Excavating in EgyptA Day in the Field

4 March 2022

Extreme heat, strong winds – and at every turn the danger of accidentally damaging unique cultural objects. Excavations in Egypt are a physical and mental challenge for everyone involved. In her report, Leah Mascia describes the difficulties and the joy, and shares the story of a very special find.

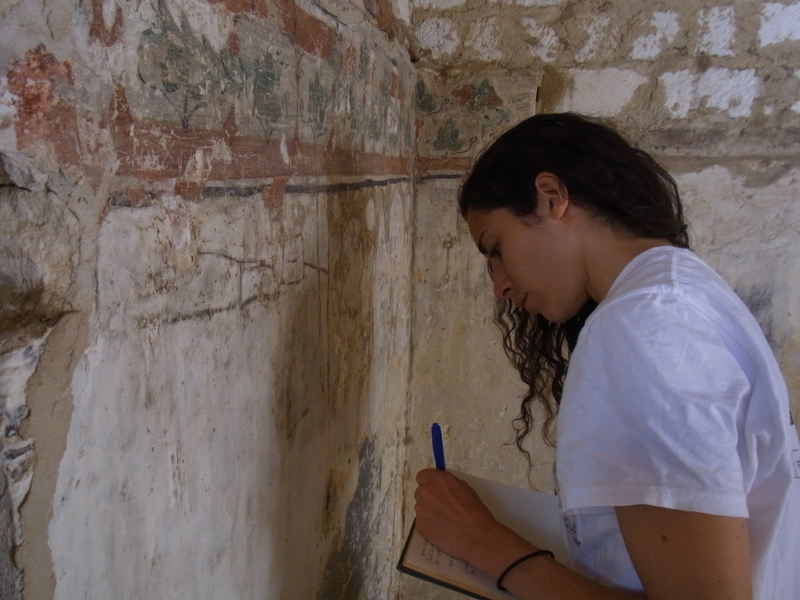

Working in the field in Egypt is an incredible experience – but it is far from being a simple endeavour. For me, the campaign does not begin with the excavations themselves but rather with preparing a detailed schedule of activities that I’m planning to carry out while on-site. For instance, at the beginning and the end of each archaeological campaign, part of my time is devoted to studying the unedited Coptic written artefacts discovered in previous years. Many of them are now preserved in the archives of the Egyptian Antiquity Service. Others must be examined on-site, like the graffiti that we are currently documenting in the basilica of Sector 24.

The team of the mission of the University of Barcelona lives together for more than a month on the archaeological site of Oxyrhynchus (modern el-Bahnasa), working six or even seven days a week if something important has been found. Because of the heat (after 8:00 am, the temperature normally exceeds 30ºC), the day starts early in the morning. We wake up at 5:00 am and at 6:30 we begin to excavate on the site, which is within a short walking distance from the mission house. We normally work until 1 pm. The rest of the day we spend studying what we discovered during the investigations. On a normal workday, me and the team are digging in the so-called Upper Necropolis of Oxyrhynchus. Since I’m in charge of the preliminary examination of many inscribed materials found during the excavations, my work also depends on what we have found during the day or the previous days.

In 2021, we discovered the mummy of a child wearing a package with several folded sheets of papyrus on the chest, carefully sealed with a clay device. When the tomb was identified, we immediately stopped the excavations and delimited and cleaned the area with trowels and dustpans. Then we began to examine the mummy with our team of anthropologists, gently removing the sand with various tools, thus determining the exact location of the manuscript. While at this stage it is essential to take as many photographs of the evidence as possible, an in-depth autoptic analysis is equally important. Considering the fragility of the papyrus package, it was vital to avoid any direct contact with the artefact. Therefore, I proceeded to carefully observe the manuscript, wrote down a brief description of its main features in my notebook, recorded its position in relation to the mummy, and collected all the information the archaeological context provided.

The restorers then started with the first preventive interventions and safely covered the object with protective materials before removing it. To avert any damages that the transportation might have caused, we did not go to the laboratory by car but preferred to walk although it’s a distance of about one kilometre. I cannot describe the fear you feel when you’re carrying a 2000-year-old sealed papyrus with your own hands.

The excitement and happiness about the discovery are quickly followed by the fear of losing precious information.

While an ostracon or a stela require a procedure that we are used to and carry out frequently, the discovery of papyri and inscribed cartonnages can give us a really hard time, as this episode reveals. The excitement and happiness about the discovery are quickly followed by the fear of losing precious information. It only takes one wrong movement or a breath of wind. For this reason, we work with extreme caution, but also as quickly as possible. For numerous reasons, examining and preserving these written artefacts is far from easy: the extreme fragility of the material supports, the sun, and changes of humidity can all rapidly deteriorate the texts. Then there’s the sand that might fall into the tomb (and it always does!) caused by the vibrations of even a single step. Last but not least, there is the strong wind that is characteristic for this area of Egypt. One can only imagine the intense pressure and responsibility that we feel when working on these artefacts, especially considering the uniqueness and importance of our findings.

After we had safely reached the laboratory, the consolidation and cleaning of the folded papyrus started, which is another difficult procedure. The writing is often not easily legible since rising levels of underground water frequently damage the materials inside the tombs. For this reason, it is essential to carry out this process with great patience; it might take several days (and evenings). During the gradual restoration procedure, I carefully analysed the manuscript, like I always do, not just concentrating on the text but also on all other elements that might provide further insights, from the production to the actual function. Given its precarious condition, we decided to study only the outer papyrus sheets of the package, waiting for further non-invasive analysis methods to examine its content.

Despite the difficulties that we encounter during our intense fieldwork, the experience that we acquire on-site is essential to our research. The feeling of having witnessed such unique discoveries increase the passion for our work and for this extraordinary site.

Leah Mascia

is a PhD student at CSMC. Her dissertation project is called 'The Transition from Traditional Cults to the Affirmation of Christian Beliefs in the City of Oxyrhynchus'. More information about the excavation, including some images, is available here.