Erfurt Manuscripts

Olivier Bonnerot, Grzegorz Nehring

In the course of ink studies of Hebrew and Latin manuscripts from mediaeval Germany, we have discovered that the inks produced in Erfurt in the 13th and 14th centuries possessed a characteristic fingerprint that might be used to localise and date these manuscripts (see Where Does My WA Come From?, How to Date My WA?): their iron-gall inks contain an unusually high amount of zinc (Hahn et al. 2007). Further tests have shown that the characteristic ink appeared as the main ink in many manuscripts copied in Erfurt or as paratexts in those manuscripts that were imported there during the aforementioned time. Such inks were found both in Latin and Hebrew manuscripts.

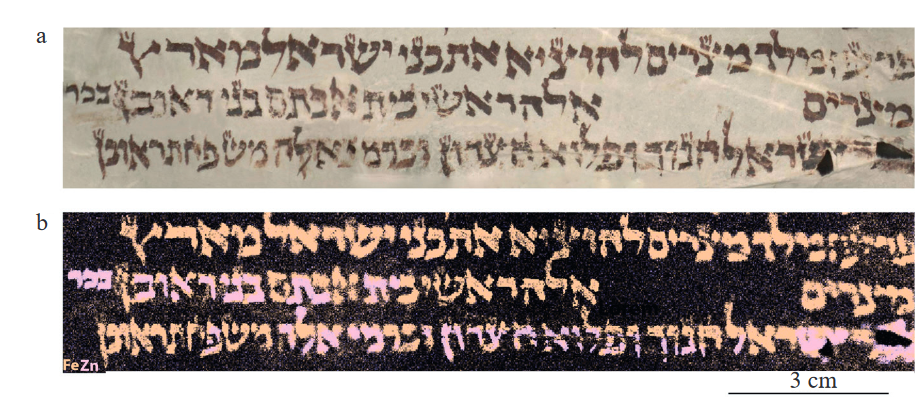

Ms Erfurt 7 (Berlin, Staatsbibliothek Preussicher Kulturbesitz, Ms. Or. fol. 1216), a 13th-century Torah scroll from the famous Erfurt collection kept at the Berlin State Library, is a particularly interesting case study. It has been investigated by combining reflectography with the AD4113T-I2V DinoLite microscope and elemental analysis with the XRF spectrometer Elio from Bruker / XGLab (Gordon et al. 2020). Further insight into the different steps of writing, re-inking and correcting the manuscript were obtained via elemental mapping with the XRF scanner M6 Jetstream from Bruker (Nehring et al. 2021).

Multiple corrections, reinking, and three replacement sheets were identified, which testify to the intense ritual use of the scroll. The inks used for the original and replacement sheets are of different nature (see How Does My WA Change Through Time?), with the latter being rich in zinc, similar to other contemporaneous inks from Erfurt (see Where Does My WA Come From?). Furthermore, the ink analysis confirmed a two-stage process of writing, in which the names of God were sometimes added in the second stage. Scientific material analysis confirms and supplements palaeographical observations, identifying the work of a scribe who filled God’s name into blank spaces in replacement sheets and performed corrections on both the original sheets and the replacement sheets (Fig. 1) (see How Can Different Writing Initiatives Be Distinguished?, How Can My Paleographical Analysis Be Corroborated?). It is suggested that this scribe was a master scribe working alongside an apprentice, a practice with parallels in the Dead Sea Scrolls and mediaeval Hebrew Bible codices.