‘Signatures of Friendship’ at the CSMCThe Second Digital Life of a Guestbook

20 January 2025

The Jerusalem guestbook of Miryam and Moshe Ya’akov Ben-Gavriêl is a small object of only 200 pages – yet it opens doors to more stories than a single researcher can uncover. Sebastian Schirrmeister wants to use new digital techniques to explore this microcosm and link it to larger bodies of knowledge.

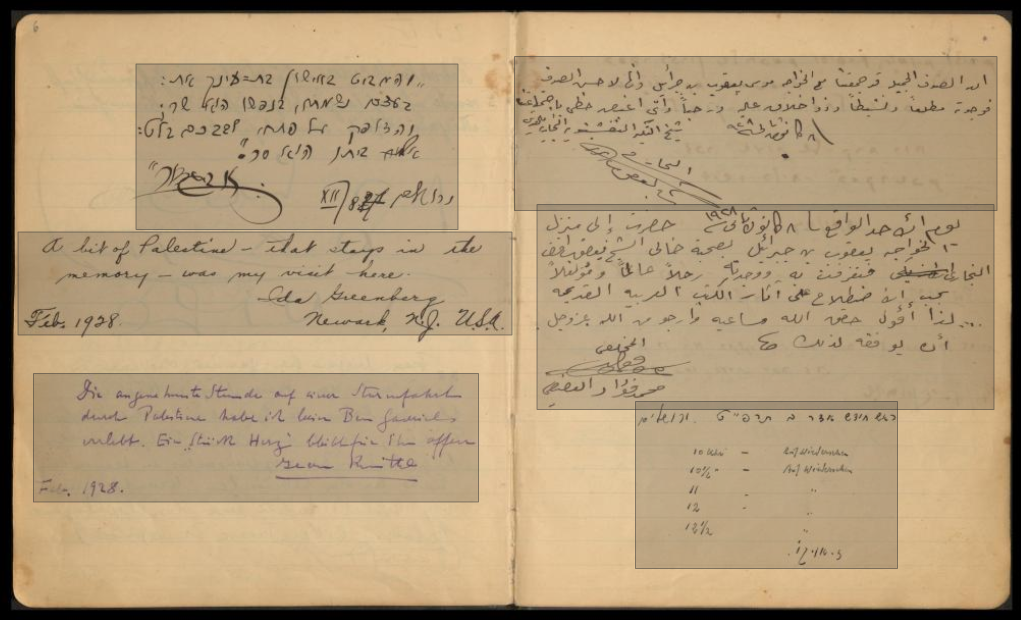

In March 1939, the German writer and critic Max Brod, editor of the works of Franz Kafka and his closest friend, fled from the Nazis to Palestine. Having just arrived in Jerusalem, one of his first stops was the house of Miryam and Moshe Ya’akov Ben-Gavriêl. On 23 March, he signed their guestbook, in Hebrew script, which the couple had been keeping since their own arrival in Jerusalem twelve years earlier. In those years, the guestbook was filled with entries from German-Jewish intellectuals who had to find a new home away from Europe and for whom the Ben-Gavriêls’ house was one of the first ports of call for settling in the foreign environment.

In March 1939, the German writer and critic Max Brod, editor of the works of Franz Kafka and his closest friend, fled from the Nazis to Palestine. Having just arrived in Jerusalem, one of his first stops was the house of Miryam and Moshe Ya’akov Ben-Gavriêl. On 23 March, he signed their guestbook, in Hebrew script, which the couple had been keeping since their own arrival in Jerusalem twelve years earlier. In those years, the guestbook was filled with entries from German-Jewish intellectuals who had to find a new home away from Europe and for whom the Ben-Gavriêls’ house was one of the first ports of call for settling in the foreign environment.

By 1966, a year after the death of Moshe Ya’akov Ben-Gavriêl, more than 600 people had written a total of 1,200 entries in the guestbook, including such well-known figures as Arnold Zweig, Gabriele Tergit, and Oskar Kokoschka. They left thoughts, poems, drawings, and, much more often, simple expressions of gratitude or just their names, like Max Brod. She an actress, he a writer and journalist, the Ben-Gavriêls turned their Jerusalem home into a salon where friends, colleagues, and new acquaintances from all over the world met. Over the course of four decades, their guestbook became a multilingual smorgasbord of notes from famous and unknown people, and a reflection of the eventful times in which it was created. For example, while dozens of guests signed the pages every year in the mid-1930s, many of them having just fled Europe, there are only two entries for the whole of 1948: It was the year of the first Jewish-Arab war, the siege of Jerusalem, and the establishment of the State of Israel.

The guestbook ended up in the archive of Moshe Ya’akov Ben-Gavriêl, which is held at the National Library of Israel (NLI). His estate is one of 24 similar archives by German-Jewish intellectuals that the NLI and the CSMC have jointly digitised between 2020 and 2024. Involved in this project was the literary scholar Sebastian Schirrmeister, who had already come across the Ben-Gavriêls’ guestbook in the archive several years earlier while doing research for his doctoral thesis.

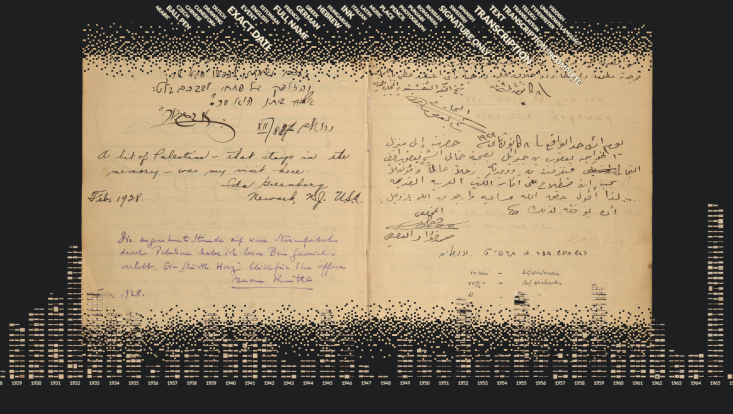

‘The large-scale digitisation project with the NLI raised some fundamental questions about how we handle digitised material,’ Schirrmeister explains today. ‘We’re talking about a gigantic amount of multilingual and extremely heterogeneous material that is not searchable and that nobody can find their way around without guidance. That’s why I’ve been thinking a lot about how we need to visualise data to make it accessible. What form of presentation allows users with different interests to “stroll” through the material, and how do we increase the chance that they will make intriguing discoveries in the process?’

So the idea for a follow-up project was quickly born: Using a small selection from the huge number of documents digitised with the NLI, the possibilities of digital processing were to be explored and further developed. The Jerusalem guestbook was chosen because of its manageable size and complex internal and external cross-references, which provide excellent illustrative material for how the digital reproduction of a written artefact creates new possibilities for research. ‘When we work with a digital copy instead of the original document, we inevitably lose something,’ says Schirrmeister. ‘The physical context and the haptic impression are missing. We can’t leave our thumb on one page and quickly flip through the whole book looking for another passage – all the things we take for granted when working with physical books. But we have other possibilities that a book doesn’t offer: We can filter by keywords, sort by dates and languages, see at a glance how many entries were made with pencils, and so on. In this phase, we are less concerned with clarifying specific research questions than with seeing what is possible, and hopefully we can be beneficial to other projects as well.’

Even a relatively small guestbook of around 200 pages shows that no single person can comprehend it in all its facets. The multitude of languages in which the entries were written is overwhelming: from Arabic, Hebrew, German, Chinese to cuneiform script, everything is represented. Furthermore, identifying at least some of the unknown people and exploring their relationships to the Ben-Gavriêls and the intellectual milieu they were a part of is a task that can only be tackled collectively. ‘We want the book to be available online so that users can help us to close some of the gaps,’ says Schirrmeister.

In the next step, he and his colleagues want to climb a higher mountain: Instead of a single object, an entire estate – one of the 24 digitised by the NLI and the CSMC – is to be digitally represented. Rather than around 1,200 entries, there will then be around thirty times as many images. The current phase of work is mainly concerned with testing and further developing the necessary functions. ‘We use open-source solutions that already exist, in this case the VIKUS Viewer which was developed at the University of Applied Sciences Potsdam. We play back what we need for our specific project, what works and where there are difficulties. In this way, our application also influences the development of the technology.’

On 23 January, Schirrmeister, together with other researchers from the CSMC and the Hub of Computing and Data Science, presented his work on the Jerusalem guestbook at a public launch event. In short talks, he discussed the visualisation of data, but also the finds that researchers can make thanks to such processing: The stories of Hitler’s art enemy number one, Amos Oz’s famous uncle, and the Nazi who travelled to Palestine – they are all enclosed in the pages of Miryam and Moshe Ya’akov Ben-Gavriêl’s guestbook. New digital techniques help us to tell them.