5 Questions to...Agnieszka Helman-Ważny

27 December 2022

In ‘5 Questions to…’, members of CSMC chat about their background, what motivates them, and their favourite written artefacts. This time, Agnieszka Helman-Ważny explains what studying paper has to do with learning about other cultures – and why her alternative career would have been in forensics.

Agnieszka Helman-Ważny, please tell us a little about yourself.

As a young person, I was fascinated by the process of creating art and its resulting visual communication. At that time, I especially liked drawing people’s faces or making quick sketches of their postures, capturing snapshots of their lives. I often drew the same person many times using different techniques until everything about them was almost ‘coded’ in my mind.

These experiences made me realise how important it is to know the properties of materials and to understand how to use them to transfer concepts or shapes from my mind onto paper. This is why I decided to study conservation at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, a programme that was unique at that time: we did not only study technology and chemistry but also received training in producing manuscripts and bookbinding. I really enjoyed copying the techniques of old masters and learning about paper deterioration processes, and also the bohemian atmosphere at the school I felt I belonged to.

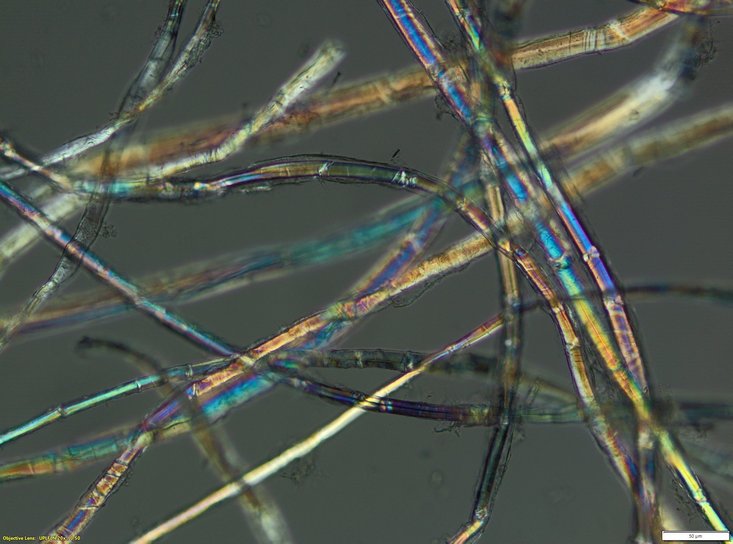

Almost naturally, then, I developed a strong interest in the materiality of books. Learning through experience, I discovered the potential of microscopes (and other tools) and started exploring paper and fibres. I was, and still am, a very curious person who wants to know how things work – maybe this is what pushed me into science. Step by step, I built my own curriculum on the topic of paper.

In 2000 and 2001, I worked under supervision of Professor Nam-Seok Cho at the paper science department of Chungbuk National University in Cheongju, South Korea, and took courses on wood anatomy held by the Swiss botanist Professor Fritz Schweingruber. This led me to dive even deeper into plants, fibres, Asian books, and art. In 2007, I completed my PhD on Tibetan book collections at the Institute of Cultural Heritage at the Nicolaus Copernicus University in Torun, Poland. During my career, I have been working with students and colleagues from various scientific disciplines and at research institutions in different cultural and political environments in Europe, Asia, and the USA. I feel a bit like an academic nomad.

Archival research and conservation surveys led me, in 2003, to re-discover a large and unusual collection of Tibetan books in the Jagiellonian Library in Kraków, which supposedly had been lost during World War II. These kinds of projects always put me ‘on a mission’, occupying me completely until the mystery is resolved. If I had not gone into academia, I probably would have ended up in forensics.

What are you currently working on?

Have a guess… on paper, of course! In general, I continue to work on its history in Asia by examining book collections from different times and places, and aim to improve and develop methodologies to study paper as a writing support. Currently, I am working on various methods in collaboration with the natural sciences to better understand paper on the molecular level, so that the results of material analysis can aid historians and humanities scholars. Sometimes In a sense, I’m in a ‘grey zone’ between the natural sciences and the humanities.

More specifically, I work on various Buddhist and Bon collections in Mustang and Dolpo in Western Nepal, and I am also interviewing craftsmen to document old traditions of papermaking and producing manuscripts in the areas of Luang Prabang in Laos and Chiang Mai in Northern Thailand.

What can we learn about the social and technological characteristics of a society from the way a people traditionally produced paper?

Papermaking in Asia has always been deeply embedded in the daily lives of local communities. People used to produce paper for rituals, art, festivals, medicine, administration, home interiors, and other daily uses, with local tools and materials available in the vicinity. In some remote areas, this tradition of papermaking, which employs methods that are almost as basic as they were at the beginning of papermaking history, has survived to this day. Especially in China, however, this tradition has often been interrupted and re-created for purely touristic purposes. But even in such cases, the demonstrated methods sometimes (but not always!) follow local traditions.

I try to understand the similarities and differences between particular papermaking traditions. To what extent are these differences due to technology and materials, and to what extent are they due to cultural factors? I have been working in the Himalayas since 1997 and thanks to our Cluster, I can now also do research in Southwest China, Northern Thailand, and Laos. Regarding the plants and technologies used, their religious beliefs, and organisation of labour, there are indeed many similarities across these cultures. So, yes, by studying paper we can really learn much about societies, cultural habits, technology, knowledge transfer, and sometimes even religion, both within and in between communities and ethnic groups.

You have been part of CSMC from the very beginning, that is, for more than ten years. With this experience, where do you see the main advantages of and the main challenges for a large cross-disciplinary research institution?

Indeed, I have been around since the early stages. I met Professor Michael Friedrich and Professor Jörg Quenzer around 2007, and I was the first scholar invited as a fellow researcher by Manuskriptkulturen in Asien und Afrika (FOR 963) in 2008. It’s incredible how time flies, but it has been and still is a great pleasure to see how the ideas born back then have been developing into today’s Cluster of Excellence. Its cross-disciplinarity is at the same time its biggest strength and the main challenge. It is absolutely exciting to have such an unusual research scope, but it requires close collaborations between colleagues from the natural sciences and the humanities. This pulls everybody out of their comfort zones, requiring them to learn things from outside their own disciplines. I think we are doing well!

Do you have a favourite written artefact? What is it, and what makes it so special to you?

Yes, of course, a couple of them. Mostly field notebooks or sketchbooks. I guess they are ‘special to me’ because of my early fascination with Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks, their level of detail, and the perfect combination of visual and written information in them. More generally, notebooks are the very first record of ideas with all the context of that particular moment when the idea is born. They show the beginning and the process at the same time, so you can understand how various ideas transform.

Almost every manuscript opens new doors, one by one, revealing its story. Some objects’ biographies are just as amazing as the biographies of persons!