Material Characterization of Thai Manuscripts

Olivier Bonnerot, Sean Ngiam, Sowmeya Sathiyamani

Thai MS 6 is part of a group of written artefacts from South East Asia that were loaned to the CSMC for scientific investigation. Although three of the four WAs were already dated by colophon, the modern materials allowed the post quem material dating of some of the WAs. The manuscripts were examined with a multi-analytical approach, using several techniques including Infrared Reflectography (Apollo mobile imaging system), Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (Agilent Exoscan), Raman spectroscopy (Renishaw inVia Raman spectrometer), optical microscopy (Olympus BX51) and X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (Bruker ARTAX and M6 Jetstream). The results revealed the use of a combination of traditional and modern writing materials for their production (see What is my WA made of?) (Sathiyamani et al. 2024).

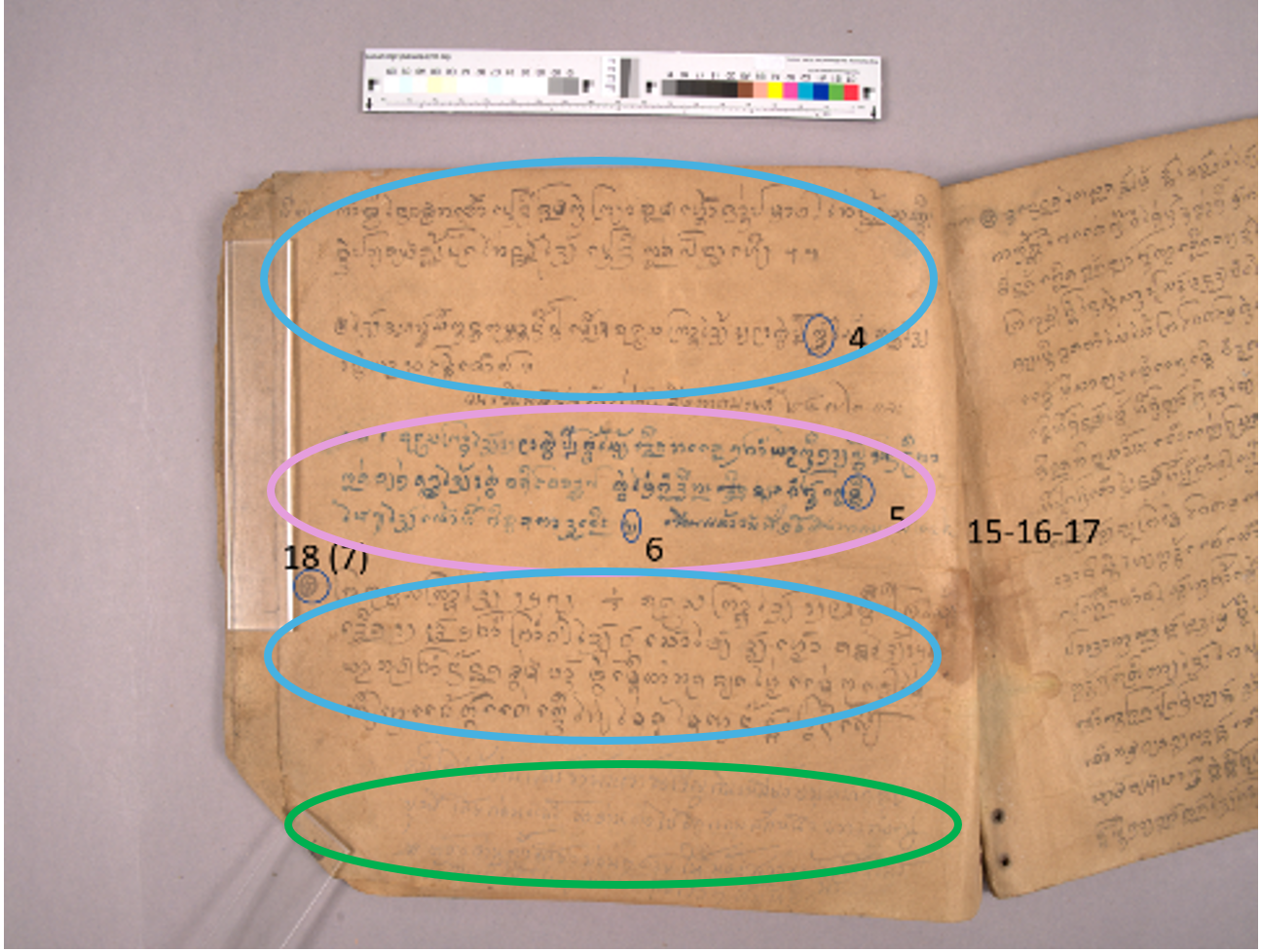

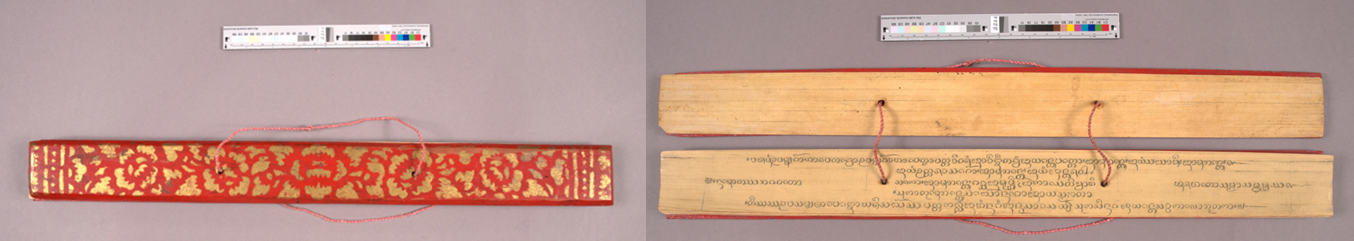

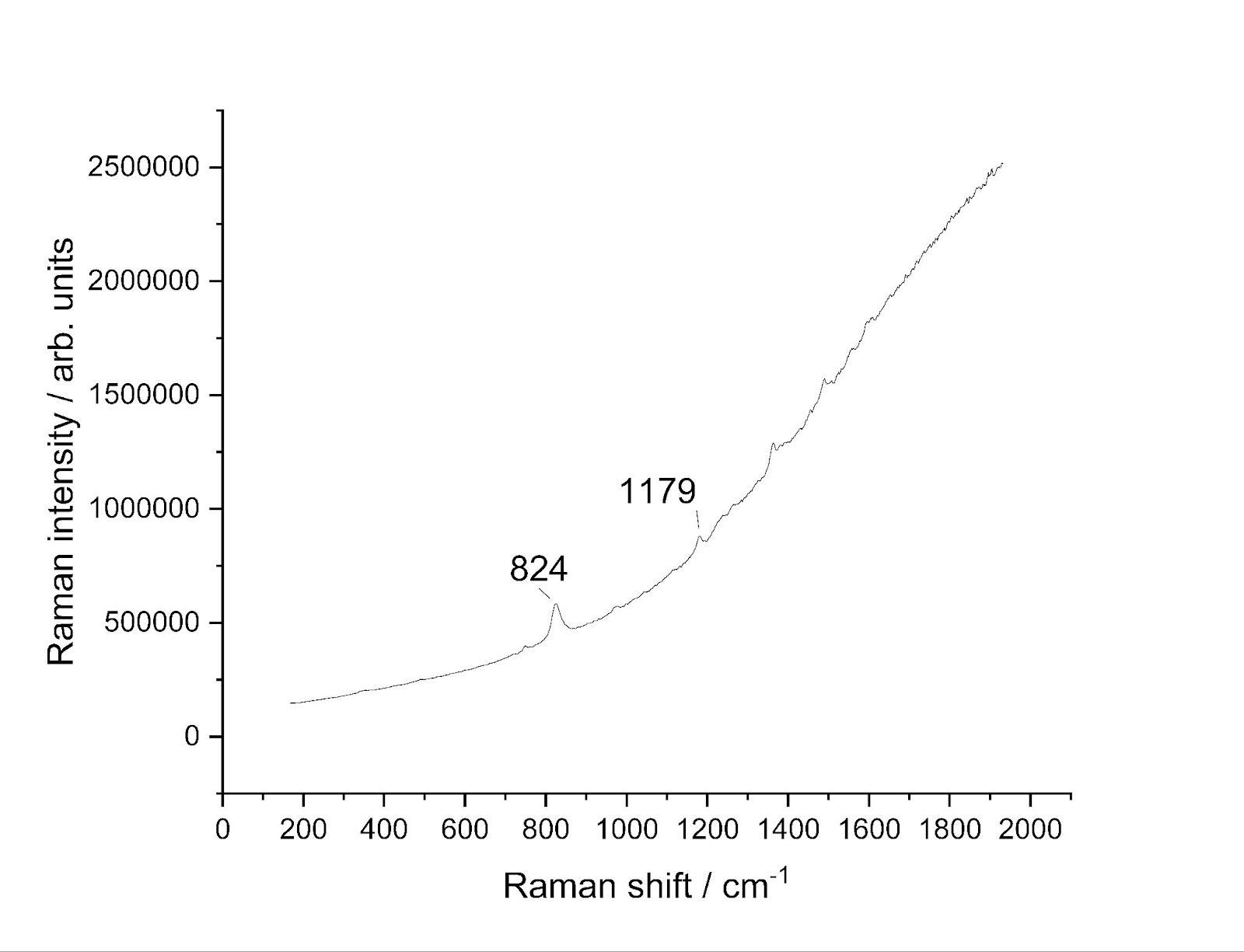

For the two palm-leaf manuscripts, MS 6 and MS 7, the text was first inscribed on the surface with a stylus, followed by the application of the traditional black soot paste to make the text legible. They are bound by a red thread that passes through a pair of aligned holes in the centre of the bundle. In addition, MS6 is protected by a pair of red wooden covers (Fig. 1). The pigments used for the cover are much less traditional: the industrial pigment molybdenum orange was identified with Raman spectroscopy with characteristic peaks at 824 and 1179 cm-1 (Fig. 2, Chua et al. 2016). This pigment, patented in Germany in 1930, was not very common in the palette of 20th century artists, but was identified in the 1970-1971 works of the Japanese artist Haku Maki (Chua et al. 2016). Interestingly, the colophon (on a leaf which was apparently not part of the original bundle) indicates that MS 6 was donated in 1970. The presence of molybdenum orange on the cover may suggest it was an addition from the time of the donation (see How to date my WA?).

Investigation of the paper artefacts (MS 3 and MS 4) also revealed a blend of traditional and modern materials. MS 3, dated by colophon to 1929 CE and 1934 CE, was partially written in methyl violet ink (Fig. 5) (first synthesised in the late 19th century) on industrially made paper comprising wood fibres (Fig. 4), a feat not technologically possible until 1840 CE and which was, even then, rare until the sulfite and kraft processes were invented in the late 1850s CE and 1879 CE, respectively. MS 4, dated by colophon to 1851 CE and 1855 CE, contained kaolin clay in one of the two types of paper identified in the WA (Fig. 3). The paper type containing kaolin was thicker by some 94% than the paper type without kaolin. In addition, the fibres comprising both types of paper writing support in MS 4 were identified under optical microscopy as Streblus asper (Sathiyamani et al. 2024), native only to parts of Southeast and South Asia. While the species has been used in Thai papermaking for over 700 years, kaolin clay was only initially used as a filler c.1807 CE in the West (Hunter 1978).