Efficacy is in the prayer, not in the image. Or vice versa?

Sabiha Göloğlu

An eighteenth-century Ottoman prayer book in the Ankara Ethnography Museum consists of an extraordinary selection of religious images including seal designs, footprints of the Prophet Muhammad, eschatological compositions, and depictions of the holy quartet of cities: Mecca, Medina, Jerusalem, and Damascus. The signs of use and detailed marginal notes accompanying these devotional images reveal how users sought cure, protection, and intercession from this manuscript. Such internal evidence raises questions: What was special about the content of this prayer book? How did religious imagery function, and in what ways was it deemed efficacious?

This pocket-size manuscript (16.6 × 11 cm) consists of 128 folios and is bound in dark red leather. It contains excerpts from the Qurʾan, other religious texts, and marginal notes in Arabic and Turkish written in naskh script, the most widespread book hand in the eastern part of the Islamic World. The manuscript was written by one hand and consists of two sections, separated by four blank pages (fols 90b–92a). While the first part is mainly composed of writing, the second part is richly illustrated and illuminated with gold, silver, and opaque watercolours. Only at a later point in time were the four blank pages filled with a prayer and with a description of its virtues. These were written by a different hand, just like several other notes at the beginning and the end of the manuscript (fols 1a–1b and 119a–128b), which were added by various users.

We do not know the exact date this prayer book was made, but some notes provide clues. The additional prayer on fol. 91b ends with the year AH 1164/1750–51 CE, which helps us date the manuscript to the first half of the eighteenth century. A second note on fol. 122b records the enthronement of the Ottoman Sultan Selim III on AH 11 Rajab 1203/7 April 1789 CE. Noting such important events in manuscripts was a common practice.

The first section of the manuscript (fols 2b–90a) is plainly decorated: the text is framed in gold- and black-ruled lines and has a wide margin. The beginnings/endings of the suras and the verse dividers are illuminated in gold. The text is composed of a selection of excerpts from the Qurʾan, starting with the first sura al-Fātiḥa and the sixth sura al-Anʿām, followed by two religious texts in Arabic: the ‘Most Beautiful Names of God’ (Esmāʾ-i Ḥüsnā) and the ‘Prophet Muhammad’s Physical Description’ (Hilye-i Şerīf). Similar prayer books with suras, prayers, and/or images were known as Enʿām-ı Şerīf in the Ottoman Empire, which is the Turkish title derived from the often included sura al-Anʿām (‘The Cattle’). Such prayer books were widely produced in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. They were frequently illustrated and with varying contents.

The second section consists of lavishly decorated texts and religious images (fols 92b–118b). The latter are usually accompanied by texts like Turkish poems, Arabic formulas, and Qurʾanic excerpts, which are integrated into the design and/or added in the margins. In several cases, additional contemporary notes in either the margins or the ruled areas describe the miraculous effects of the images and texts and explain their use. For example, those who write or read the ‘Prophet Muhammad’s Physical Description’ (which is repeated in Turkish in the second part of the manuscript, fols 92b–93a) will be blessed as if they had seen the Prophet and will not suffer in their graves. Those who gaze in the morning or the evening at the ‘Seal of Prophethood’ (Mühr-i Nübüvvet), a richly ornamented design representing the mark of prophethood between Muhammad’s shoulders, will be protected from troubles and accidents.

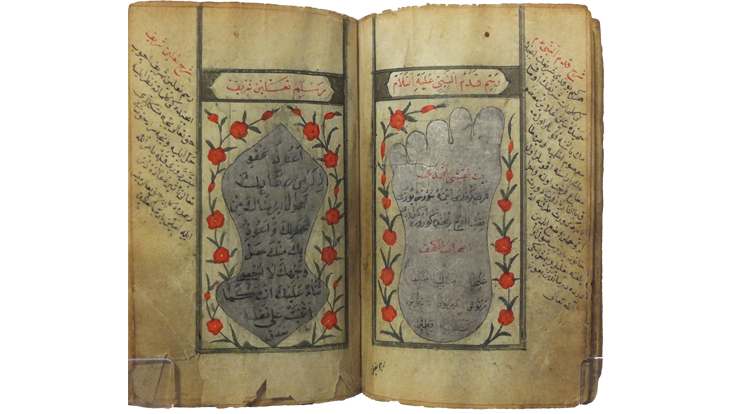

On a double page, the footprint and the sandal of the Prophet are depicted with accompanying marginal notes. Two texts known for their talismanic use are written on the image of the footprint: a Turkish couplet about touching the footprint with one’s own face, together with the names of the Seven Sleepers (referring to a legend about seven faithful young men). The marginal note next to the footprint encourages the user to read or write these texts on a separate sheet of paper for several purposes, such as boosting the sale of goods, comforting innocents, and aiding the pregnancy of women (Fig. 1, right). Another text is written on the sandal of the Prophet; this is an altered version of a saying attributed to the Prophet Muhammad (Hadith) about seeking refuge in God. It is emphasized as particularly virtuous by the following line in the margin (Fig. 1, left): ‘Efficacy is in the prayer, not in the image’. The marginal note also states that the text inscribed on the sandal makes wishes come true and eases difficulties.

The text in the upper part of both images appears to have been rewritten by a different hand and ink, rendering it hard to decipher (Fig. 1). This restoration was probably necessary after abrasive devotional engagement with both images. The users’ engagement evidently transcended mere gazing at, reading, redrawing, and rewriting the texts and images. Instead, they seem to have sought power by kissing, touching, or rubbing the images and words, which eventually resulted in pigment loss on the silver surfaces. Thus, protective roles were attributed not only to the textual contents but also to their visual representations. Such practices seem to contradict what is implied by the marginal note next to the sandal: ’Efficacy is in the prayer, not in the image’.

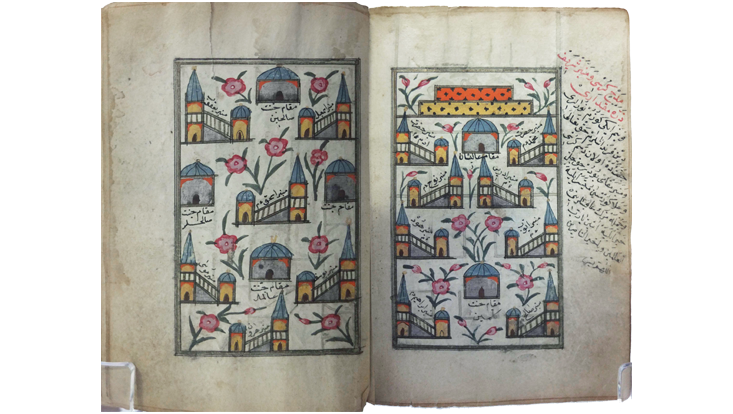

Besides seal designs and prophetic footprints, the manuscript contains a rich collection of eschatological imagery including representations of the Day of Judgement, heaven, and hell with the ‘Lote Tree of the Limit’ (Sidretü’l-Müntehā), the ‘Frequented Houses’ (Beytü’l-Maʿmūr), and other details. A double-page composition depicts the pulpits of the prophets and the tombs of the religious scholars and the pious, with a marginal note expressing the wish to reach these places in the afterlife (Fig. 2). On the Day of Judgement, Muhammad, the other prophets and the religious scholars are believed to intercede with God on behalf of believers, which might explain why images of their pedestals and pulpits were included in this prayer book.

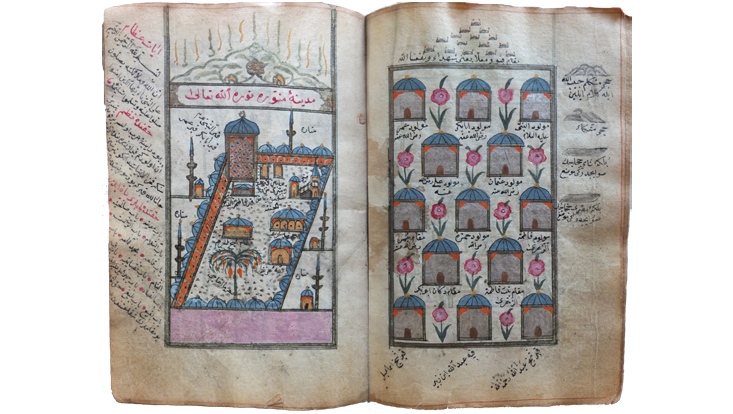

Towards the end of the manuscript (fols 110a–113a), Mecca, Medina, Jerusalem, and Damascus are featured in single-page paintings with abundant marginalia. The sanctity of prayers performed in these four holy cities ranks highest according to a Hadith. In Fig. 3 (left), the Mosque of the Prophet (al-Masjid al-Nabawi) in Medina is accompanied by three marginal notes: a verse from sura al-Aḥzāb about God’s blessings of the Prophet, a list of the gate names of the holy mosque and city, and a Turkish poem about the salvation that may be granted by touching the Prophet’s tomb with one’s face. The latter confirms that depictions of the holy sites could be kissed and touched for blessings, cure, protection, and intercession.

Furthermore, the pages between the images of the holy cities are filled with polychrome paintings of domed buildings and flowers in the ruled areas, and monochrome drawings of various structures in the margins (Fig. 3, right). They depict a variety of buildings and sites in and around the holy cities, such as the birthplace of the Prophet and the Muʿallā cemetery (Jannat al-Muʿallā) in Mecca, as well as Mount Uhud and the Mosque of Hamza near Medina. In addition to their talismanic purposes, representations of these sites could also have served as visual aids for physical or virtual pilgrimage.

Overall, the rich array of religious images in this prayer book was carefully selected to meet its users’ needs for healing, protection, and intercession, to ease problems and fulfil wishes, confirmed by the extensive marginalia and signs of use. The diverse textual and visual contents of the manuscript provided its users with a range of talismanic templates for different forms of devotional engagement from reading to gazing, and from touching to kissing.

References

- Bain, Alexandra (2001), ‘The Enʿam-ı Şerif: Sacred Text and Images in a Late Ottoman Prayer Book’, Archivum Ottomanicum 19, 213–238.

- Flood, Finbarr Barry (2014), ‘Bodies and Becoming: Mimesis, Mediation, and the Ingestion of the Sacred in Christianity and Islam’, in Sally M. Promey (ed.), Sensational Religion: Sensory Cultures in Material Practice, New Haven: Yale University Press, 459–493.

- Göloğlu, Sabiha (2018), ‘Depicting the Islamic Pilgrimage Sites: Mecca, Medina, and Jerusalem in Late Ottoman Illustrated Prayer Books’, in Michele Bernardini, Alessandro Taddei and Michael Douglas Sheridan (eds), Proceedings of the 15th International Congress of Turkish Art, Ankara: Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism, 323–338.

- Gruber, Christiane (2018), The Praiseworthy One: The Prophet Muhammad in Islamic Texts and Images, Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Khamehyar, Ahmad (2016), ‘Osmanlı Dönemi Resimli Dua Kitaplarında Kutsal Emanetlerin Tasvirleri’, in Nicole Kançal-Ferrari and Ayşe Taşkent (eds), Tasvir: Teori ve Pratik Arasında İslam Görsel Kültürü, Istanbul: Klasik, 389–420.

- Kister, Meir Jacob (1996), ‘Sanctity Joint and Divided: On Holy Places in the Islamic Tradition’, Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 20, 18–65.

- Perk, Haluk (2010), Osmanlı Tılsım Mühürleri: Haluk Perk Koleksiyonu, Istanbul: Haluk Perk Müzesi Yayınları.

- Porter, Venetia (2007), ‘Amulets Inscribed with the Names of the ‘Seven Sleepers’ of Ephesus in the British Museum’, in Fahmida Suleman (ed.), Word of God, Art of Man: The Qur’an and Its Creative Expressions, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 123–134.

- Taşkale, Faruk and Hüseyin Gündüz (2006), Hilye-i Şerīfe in Calligraphic Art: Characteristics of the Prophet Muhammed, Istanbul: Artam Antik A.Ş. Kültür Yayınları.

Description

Location: Ankara Ethnography Museum (Ankara Etnografya Müzesi), Turkey

Shelfmark: 17069

Material: 128 folios of cream-coloured, thick, polished paper with watermarks, black, red, and white naskh script in Arabic and Turkish, 9 lines per page; dark red leather binding with flap, recessed cream-colored central medallions, corner pieces, and borders

Dimensions: 16.6 × 11 cm

Provenance: twelfth c. AH / eighteenth c. CE, Ottoman Empire

Reference note

Sabiha Göloğlu, 'Efficacy is in the prayer, not in the image. Or vice versa?'

In: Wiebke Beyer, Karin Becker (eds): Artefact of the Month No 2, CSMC, Hamburg,

https://www.csmc.uni-hamburg.de/publications/aom/002-en.html