Pothi

Giovanni Ciotti

CSMC

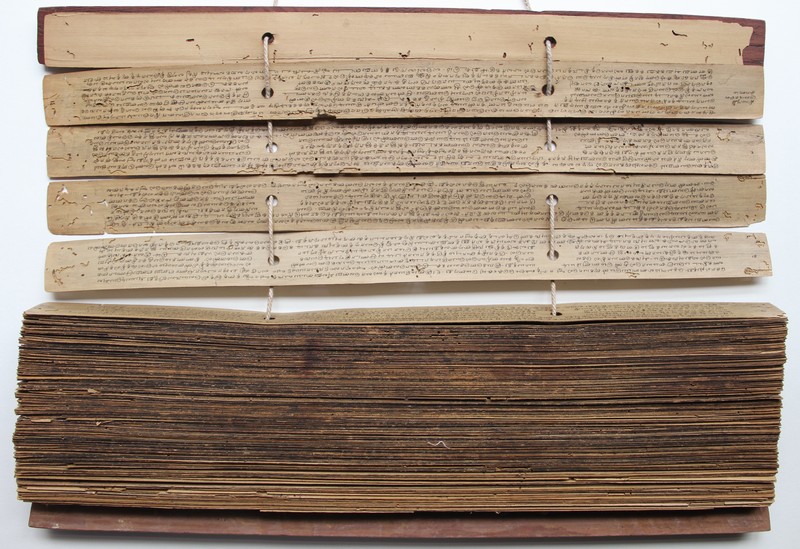

The term ‘pothi’ (pothī) can be used as an umbrella term for any manuscript that is made of a stack of folios in landscape format that are flipped upward rather than sideward (such that the writing on the verso would be upside down if the folios were to be flipped sideward). Historically, this form was prominently used in South and Southeast Asia as well as Tibet, but also to a lesser extent in other areas of Central Asia (where very rarely the folio orientation can happen to be in portrait format and the flipping sideward) (Ciotti 2021, Galambos 2020, 25–27).

The folios of pothis can be made of a great variety of materials. The most commonly used were the leaves of different palm-trees (Talipot and Palmyra), the bark of various trees (Birch and Agarwood tree) and several kinds of handmade paper. More rarely, folios were made of silk, leather, poplar wood, metal sheets (silver, brass and tin) and ivory (Ciotti 2021).

The most sophisticated folio processing happens in the case of the so-called kammavaca manuscripts (kammavācā, “words for the ritual”), i.e. Burmese pothis produced at the occasion of the ordination of a new Buddhist monk. The folios of some of these manuscripts are made either with palm-leaves or textiles that are first stiffened by applying layers of clay and lacquer and then gilded and finally written upon with lacquer (Isaacs 2014, 34; Ward 2015, 72).

The folios of a pothi can be strung together by means of a thread (usually made of cotton) that runs through holes pierced on their surface or left unstrung, simply stacked upon one another, as is typical in the case of paper pothis from North India and Tibet (see Folio). Furthermore, both strung and unstrung stacks can be placed between wooden boards (more rarely metal or ivory), wrapped inside textiles, or in a few cases inserted inside paper sleeves (Ciotti 2023).