Text of Manichaean Papyri Recovered with MSI

Kyle Ann Huskin

In the 1920s six large papyrus codices were unearthed at Medinet Madi in Egypt’s Fayyum desert. They were written c.400 CE in Coptic by several scribes and contain translations of Syriac texts by the prophet Mani (c.216–277 CE) and other foundational writings of the Manichaean religion. After being sold on the antiquities market in 1931, the codices were dismantled page by page (as far as conservation allowed), and each fragment now lives between glass or Perspex plates. The pages were divided between the Berlin’s Ägyptisches Museum und Papyrussammlung and Dublin’s Chester Beatty Library, though some plates from the former institution now reside in Warsaw after being looted during the Second World War.

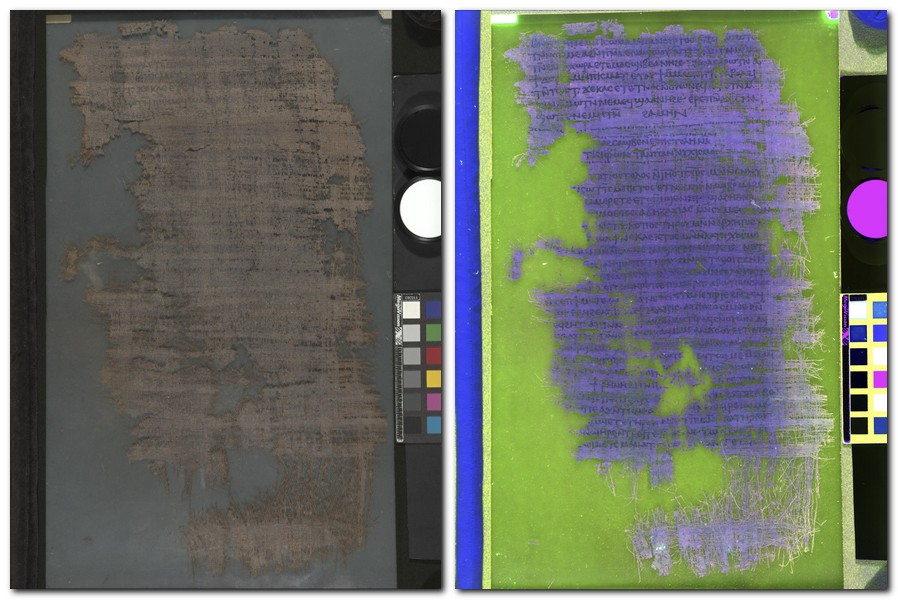

One codex (Berlin, ÄMP, P.15998) contains what appears to be a ‘canonical’ compilation of letters mostly written by Mani himself, with varying degrees of scribal intervention, that served an important role in practising and transmitting the religion (Gardner 2022, 2–5). The fragments are heavily damaged and the ink is so faded that some pages appear almost blank. Therefore, after over two decades of trying to edit the texts of P.15998, the scholars turned to multispectral imaging (MSI) to increase readability. The first MSI campaign of was undertaken in 2019, with a small additional campaign in 2021 for the Warsaw fragments. The ‘astonishing’ MSI results resulted in ‘a substantial increase in the total amount of readable text, which might approximate to an additional fifty per cent beyond the first draft edition of 1995’ (Gardner 2022, 10).

The MSI data was captured with the MegaVision system using the 50-megapixel E7 camera sensor. However, text recovery would not have been nearly as successful without concerted image processing (see How Can I Study My WA If I Only Have Digital Images?) efforts.

In addition to MSI, ink analysis was done with X-ray fluorescence (XRF) using the Elio device on another Medinet Madi codex (Dublin, Chester Beatty Library, PMA 5), and the results show that the text was written in a vitriolic iron-gall ink (Bonnerot, Shevchuk and Rabin 2020). Although a single production campaign cannot be assumed for the various Medinet Madi codices, they were written in the same Coptic dialect within a few decades of one another and share codicological similarities in terms of size and binding (Gardner 2022, 3); it is therefore probable that P.15998 was also written in a vitriolic iron-gall ink.