5 Questions to...TianYu Shi

25 March 2022

In our series ‘5 Questions to…’, members of CSMC chat about their background, current work, what motivates them, and about their favourite written artefacts. In this episode, we talk to TianYu Shi, whose work on epitaphs sheds slight on the history of Chinese society beyond the official records.

TianYu Shi, please tell us a little about yourself.

My interest is in the social history of China during the transition from the medieval to the modern period, which roughly covers the time from the 6th to the 12th century. I am mainly concerned with the non-official group in society, that is, people who did not hold public office or were employed by public administration. This group rarely appears in official Chinese historical records but, in my opinion, is nevertheless historically significant.

I received my undergraduate and master’s degrees in Taipei, Taiwan. My master’s thesis at National Taiwan University discussed family burials in the Central Plain Area of China from the 9th to the 10th century. During my research, I became interested in epitaphs. In May 2020, I started my PhD at CSMC.

What’s the topic of your PhD dissertation and why did you choose it?

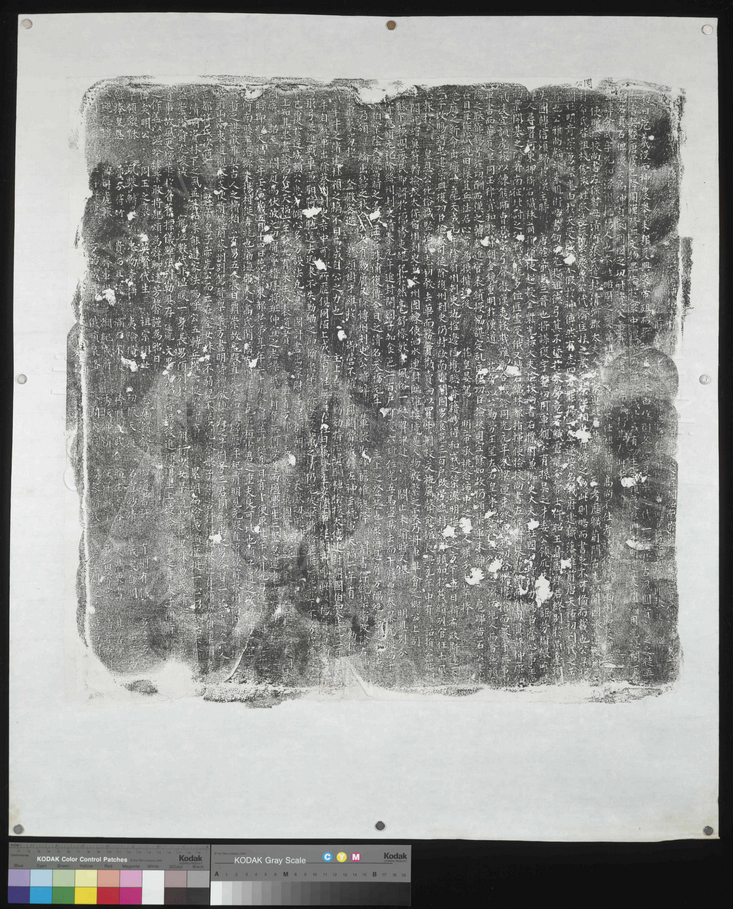

My research explores the significance of epitaphs in public life. Chinese epitaphs can basically be regarded as a person’s biography carved on a thick stone slab. Therefore, historians have used it to study people not recorded in Official Histories.

My project focuses on the materiality of epitaphs. It costs a lot to acquire an epitaph for a grave. Why would the family of the deceased be willing to spend money for it? What do they expect to gain from this act and from the epitaph itself? How did they obtain it? Who are the people who are expected to read the epitaph? All these questions relate to the impact of the epitaph on public life.

My resources come from the epitaphs themselves and from other historical materials documenting their purchase, processing, display, and circulation. I call these materials the ‘paratext’ of the epitaphs. There are approximately 30,000 epitaphs from the 6th to the 12th century. This number keeps growing with further archaeological excavations and collations. My current work identifies and categorises the paratextual material according to geography and time and seeks to offer a universal interpretation.

The traditional culture of epitaphs has gradually disappeared.

What is it like for you when you’re at a cemetery? Do you pay more attention to (modern) epitaphs? And do you discover differences between Chinese and German epitaphs, for example?

I have not visited many cemeteries in Hamburg yet, but I will when I have the opportunity. As for the epitaphs in China, they are becoming less and less common. After the People’s Republic of China was founded, cremation was implemented on a large scale and various burial methods were promoted to save space in recent years. Nowadays, most of the graves only have a small stone tablet with the name and a photo of the deceased. Although the traditional culture of epitaphs has gradually disappeared, it is interesting to discuss the process of this cultural disappearance and especially people’s response to the change.

There is a big difference between Chinese and German epitaphs (or, more generally, epitaphs in the Christian tradition). Simply put, Chinese epitaphs are strongly related to biographies in Official Histories (zhengshi, 正史) which each dynasty compiles for the previous one, including biographies of everyone from the emperor to famous officials and literati. This tradition was kept for almost two thousand years. Epitaphs adopted the style of biographical writing, and in some cases, the Official Histories would use the text of people’s epitaphs.

I am not an expert for epitaphs in the Christian tradition. Most of the ones I have seen only consist of concise mottoes and aphorisms in seal script. Of course, as I delve deeper into the study of Chinese epitaphs and learn more about the purpose for which they were written (including the religious background, social relations, et cetera), interesting points of comparison between Chinese and Western epitaph cultures might emerge.

What is it like for you to work at an institution like CSMC and with so many researchers from different disciplines?

This is both a challenge and an opportunity, in two ways: First, sinology is not a mainstream discipline in Hamburg, so I often have to answer questions about the context of my research and what it contributes to the academic community. Addressing these questions is very helpful as it allows me to constantly improve my general research approach and my arguments.

Second, working at CSMC allows me to learn about different research paradigms. In China, funerary matters are considered private family matters, and most details are not made public or even recorded. I want to draw on sociological and anthropological approaches to uncover the clues hidden in these texts. At CSMC, I interact with researchers in these fields, learn about their work first-hand, and use this to enrich my own work.

Do you have a favourite written artefact? If so, what is it and why is it so special to you?

My favourite written artefact is the epitaph for Chao Juncheng 晁君成 (1029-1075) by the famous scholar Huang Tingjian 黃庭堅 (1045-1105). I like this epitaph not so much for its content but its story. Chao Juncheng was not a famous official. His son, Chao Buzhi 晁補之 (1053-1110), had a higher social status than he did. In order to pass on his father’s deeds to future generations, Chao Buzhi used all his social connections to find a famous person to write Chao Juncheng’s epitaph. Unfortunately, Chao’s financial resources were limited. Finding a celebrity to write the epitaph took so much time that Chao Juncheng’s coffin remained unburied for years.

What is interesting about this story is the difficult choice facing Chao Buzhi. According to traditional Chinese ritual norms, the burial of a family member needs to be completed as quickly as possible within a few days after the death. But on the other hand, seeking a famous person to write the epitaph in order to gain fame for the deceased was also seen as an important part of traditional ritual. Chao was in a dilemma: either way, he would have carried a degree of censure and would not have been able to conform fully to the norms of traditional Chinese rituals.

TianYu Shi

is a PhD candidate at CSMC. He works as a research associate on the project 'The presence of inscriptions in public life from 617 to 1276 CE in China', which belongs to 'Inscribing Spaces' (Research Field B) at the Cluster of Excellence 'Understanding Written Artefacts'.