Architectural plans on clay

24 March 2024

Architects have always drawn up plans, graphic representations of the buildings they were commissioned to construct. Mesopotamian architects left plans drawn on clay tablets. These documents constitute a unique corpus that bears witness to the working methods of this profession, which was at the origin of buildings that have now disappeared.

The building material par excellence was unbaked clay bricks, which were used to build both private houses and the great ziggurats, monumental multi-storey towers with a religious function. Because bricks did not stand the test of time, the Mesopotamian remains are not as impressive as the Egyptian pyramids or the Achaemenid palaces built of stone.

Administrative tablets from the end of the third millennium provide abundant details on the construction of the ziggurats, including estimates of the number of bricks to be made and the number of workers to be employed. For example, a thousand workers were employed over a period of five months to make the 7.6 million bricks needed to build the first terrace of the monumental ziggurat at Ur. And it probably took some 36 million bricks to build the Babylonian ziggurat, the origin of the biblical myth of the Tower of Babel.

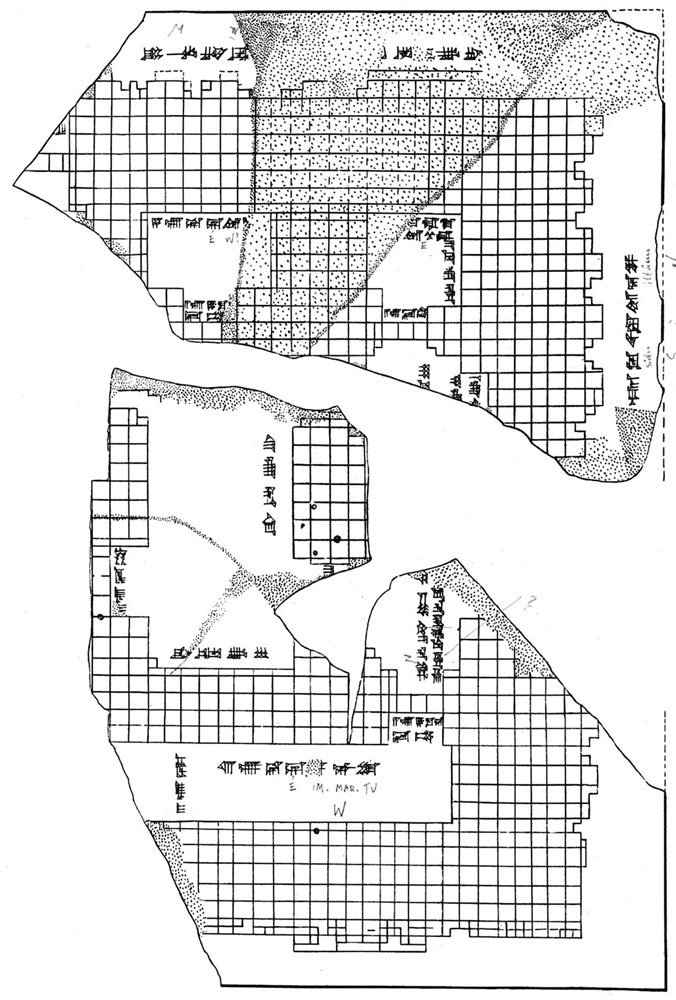

Since such constructions are presented as the great work of kings, the names of the architects who drew up the plans and directed the work remain unknown. All that remains are their anonymous plans, which sometimes reveal a mastery of cartographic techniques. From simple sketches drawn freehand, the most elaborate plans, drawn with a ruler, show the walls with two parallel lines stopping at the openings between two rooms or towards the outside. A plan discovered in the town of Sippar Yahrurum curiously does not show any openings to the outside of the building.

The cuneiform annotations on some of these plans give the lengths of the walls, the internal dimensions of the rooms, and even the thickness of the walls and the width of the openings. The dimensions, which are on a human scale, use the cubit and the finger. Some building plans indicate their orientation in relation to the points of the compass.

A plan of Girsu dating from the end of the 3rd millennium gives the names of the rooms in the building and their dimensions. Although the measurements are correct, the plan does not respect the proportions, which is often the case. On the other hand, a temple plan discovered at Sippar and dating from the 6th century BCE is so detailed that it shows the arrangement of each brick in the walls and the decoration on the outside. The fact that the bricks are of such precise dimensions means that their sizes can even be compared with those found on Mesopotamian sites.

To achieve such a high degree of precision, architects, like surveyors, must have been trained in mathematics, which enabled them to draw up their plans. The profession of architect was certainly a prestigious one. The inscriptions of Prince Gudea of Lagash (circa 2120 BCE) show that he took a close interest in the architectural details and construction techniques of the monumental buildings he ordered to be built. He undoubtedly had some knowledge of the subject, as two of his statues depict him, one with the plan of the Ningirsu temple drawn on a tablet on his lap and the other with an architect's ruler.

Mesopotamian architects would have deserved to leave their names to posterity, just like the Egyptian Imhotep, sculptor, architect and vizier to the king, who is said to have designed and supervised the construction of Djoser's funerary complex at Saqqara, with its stepped pyramid.