Leather and Parchment

Olivier Bonnerot, Kyle Ann Huskin, Grzegorz Nehring

CSMC

Leather is a durable material made from animal skins or hides that have been treated chemically (i.e. ‘tanned’) to preserve the protein structures and prevent decay. The terms ‘hides’ and ‘skins’ refer to the size of the animal from which the raw material was sourced. Specifically, ‘skins’ indicate that smaller animals, such as goats or sheep, were selected, while ‘hides’ refer to those from larger animals, such as cows. Commercial leather production dates back more than 3,500 years, as wages for leather-makers were already regulated at the time of the Hammurabi Code (Covington 2009, 19). Though most commonly used as clothing, footwear, equipment, etc., leather has also been used as a writing surface since at least the 17th century BCE (Reed 1975; Diringer 1982), and possibly as early as the 26th century BCE, as suggested by the inscriptions of the sarcophagus of Weta kept at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo: Weta is said to be the ‘overseer of tanning’, as well as the ‘overseer of the scroll manufacturers’. One of the earliest examples of inscribed leather scrolls is the famous ‘Egyptian Mathematical Leather Roll’ (London, British Museum, EA10250,1), which dates back to the end of the Middle Kingdom (around 17th century BCE) (Glainville 1927). There is a long history of using leather to make Torah scrolls, and a number of texts on leather were found among the Dead Sea Scrolls (Poole and Reed 1962).

Traditionally, leather making involves a series of steps. First, the raw material – an animal skin or hide – is obtained by skinning the animal shortly after slaughter. If the raw hides are intended to be stored before tanning, they are usually salted. To prepare the raw material for tanning, it is soaked in water, which loosens and softens it. Next, the flesh and fat are removed from the skin. Finally, the skin is dehaired, making it ready for the tanning process (Churchill 1983, 1–5). In pre-industrial times, people tanned leather by submerging it in increasingly strong vats of tannin-containing liquid. The resulting products from this process are referred to as ‘vegetable-tanned leathers’, as the tannins used were sourced from different plants. Tannins are classified as hydrolysable(pyrogallol type) and condensed (catechol type). Different plants may be richer in one type of tannins than the others, e.g. gall nuts and sumac usually contain predominantly hydrolysable tannins, while mimosa and quebracho contain condensed tannins (Covington 1997). After being chemically treated, the raw skins and hides become dense, darkened, or coloured, and they can be mechanically processed into various goods. In the 19th century, new methods of mineral tanning were developed in Europe and the United States, with ‘chrome-tanned leather’ quickly becoming the dominant form of leather production due to its faster production time, lighter weight, and increased strength.

Leather properties such as strength and softness depend mostly on the animal species and the chosen areas of skin rather than on the production methods. Here, the factors such tightness of the fibre structure or the amount of fat layer play the crucial role; thus, a leather made from a fine wool sheep will be less resistant to damages but much softer than one made from, e.g. a goat skin (Covington 2009, 65–67).

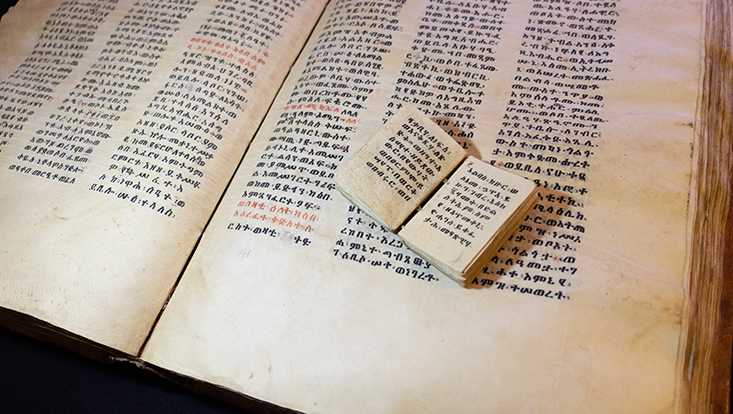

Parchment is another skin-based writing surface. While parchment’s initial production steps (skinning, salting and dehairing) are similar to those of leather, the depilated hides are not tanned; instead, they are put again in lime, washed and stretched to be dried under tension. A series of treatments, such as rubbing with pumice and chalk, are then applied to the wet skin (Hunter 1943, 14). The result is a durable and inelastic sheet, though it remains sensitive to humidity. Similarly to leather, a parchment’s quality depends primarily on the animal’s species and age, as well as the area of skin selected. For example, the thinnest, so-called goldbeater’s parchment is made from cattle intestine (Reed 1975, 85). Likewise, although the terms ‘vellum’ and ‘parchment’ are often used interchangeably, vellum refers specifically to the higher-quality parchment made from calf skin (cite).

Legends attribute parchment’s invention to the city of Pergamon, but many parchments exist from before the rise of the city. In reality, the material probably appeared in the Levant at the beginning of Hellenistic times (many parchment documents from the 3rd century BCE were found among the Dead Sea Scrolls), and possibly much earlier (e.g. the scroll Paris, Musée du Louvre, E7976 from c.1279–1213 BCE is made of a stretched skin material that could already be characterised as parchment). Although parchment is usually not tanned, some Jewish parchments were occasionally superficially tanned (Abdel-Maksoud 2011). For this reason, Jewish parchment may be considered a ‘hybrid between leather and European parchment’ (Maor 2020, 2).

Relevant analytic methods include:

- DNA analysis to identify the source species (Campana et al. 2010)

- PIXE or microprobe analysis to investigate surface treatment (Campana et al. 2010)

- FTIR to investigate surface treatment (Rabin et al. 2010)

- Raman spectroscopy to assess the degree of degradation of collagen in parchments (Schütz et al. 2013)