Excavations and restorations: Iraq (re)discovers its archaeological heritage

29 January 2022

Archaeologists are back in Iraq. First in Iraqi Kurdistan since the mid-2000s, they have also resumed their activities in the south of the country where they are making important discoveries. Archaeological excavations and restoration work are increasing significantly in a country that has been ravaged by decades of war.

In the south of the country, the British, in cooperation with a local team, have uncovered the temple of the god Ningirsu built by the Sumerian king Gudea (22nd century BCE) at the site of Tello, the ancient Girsu, as well as a large bakery attached to it. They are also working on the restoration of the ancient bridge, one of the oldest in the world, discovered in 1920.

In the city of Uruk, a German-Iraqi team is working to restore ancient buildings, such as the white temple of the god Anu, by shaping moulded clay bricks in the traditional way, which they dry in the sun.

The French, for their part, have been back in Larsa since 2019, about twenty kilometres east of Uruk, after being forced to leave in 1989 due to the Gulf War. In cooperation with the Iraqis, they made multiple discoveries during the mission which ended in November 2021. Some bricks bear a dedication in cuneiform characters to the sun god Shamash by King Sîn-iddinam (1849-1843). Other similar bricks had been discovered in the Ebabbar, the temple of the god in Larsa. The king is said to have died, crushed by a block, while entering this temple. The team also uncovered the residence of the grand vizier of King Gungunum (1932-1906) and his successor Abi-sare (1905-1895). No fewer than sixty cuneiform tablets, transferred to the Iraq Museum in Baghdad, bear witness to the activities of this dignitary.

Archaeologists are also continuing their work in Iraqi Kurdistan. A team from Udine and researchers from the Department of Antiquities in Dahuk have uncovered fourteen stone basins carved in white rock that served as huge wine presses under King Sennacherib (704-681). And just north of Mosul, on the bank of the Faidi Canal, twelve limestone reliefs depicting the king with deities and other mythological figures are now to be restored and protected from modern construction. This Assyrian king was known for his hydraulic works that supplied water to the inhabitants of the city of Nineveh, and for his wonderful gardens.

The time for restoration has also come in the museums after the destruction caused by Daesh. The Mosul Museum, targeted by the jihadists between 2014 and 2017, was particularly hard hit. Smaller objects were sold on the antiquities market while larger works were smashed to smithereensin staged acts of destruction for propaganda purposes.

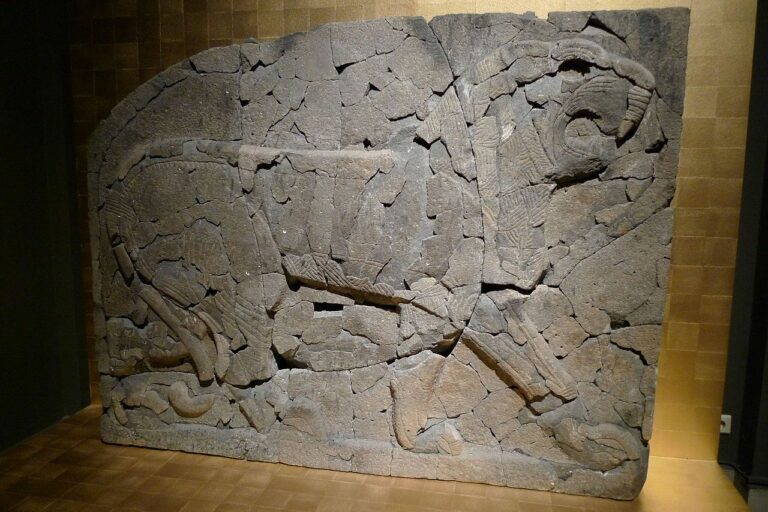

Today, museum staff are trying to piece together a 3D puzzle from the rubble to reconstruct several monumental statues. They are assisted by curators from the Louvre Museum under the direction of Ariane Thomas, director of the Department of Oriental Antiquities, as well as teams from the Smithsonian Institution in Washington and the World Monuments Fund in New York. They receive financial support from the International Alliance for the Protection of Cultural Heritage in Conflict Areas. Their efforts focus on the remains of ancient Kalhu. These include a winged lion and two winged bulls with human heads, figures that the ancients called lamassu, or protective genies. They are also trying to reconstruct the base of the throne of King Assurnazirpal II (883-859) for which they have so far identified 850 fragments.

The reassembly of the statues in the Mosul Museum is reminiscent of the extraordinary puzzle that the Germans put together on the remains of Tell Halaf. These massive sculptures were discovered and collected in a private museum by the diplomat, spy, and archaeologist Max von Oppenheim in 1930. In 1943, his museum was bombed by Allied troops. Attempts to extinguish the fire subjected the basalt statues to thermal shock, and they burst. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, the 27,000 basalt fragments stored in a warehouse in the Pergamon Museum were patiently sorted and the monumental statues reconstructed. They have been on public display since 2011.

The archaeological excavation of mud constructions in the Near East and the work of a museum curator require special knowledge, which could not be transmitted during the war years. The training of Iraqi colleagues through joint missions is one of the main reasons for these scientific operations in Iraq. New generations of Iraqi archaeologists will be able to uncover and enhance the cultural heritage of this cradle of humanity.