Almost a Happy End for a Broken Clay Tablet

Cécile Michel and Wiebke Beyer

Clay tablets from the Ancient Near East inscribed in cuneiform, the oldest known writing in the world, were – and, indeed, still are – often excavated illicitly and then sold on the black market. Even worse, fragments of tablets were sold to countless international collectors without much hope of the pieces ever being re-assembled again. Consequently, many of the written stories on such tablets – regardless of whether they are myths, letters or witnessed reports – no longer have an ending (or even a beginning, for that matter). The situation is quite different for two particular fragments, however: KUG 15 and AO 29196. Thirty years ago, in the 1980s, a young Assyriologist working in the Louvre realised that the counterpart of the fragment she was working on was not in the Louvre or in Paris, or even in France, but in another country…

In the 1920s, the Gießener Hochschulgesellschaft (Giessen University Society) in Germany acquired more than fifty clay tablets, including the fragment of a tablet that came to be known as KUG 15. Several decades later, in 1982, the private collection of the Assyriologist Marguerite Rutten was donated to the Louvre in Paris. This contained a total of 137 inscribed fragments of clay tablets. One of these fragments – AO 29196 – is the lower edge of a tablet.

The young French researcher just described is now a professor at the University of Hamburg and Research Director at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique in Nanterre, France: Cécile Michel. More than thirty years ago, she noticed that fragment AO 29196 did not have a counterpart in the same collection at the Louvre, but in one in Germany – at the University of Giessen, where it is referred to as KUG 15. While the University’s clay-tablet collection is rather small and thus relatively easy to manage, the Louvre preserves more than 12,000 cuneiform artefacts within its walls. How did Cécile Michel happen to discover this specific fragment, then?

Michel: While I was completing my Master’s degree in Assyriology in spring 1985, I asked my supervisor, Professor Paul Garelli, if it would be possible to work on real tablets preserved in the Louvre Museum and not just on printed cuneiform copies. During the autumn, I started a PhD on an Assyrian merchant who had kept an archive of tablets that I tried to reconstruct. Some of these tablets were preserved in the Louvre, so I started going there every week, collating texts. I had found out that a ‘lost’ private collection of thirty tablets belonging to Georges Contenau had actually been given to the Louvre in the mid-1920s while he was curator of the Department. While I was preparing a new edition of these texts, I was told that there were still two groups of unpublished Old Assyrian tablets in the collection, [one of them from M. Rutten’s collection; editor’s note], and the curator entrusted these tablets and fragments to me for publication.

Common tools such as laptops, and the internet were not yet accessible at that time. So how exactly did a researcher study cuneiform tablets in a museum at that early stage?

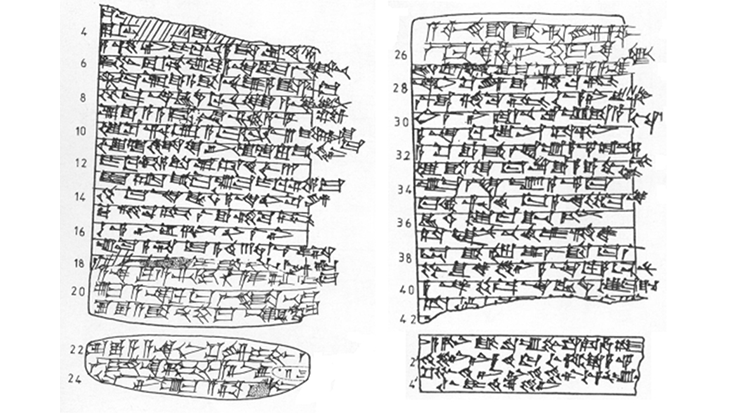

Michel: When I did my research work at the Louvre, I sat in a curator’s office at a table near a window overlooking the Seine. The light was excellent. I deciphered the texts, working with pen and paper, writing down the transliteration of signs line by line and at the same time drawing a copy of the tablet, taking its shape and broken parts into account, and trying to reproduce the cuneiform signs as accurately as possible, including the spacing of the lines and the relative positions of the signs. I built up files of handwritten cards ordered tablet by tablet, by proper and geographical names, by words and so on. I typed the basic transliterations with a typewriter, but had to add the diacritics by hand. My publication of all these tablets filled an entire issue of the Revue d’Assyriologie in 1987.

The texts on the two broken tablets, AO 29196 and KUG 15, are written in cuneiform script and formulated in the Old Assyrian dialect, which was used in the first half of the second millennium BC. They are part of a witnessed record of a meeting attended by two parties and a legal adviser. Texts of this kind are not uncommon in the corpus of texts created by a merchant society. How did you realise that the two fragments belong to the same tablet?

Michel: This text is a sworn testimony linked to a dispute between two merchants, Sue’a and Ennum-Aššur, concerning 40 minas (20 kilos) of silver. The Louvre fragment only has eight readable lines on it, which were meant to come at the bottom of the tablet; it represented the end of the obverse, the lower edge and the very beginning of the reverse. I was able to read the name of one of the protagonists on these lines – Sue’a – and the important amount of 40 minas of silver that was disputed. I searched through the published volumes on Assyriology to see if I could find anything about this man and discovered that the matter had actually been reported on a dozen tablets. The dossier was first gathered and studied by J. Lewy and G. Eisser in 1935, but the Giessen tablet was only shown as a transliteration there without any illustrations or photographs of it. It was impossible to understand or even guess anything from the transliteration. But fortunately, a picture of the tablet was published in 1966, this time by the German researcher Karl Hecker. I had already copied the Louvre fragment and noted its dimensions before I saw that, so I checked to see if my own cuneiform copy matched the copy of the Giessen tablet that Hecker had drawn. Since he had also indicated the dimensions of this fragment – which was rare in the publications at that time – I was able to reduce both copies to the same scale, and bingo, they matched perfectly; the copies were so faithful to the original that they could be joined together easily.

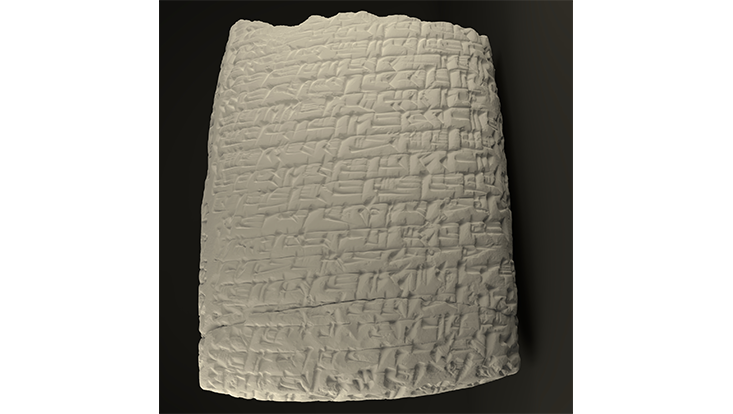

Nowadays, there are completely different technologies and ways of joining such fragments together. CSMC owns portable 3D scanners, so together with a 3D data engineer and a research assistant, Cécile Michel travelled to the two locations to make 3D scans of both fragments. The scanner they used is a high-resolution 3D device which employs structured light to project a pattern of parallel light forming a stripe on the surface of the artefact. The dents in the surface and the elevations on it yield the light pattern and their height information also gets encoded. The displaced light pattern is then captured by the cameras inside the device and used to produce a 3D reconstruction of the surface. The breaking edges of the two clay fragments are very even, so not much substance was lost. They fit together very well and prove Cécile Michel’s statement.

In the text the lawyer, who was sent from the capital Aššur, makes the accusation that another merchant has deposited a large amount of silver at Ennam-Aššur’s house. The defendant starts to answer, complaining about the repeated interrogation on the matter – and then the text stops all of a sudden. The upper edge of another part of the tablet is missing, too. The broken-off edges of this part are just as even as the lower edge. What happened to the third fragment of the tablet?

Michel: One piece is, indeed, missing. I believe this tablet was artificially cut off at the top and lower parts, presumably to get more money from the sale of the three fragments. According to my reconstruction, the missing top part could be about the size of the Louvre fragment and contain eight or nine lines of writing. I haven’t been able to identify it yet, but I do have an idea about the content of the three first lines. It’s probably in a collection somewhere. The main problem for us is that, for many collections, only whole tablets that are well preserved have been photographed and published; fragments of tablets have often been ignored. This is probably the case for the lost fragment as well.

References

- Hecker, Karl (1966): Die Keilschrifttexte der Universitätsbibliothek Giessen. Berichte und Arbeiten aus der Universitätbibliothek und dem Universitätsarchiv Giessen 9, Giessen.

- Michel, Cécile (1987): ‘Nouvelles tablettes Cappadociennes du Louvre’, Revue d’assyriologie et d’archéologie orientale 81, 3–78.

- 3D Scans of both fragements in the UHH Research data repository: KUG 15 (doi: 10.25592/uhhfdm.766) and AO 29196 (doi: 10.25592/uhhfdm.918).

Description

Location: KUG 15: University Library, Giessen, Germany; AO 29196: the Louvre, France

Material: clay

Form: tablet (fragments)

Provenance: Kaneš (Kültepe, Central Anatolia, Turkey)

Reference note

Cécile Michel, Wiebke Beyer, 'Almost a Happy End for a Broken Clay Tablet'

In: Wiebke Beyer, Karin Becker (eds): Artefact of the Month No 1, CSMC, Hamburg,

https://www.csmc.uni-hamburg.de/publications/aom/001-en.html