Manuscripts

Timbuktu emerged in the 12th century as a trading town on the northern bend of the river Niger. Positioned at the crossroads of trans-Saharan trade routes, Timbuktu was actively involved in commercial exchanges between tropical and Mediterranean Africa. The town saw the development and decline of the ancient African empires of Ghana, Mali and Songhay, all of which contributed in various ways to the rich history of Timbuktu. At the height of the ancient Malian kingdom in the 14th century, Timbuktu became known to Europeans through the fame of its rich supply of gold, which lay under the control of the King of Mali. The Catalan Atlas of Charles V of France gives the name of the town as tembuch. The name is written next to an image of king Mansa Musa enthroned and holding a gold nugget. Two famous mosques of Timbuktu – the Jingere-Ber and Sankore – were also built in the 14th century; together with other mosques, they became centres of scholarship and political administration carried out by scholar-families in the town.

As an important intellectual centre, Timbuktu attracted learned men from all corners of the Islamic Maghreb and sub-Saharan Africa. They came from various cultures, including the Berber Sanhaja, the Soninke, the Manding Juula and Jakhanke, the Fulani, the Bambara and even the Visigoths of Spain. One Timbuktu family, the Ka’tis, trace their descent to the Goths of Andalusia through an ancestor who left Granada in 1468 and settled in Timbuktu.

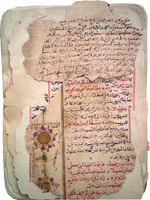

The fame of the town as a thriving place of commerce and the book trade reached a European readership in the 16th century through the famous Moorish diplomat Hassan al-Wazzan (also known as Leo Africanus) who was captured by Spanish corsairs and sent to Rome. In his ”Description of Africa“ he wrote that there were in Timbuktu ‘numerous judges, teachers and priests, all properly remunerated by the king. He greatly honours learning. Many hand-written books imported from Barbary [the Maghreb] are also sold. There is more profit made from this commerce than from all other merchandise’.

Written treasure of West Africa

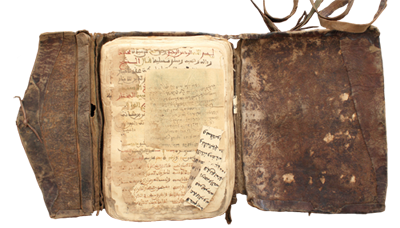

Muslim scholars from the Maghreb and sub-Saharan Africa not only brought manuscripts from various Islamic lands, but also copied and composed numerous texts on a variety of subjects such as Islamic law and mathematics as well as in genres like devotional poetry and historical chronicles. Covering the span of time from the 12th to the early 20th century, the Timbuktu manuscripts epitomise the scholarly and scribal activity in the city and beyond, including the whole region of Mali, its immediate neighbours, and the Mediterranean and central Islamic lands. Until 2012, the manuscripts were held in over 35 private household libraries and in the archives of the State Ahmed Baba Institute. However, the immeasurable value of this written treasure of West Africa is only now being fully understood.

During the last 25 years, many institutions and projects by various Malian and international organisations have been raising awareness of the importance of the Timbuktu manuscripts and slowly making them accessible for research. These initial efforts, and the very existence of the manuscripts themselves, were threatened when political and civil turmoil erupted in the north of Mali in March 2012.

Civil Turmoil and Rescue Operation

The political and civil unrest that broke out in Mali following the military coup of 21 March 2012 led several insurgent groups to overrun the main cities in the north of the country. Timbuktu was taken by the rebels on 1 April, ten days into the conflict. The radical Islamist fighters showed no mercy for the cultural heritage of Timbuktu, destroying UNESCO-protected monuments of venerated Muslim scholars. When the rebels became aware that Timbuktu’s manuscripts were also part of the UNESCO world heritage site, and were considered important by the Western world, the destruction of the manuscripts became a priority for the rebels. The owners and keepers of the majority of the manuscript libraries in the city, fully aware of the danger that threatened them, took urgent measures to smuggle the manuscripts out of Timbuktu and transport them to Bamako, more than 700 kilometres to the southwest. One of the principal organisers of the rescue operation was Dr Abdel Kader Haïdara, the director of the Mamma Haïdara Memorial Library (one of the largest in Timbuktu) and the Executive President of the NGO SAVAMA-DCI, an association of owners of Timbuktu manuscript collections devoted to the preservation of the written heritage of the city. Dr Abdel Kader Haïdara persuaded most of the owners of the manuscripts to delegate to him the responsibility for rescuing their collections.

Mass Exodus of the Manuscripts

The manuscripts were transported in stages, in order to minimise suspicion of the insurgents. Metal chests the size of a large suitcase, widely used in Africa for packing clothes, were the optimal containers for transportation. To avoid unwanted attention, two such chests were usually the maximum load carried by a single vehicle. Given that the final number of chests of different sizes transported to Bamako totalled about 2,400, the maximum average load (i.e. two chests per car) entailed approximately 1,200 single-car journeys. Before reaching a safe area where they could be loaded into automobiles, some manuscripts were carried out of the city on donkey carts or transported on canoes on the Niger River. The transportation itinerary was intricate and had to be regularly varied to make the mass exodus of the manuscripts less visible. Since the manuscripts were gathered from almost every significant Timbuktu library, the total number transported reached about 285,000 individual items. Understandably, this dramatic operation took a full eight months, from June 2012 to January 2013, to complete. Thanks to the urgent transfer of manuscript collections to Bamako and some other locations, at least 95% of the Timbuktu manuscripts were saved from destruction.

At the present time, the manuscripts are deposited in various locations around Bamako, still locked in the chests in which they arrived. The change of environment from the dry north to the humid south, and the inappropriate storage conditions constitute yet another threat to the survival of the manuscripts.

The evacuation operation and temporary provisions for storage in Bamako were supported by several foreign governments and organisations such as:

- the Prince Claus Fund, the Netherlands

- the Ford Foundation, USA

- the DOEN Foundation, the Netherlands

- the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands

- the Juma al-Majid Centre for Cultural Heritage of Dubai

- Lux-Dev, Luxembourg

- the German Federal Foreign Office

- the Gerda Henkel Foundation, Germany