The Hanging Gardens of Babylon were at … Nineveh!

30 January 2018

The Hanging Gardens of Babylon, one of the Seven Wonders of the World, vaunted by the Greek-speaking authors, for a long time intrigued both scholars of cuneiform texts and the archaeologists who had the opportunity to excavate the ancient site, because neither of them found any evidence that the gardens actually existed.

Some work carried out by the British Assyriologist Stephanie Dalley suggests that we were misled by the Greeks, and that the famous gardens were in fact located at Nineveh.

In the third volume of his Babyloniaca, a tale recounted in Greek that brought to the attention of Antiochus I what was known of the Babylonian civilisation at the beginning of the third century BCE, Berosus, a priest of the Babylonian god Bel Marduk, attributed the construction of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon to Nabuchodonosor II. The king commanded the creation of some sumptuous terraced gardens for his wife. The subject was taken up again and added to by Diodorus of Sicily in the first century BCE, and subsequently by Flavius Josephus who, quoting Berosus, wrote (Contre Apion, XIX, 140-141):

After having fortified the city in a remarkable way and adorning its gates in a manner that befits their sanctity, (Nabuchodonosor) built close to his father’s palace a second palace adjoining the first […] In this royal residence he built terraces of stone, verily giving them the look of hills; he then planted on them all manner of trees, and set up what one calls hanging gardens, because his wife, who grew up in the Median lands, had a taste for mountainous landscapes.

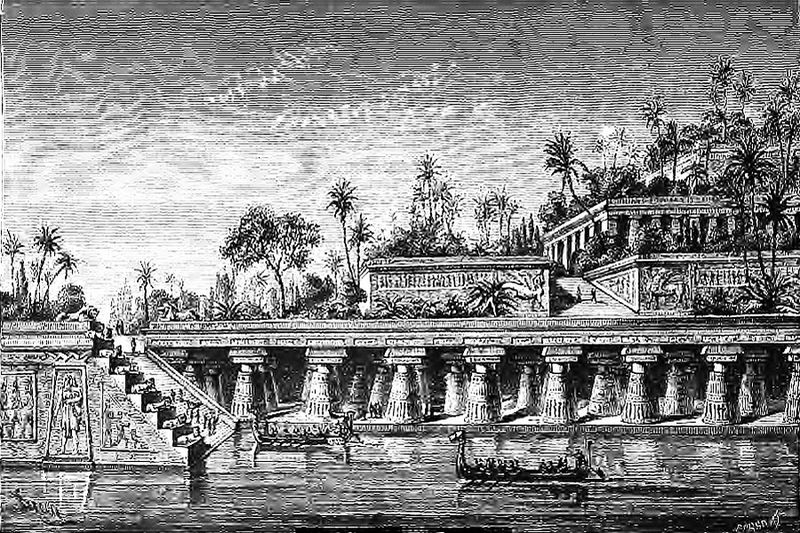

The description of these ‘hanging gardens’ has fascinated generations of artists who have given free rein to their imagination when depicting them in their works.

However, no trace remains of these celebrated gardens. R. Koldewey, who explored the site of ancient Babylon between 1899 and 1917, hypothesised that they were situated on the roof of a vaulted building that constituted part of the southern palace. But this hypothesis has not been supported by all the scholars who have followed in his footsteps. The Babylonian royal inscriptions do not offer any descriptions which could relate to these mysterious gardens, interpreted as monumental planted terraces.

In 2013, Stephanie Dalley published an enthralling investigation in which she suggested that the gardens were in fact located at Nineveh, where they were set up by King Sennacherib at the beginning of the seventh century BCE.[1] This conclusion is above all based on a series of observations. The gardens are not mentioned in the writings of Herodotus, yet he described at length the lives of the people of Babylon. The gardens only appear in writings of the Hellenistic and Roman periods. Now, the Greeks often confused the two ancient metropolises of Babylon and Nineveh, the respective capitals of the Babylonian and Assyrian empires. In his inscriptions, Sennacherib (704–681 BCE), the king of the Neo-Assyrian empire, alludes to his new residence, the ‘Palace Without Rival’, as well as the gardens that surrounded it:

I have planted around its sides a botanic garden, a replica of Mount Amanus, which contains all sorts of aromatic plants (and) fruit trees […] To promote the luxuriance of these cultivated areas, I have had dug with pickaxes a straight canal that cuts through the mountain and the valley, beginning at the city limits and running up to the plain of Nineveh. I have released an inexhaustible flow of water for a distance of one kilometre and a half from the River Husur (and) I have made it so (water) gushes through the garden carried by feeder channels.

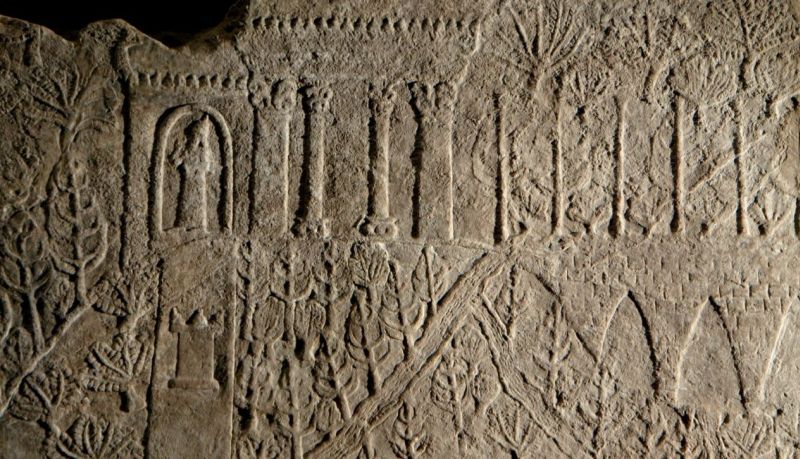

The bas-reliefs at Sennacherib’s palace offer a depiction of these gardens planted with trees and equipped with an aqueduct and a system of channels that made it possible to supply elevated irrigation. In his inscriptions, the king fittingly mentioned the invention of a lifting device that made it possible to raise water using a system that was a precursor of the famous ‘Archimedes’ screw’:

I had ropes made, and cables and chains of bronze. Instead of pivots (i.e. shadoofs), I had tree trunks put in place and some large copper helicoids (alamittu) positioned above the wells.

If from now on we must suppose that the famous ‘Hanging Gardens’ were actually located in Nineveh, it is only thanks to Babylon’s fabled walls that it can retain a place on the list of Wonders of the World!

[1] Dalley, Stephanie (2013), The Mystery of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon: An Elusive World Wonder Traced, Oxford: OUP Oxford.