Codex

Caroline Macé, Thies Staack

Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Hamburg

The term codex (used in English since 1661, according to OED) is a borrowing from Latin caudex, originally meaning wood block (Lewis and Short 1879, s.v. ‘caudex’), thus hinting at a possible origin of the codex form as a gathering of wood tablets, much like Paris, Louvre, MNE 914.7 (see Tablet and Book). In later Greek the word κώδιξ (kōdix) / κώδηξ (kōdēx), borrowed from Latin, primarily meant a “code” of laws. The term “codicology” usually indicates the study of the material aspects of books, and not only of codices.

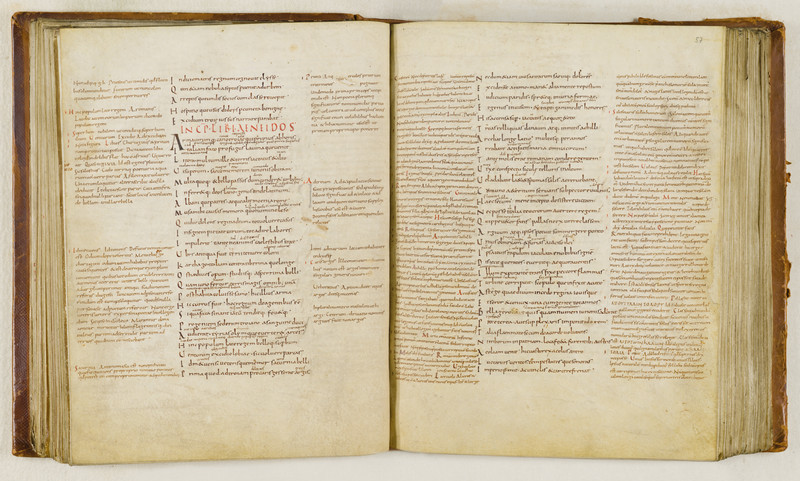

Based on the type of ‘western’ manuscripts that is usually labelled as codex, Muzerelle defines this form as a “book made up of sheets folded in half and assembled into one or more quires stitched together with a thread along the fold” (Muzerelle 2002–2003, s.v. codex; Macé’s translation). In the context of the present definition of codex, therefore, the characterising feature is the presence of quires (vs Book) – the literature is yet to reach an agreement in this respect, though (cf. Andrist and Maniaci 2021; updating Andrist, Canart and Maniaci 2013, 45–48). Such ‘western’ codex emerged towards the beginning of the so-called “common era” and rapidly became the dominant book form around the Mediterranean and in the areas influenced by the Greco-Latin culture (Maniaci 2015), i.e. the Roman and Byzantine empires, the Christian oriental cultures, the Slavs, the Manicheans and the Arab-Islamic world, with percolations into the Hindu, Sikh and Jain traditions in India. By contrast the Jews continued to use the volumen up to the end of the ninth century CE (Beit-Arié 2021, 44; see Scroll/Roll). On the origin of the codex in the West, see Turner 1977, Roberts and Skeat 1987, Blanchard 1989.

In China the codex made its appearance at the latest in the ninth century, almost certainly due to contacts with ‘western’ cultures via Central Asia (Galambos 2020, 12): part of the Dunhuang codices were in fact sewn/stitched and structurally identical to ‘western’ codices, The oldest dated Chinese example is from 899 CE, but some of the undated codices might even be from the eighth century CE (Drège 1979, 17–18).

As only a limited number of materials offering a writing surface can be folded and stitched, a codex is de facto made of papyrus, parchment, paper or bark, and these materials are normally inscribed with black and coloured inks. Although the codex form continued to be used in the printed world up to today, the word “codex” is normally used for handwritten books only.

Because it is possible to dismantle and rebind it, the codex is possibly a modular and evolving object, made of “codicological units” (folio, bifolio, quire) that may have different fate and circulation. See Andrist and Maniaci’s Syntax of the Codex (Andrist and Maniaci 2021; updating Andrist, Canart and Maniaci 2013).