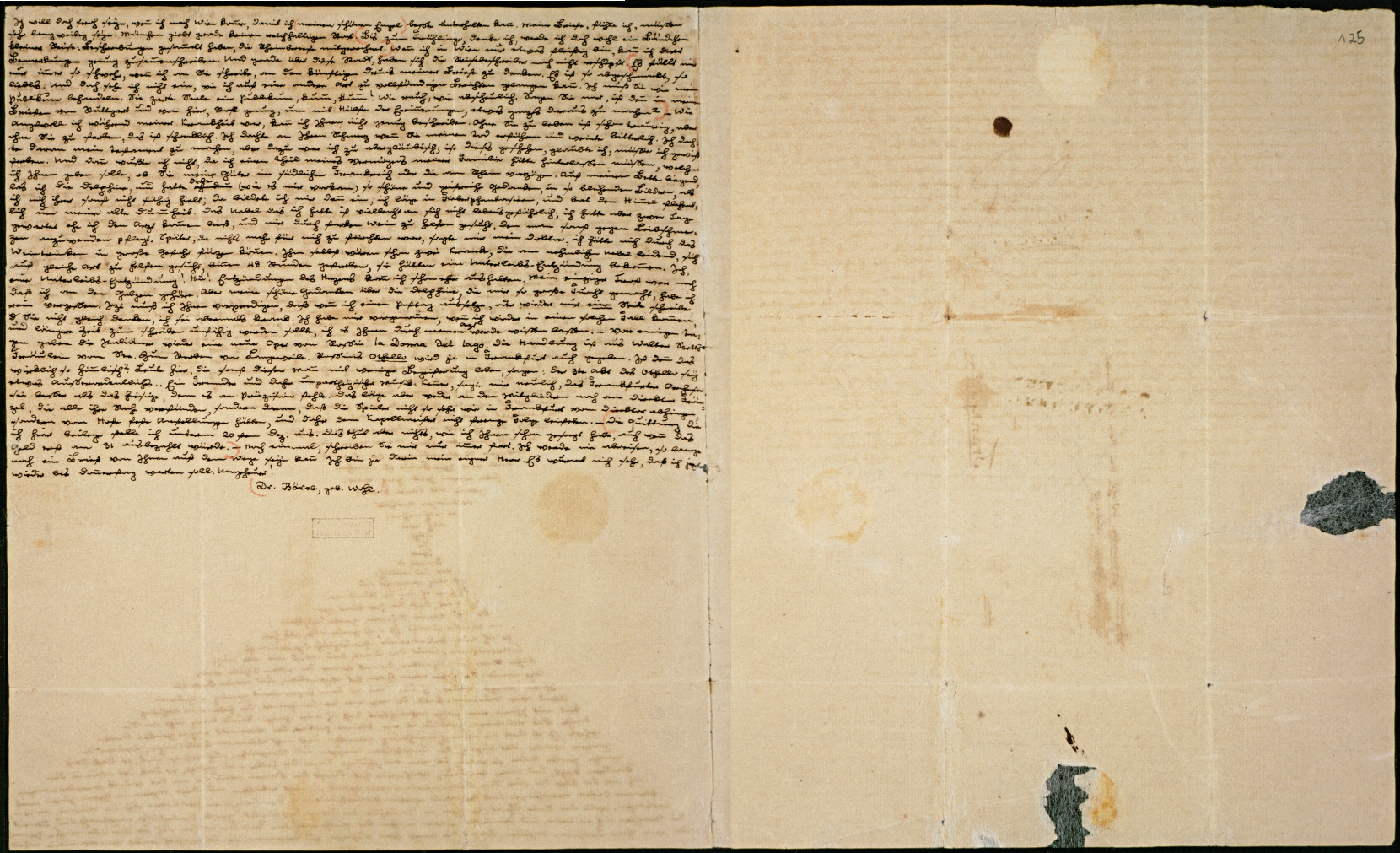

He leaves almost no margins at the top or to the left and right of his writing, as the so-called Respektraum (‘respect space’) is unnecessary in this case. His signature at the end of the letter also comes very close to the body of the text, i.e. there is no indication of any material or social distance between the sender and the recipient (see Fig. 2). Börne signs his letter ‘Dr. Börne, geb. Wohl’ (‘Dr. Börne, né Wohl’), gently teasing Wohl and alluding to their close relationship.

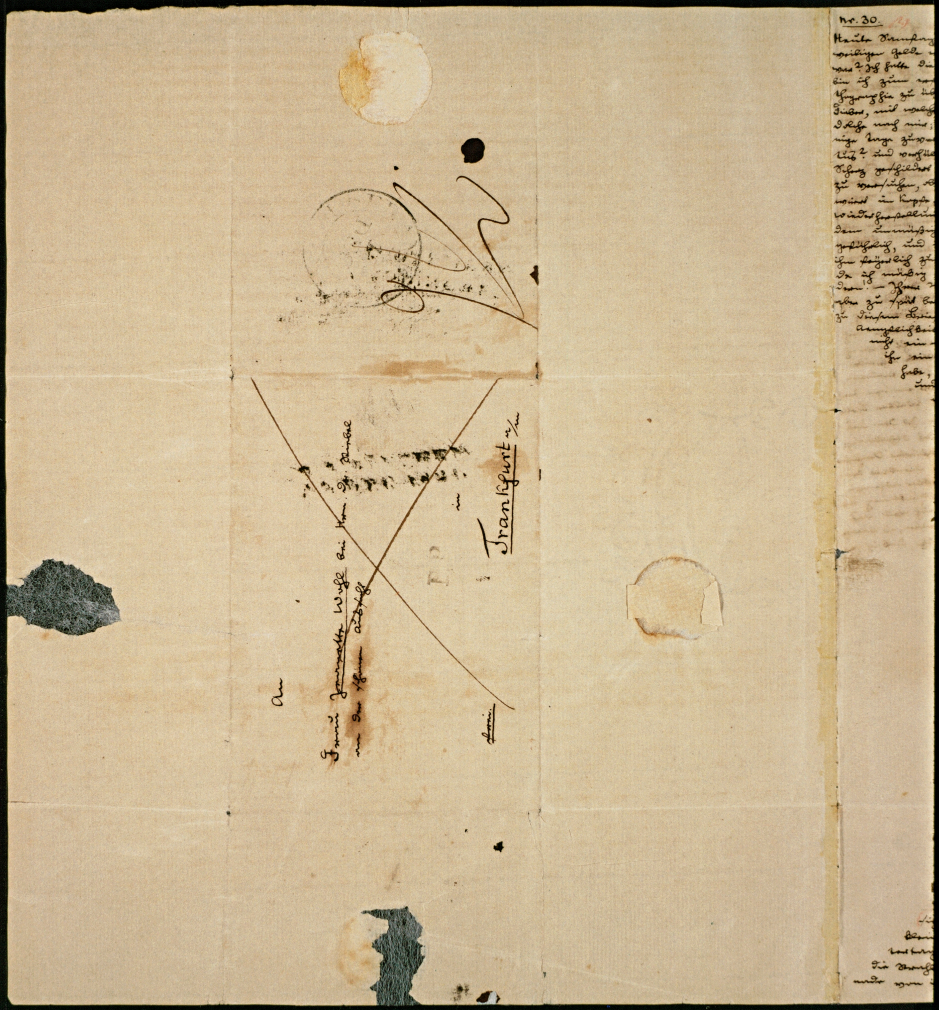

For his letter, Börne uses a large sheet of paper which is then folded, creating four pages to be used in different ways. At the time of his writing, the way in which a letter was wrapped was also an indicator of the relationship between the sender and the recipient. The sender could choose to make their own envelope – ready-made envelopes would only become widely available roughly 40 years later – or to use the so-called parcel fold, as Börne did in our example. Using a parcel fold, as we can see from Börne’s letter, leaves the first three pages for the letter itself (although Börne only uses two), while the last page must remain empty to create the outside of the letter after folding the sheet. In effect, the letter is wrapped in itself, i.e. in the empty fourth page; it is then closed and sealed. If the sender and the recipient were close, as Börne and Wohl were, using this paper-saving method was acceptable.

The letter is addressed as follows: ‘An Frau Jeanette Wohl bei Hrn. Dr. Stiebel an der schönen Aussicht in Frankfurt a/m’ (see Fig. 3). Börne does not give a sender’s address, as this would only become the norm in the mid-nineteenth century; prior to that, the recipient would usually know the sender from the seal and the handwriting. Also noted on the address page are postal and tax references. In the bottom left-hand corner, Börne wrote ‘frei’, (‘free’), indicating that the letter was paid for in full (which the post office confirmed with a stamp saying ‘P.P.’ for ‘Porto Payé’). Crossing out the address would have been done at the post office, showing an ‘X’ lying on its side – another indication that all fees were fully paid, and that the recipient would not need to pay any additional fees. On the right, we can make out the upside-down tax notation ‘2/16’ added by the post office, where the first number refers to the Bavarian tax and the second number indicates the follow-on fee.

Parcel-folding a letter makes it lighter and cheaper. However, there was the constant danger of damaging the letter while opening it, especially the third page which made up the back of the envelope. If, like Börne, one was writing to a socially close person and left little or no margins, breaking the seal would create unavoidable seal tears, such as the ones seen on the third page of our letter (Fig. 2). Thus, any text on the backside of the seals was often lost due to its adhering to the seal wax or – as in this case – the seal wafer (an alternative means of sealing letters, made from dough). To avoid tearing the letter or at least minimizing the damage of the seal tear, it was helpful to open letters using knives and scissors – as Börne describes in his letter:

‘Da Ihre Briefe so fest und mannichfaltig verwahrt sind, so lege ich um die Stunde wo ich weiß, daß die Post kömt, große und kleine Scheeren, große und kleine Messer zurecht. Es sieht gerade aus, als hätte ich eine bedeutende chirurgische Operation zu unternehmen. Kömmt der Brief, dann wird mit aller möglichen Vorsicht geschnitten, damit keiner der edlen Theile verletzt werde.’

(‘As your letters are kept so closely and in such great numbers, I shall prepare large and small scissors, large and small knives, for the hour when I know the mail will arrive. It looks as though I was about to undertake a major surgical operation. Once the letter arrives, it is then cut using all possible precaution, so as not to injure any of its noble parts.’)

However, this amounts to love’s labour’s lost: no letter had arrived.

To vent his vexation with his unnecessary preparations, Börne uses highly unusual spacing for his letter. Starting with the second third of the first page, the breadth of his script narrows from line to line, until there is only one word left in the middle of the line. Only then will he widen his lines again, resulting in the peculiar hourglass shape of the text on the first page (see Fig. 1). He comments on this form, telling Wohl:

‘Ich hoffe, mein Herzchen, daß Sie sich über diese neue Art zu schreiben, wobei jede Zeile immer weniger Worte enthält, stark ärgern werden. Das ist auch meine Absicht, denn ich will mich rächen, weil Sie mir heute nicht geschrieben haben.’

(‘I hope, dear heart, that this new way of writing, where each line contains fewer words, will irritate you greatly. This is my intention, as I would like to take my revenge on you for not having written to me today.’).

In the lower part of the letter, where each line increases again, Börne gradually calms down and remembers the affection he has for Wohl:

‘Sie sehen mein Zorn hat abgenommen, und meine Liebe zu Ihnen wächst wieder. Ach für diese ist kein Papier breit genug!’

(‘As you can see, my wrath has abated and my love for you grows again. Alas, no sheet of paper will be wide enough for it!’)

In her response, which arrived only four days later, Wohl does not deign to comment on the letter’s creative, playful form; she simply writes to her friend who was recently ill:

‘Ich bin beruhigt durch Ihren scherzhaften Brief, der die Farbe der Gesundheit trägt [...]’

(‘I am relieved by your light-hearted letter, coloured as it is by your good health […]’).

Video

References

- Heuer, Renate and Andreas Schulz (eds) (2012), Ludwig Börne – Jeanette Wohl. Briefwechsel (1818–1824). Edition und Kommentar, Berlin/Boston: Walter de Gruyter, 328–332 (= Nr. 82).

- Jaspers, Willi (1989), Keinem Vaterland geboren. Ludwig Börne. Eine Biographie, Hamburg: Hoffmann und Campe.

- Nachgelassene Schriften von Ludwig Börne. Herausgegeben von den Erben des literarischen Nachlasses. Bd. 2: Briefe und vermischte Aufsätze. Aus den Jahren 1819, 1820, 1821, 1822, Mannheim: Friedrich Basserman, 1844, 33–42 (= Nr. 35).

- Rippmann, Inge and Peter (eds) (1977), Ludwig Börne – Sämtliche Schriften, Bd. IV, Dreieich: Melzer, 486–492 (= Nr. 57).

Description

Universitätsbibliothek Johann Christian Senckenberg, Frankfurt am Main.

Shelfmark: Nachl.L.Börne BVIII, Nr. 192, Bl. 124-125.

Material: Double sheet of laid paper, folded, with one blank and three written pages, one of them showing an address, iron gall ink, script size approx. 2.5 mm. Subsequent notations in red and black pencil. Parcel fold sealed with white wafer (embossed ‘D B’), dimensions of the folded envelope: 7.7 × 10.6 cm.

Dimensions: 41.6 (= 20.8 + 20.8) × 24.8 cm

Provenance: Munich, 08/12 and 10/12/1821

Post marks: Cancellation stamp: bulls-eye stamp with Elzevir font ‘FRANKFURT’, inscribed ‘10 D E C’; ‘P.P.’ stamp (‘P. P’ meaning ‘Porto payé’, i.e. ‘Postage paid’)

Reference note

Sophia Victoria Krebs, All Is Fair in Love (Letters) And War – An Unusual Letter from Ludwig Börne to Jeanette Wohl

In: Wiebke Beyer, Karin Becker (eds): Artefact of the Month No 3, CSMC, Hamburg,

https://www.csmc.uni-hamburg.de/publications/aom/003-en.html